The American Botanical Council (who neither I nor many of you had heard of before this week) are celebrating their 100th issue of their quarterly peer-reviewed journal “HerbalGram” (it says in this press release here) by publishing an article revealing the hitherto undecrypted herbal secrets of the Voynich Manuscript.

The two authors, Arthur O. Tucker Ph.D (“botanist, emeritus professor, and co-director of the Claude E. Phillips Herbarium at Delaware State University“) and Rexford H. Talbert (“a retired information technologist formerly employed by the US Department of Defense and NASA“) found themselves so inspired by the similarity between the plant drawn on the Voynich Manuscript’s f1v and xiuhamolli / xiuhhamolli “the soap plant depicted in the 1552 Codex Cruz-Badianus of Mexico [on f9r]” that they concluded that the Voynich Manuscript must not only be post-Columbus, but also post-Conquest Nueva España (i.e. after 1519-1521).

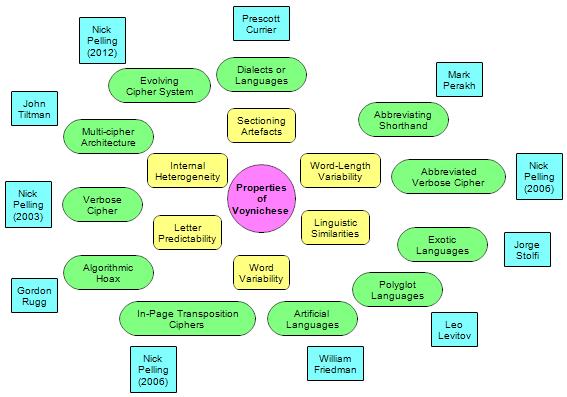

Voynichese, they believe, is therefore nothing more than a New World polyglot studded with “loan-words […] from Classical Nahuatl, Spanish, Taino, and Mixtec“, but which is overwhelmingly in an “extinct dialect, keeping much of the Voynich Manuscript’s secrets intact… for now.”

So… does this all reduce to nothing more than an “ethnobotanical cold case”; and if it does, have these two plucky independent authors actually cracked it? In the interests of open-mindedness and fair debate, you might want to flick through their paper for yourself here before you read the rest of my article dismissing their historical naivety and overhopeful botano-centricity.

What, you already think I’m being unfair to their abductive logic? For a start, if “abductive logic” isn’t a sixty-dollar term that means nothing much more than “generating hypotheses sufficient to explain observations” (and normally only a carefully-selected subset of observations to boot), I wasted my time studying logic at University.

I hate to start out by pointing out the ridiculously obvious here, but here in Voynich Research Land, we’re already up to our necks (and gasping for anguished breath) in plausible-sounding hypotheses that similarly seek to explain other carefully-selected observations. Selective abductivity is the disease, not the cure, and what they’ve done is terrifically selective.

The proper Intellectual History methodology (of which their methodology is the palest of shadows) is to take on board the sum-total of all the evidence across all the different analytical historical domains, and only then try to construct abductive hypotheses that explain the whole lot simultaneously. Here, the two authors found themselves driven towards a post-New Spain New World origin by a single apparently persuasive piece of evidence, and then rippled through the consequences of what that would have to mean for that portion of the rest of the evidence they allowed themselves to consider.

What they didn’t consider: the demonstrably 15th century vellum in play (radiocarbon dating), 15th century digit shapes (in the quiration), 15th century number forms (in the quiration), 15th century contractions (on the zodiac roundel hand) and 15th century parallel hatching (in several drawings). So, that’s evidence from the domains of codicology, palaeography, and Art History immediately consigned to their great big wastepaper basket of Not Examined Here Stuff.

However, the way that they bracket these multiple classes of evidence is to say “but such spurious claims [of pre-Rudolfine origins] have channelized scholars’ thinking and have not been particularly fruitful“. In fact, what has held back Voynich research most over recent decades is the set of spurious claims of post-Columbine origins (e.g. John Dee, Edward Kelley, Cardan grille hoaxes, sunflowers, etc), of which these authors’ paper is merely the most recent example. For when you bracket out evidence from multiple parallel research domains, you’re setting yourself up for a fall.

Another thing that annoyed me was that even though they tentatively identified Voynichese as Nahuatl, they nowhere mentioned John D. Comegys (twin brother of Cipher Mysteries regular James Comegys), who for years has championed a Nahuatl Voynich link. Even Kircher & Becker’s ridiculous book identified Voynich as a polyglot mess mix of “l’allemand, le suédois, le néerlandais, le latin, l’anglais, avec quelque notions de gaélique et de nahuatl“, and hence dated the object to “entre 1570 et 1610”. Hence it doesn’t seem to me that Tucker and Talbot even attempted any kind of literature review beyond a grudging scrollthrough of Wikipedia (ha!) and voynich.nu.

They also seem unaware of the light painter / heavy painter debate (i.e. they naively take it as read that all the paints the manuscript presents are original, despite the evidence to the contrary), and the bifolio reordering debate (i.e. they naively take it as read that the foliation is original, despite the evidence to the contrary). Oh, and they seem completely unaware of the post-1990 debate over the Voynich “sunflowers”, with their account starting and stopping with Hugh O’Neill in 1944.

They also bracket out the “medieval German script” on f116v (which they consistently mis-spell as “Michiton Olababas”) as a freestanding mystery, apparently unaware that Voynichese letters are embedded within both this and the marginalia at the top of f17r (which I found in 2006 with a UV blacklamp, but which were later photographed by the Austrian documentary makers in 2009).

Many other things annoyed me (their treatment of the Codex Osuna, the “maiorica”, etc, etc), but I’ve got to 850 words already and that’s more than enough annoyance for one post. But one last aside…

What I came to hate about the Voynich mailing list was that some time around 2006 it had subsumed the trendy-but-ghastly management meeting notion that “there’s no such thing as a bad idea” (usually said in a dippy, please-don’t-be-a-hater voice). Actually, if you have a whole array of basic physical evidence to work with, yes there definitely is such a thing as a bad idea. And the sooner people putting forward such bad ideas get to take their fingers out of their ears and stop saying la-la-la at all the thousands of pieces of ‘inconvenient evidence’ they’d rather bracket to tell their story, the sooner we’ll get to hear some good ideas instead.

In short, I would be delighted (and would indeed be the first to cheer) if Tucker and Talbot had put forward a good idea. But I think they have failed to do so in numerous different ways, all of which were easily avoidable.