Anyone trying to make sense of Charles Dellschau’s partly-enciphered airship drawings will quickly run into three roadblocks: (1) what was the mysterious “NB gas” that allegedly made the airships buoyant? (2) What was the curious green “soup” that was allegedly used to release additional NB gas whilst in flight? (3) What was the mysterious group “NYMZA”, whose enciphered initials appear on so many pages of Dellschau’s notebooks?

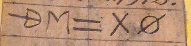

Here’s what “NYMZA” looks like in Dellschau’s cipher:

NB Gas

In terms of chemistry, there are very few substances that are less dense than air at normal air pressures and temperatures (and that can hence be used to lift an airship).

Of these, hydrogen is the best known, but it is prone to explosion; methane too is similarly prone to going bang; while helium was only properly isolated in 1895 (and so was not in play in 1856, the year when – according to Dellschau – Peter Mennis discovered “NB gas”), broadly similar to neon, krypton, argon etc.

However, there is one other “lifting gas” that was within reach of inventors circa 1850: ammonia. Even though ammonia is only half as dense as air (by way of comparison, hydrogen has 8% of the density of air, so an ammonia-filled balloon would need to be a fair bit bigger to get the same lift), and is stinky and noxious, it has many secondary benefits.

Interestingly, there’s a 2016 article by Brett Cohen (Karl Kluge kindly pointed this out to me, thanks Karl!), published in “Shadows of Your Mind” Vol. 1 #10, pp.78-81), that proposes that Peter Mennis’ NB gas was indeed ammonia.

It’s a good theory, certainly better than Jerry Decker’s somewhat forlorn theorification that Mennis may have found one of 26 elements supposedly missing from the periodic table before hydrogen. (*sigh*)

Even if we proceed by Holmesian elimination, ammonia seems a strong pick. And yet… it has to be pointed out that ammonia’s relatively meagre advantage over air as a lifting gas would probably have meant bigger balloon envelopes than the ones depicted by Dellschau. This is a tricky issue that everyone panning Dellschau’s notebooks for historical gold dust has to face up to.

All the same, I think it’s fair to say that ammonia is a very strong candidate for NB gas, with no obvious alternative contender (Dellschau repeats many times the idea that other gases were too explosive to be used in airships – and though ammonia is, ummm, slightly explosive, it’s still less troublesome than the others).

Suppe

The second problem is the “suppe” (which Dellschau always paints green): this is a liquid substance that get somehow poured onto a spiked ‘turner’ device, releasing the NB gas. At one point, Dellschau calls it “pys suppe” (which I believe means “pea soup”, though you will have to form your own opinion).

Want your airship to go up? Pour “suppe” onto your spike turner to release NB gas into your balloon envelope. Want your airship to go down? Release some NB gas from your balloon envelope. Whereas the most technically aware balloonists of the day were using ballonets (inflatable air bags inside the hydrogen gas bag), an ammonia-based airship need – theoretically – not use any such additional mechanism.

Cohen thinks that the two substances that were added together to release ammonia were were ammonium chloride (NH4Cl, A.K.A. sal ammoniac) and sodium hydroxide (NaOH, A.K.A lye, or caustic soda, first properly isolated by Sir Humphry Davy in 1807). The equation he points to is:

NH4Cl + NaOH –> NH3 (ammonia gas) + NaCl (sodium chloride) + H20

In Cohen’s concluding paragraph, he proposes “that ammonia gas (NH3) could be produced from a simple mixture of two solids, ammonium chloride (NH4Cl) and sodium hydroxide (NaOH) dissolved completely in water and allowed to react.”

Incidentally, ammonium chloride is used as a food additive under the title “E510”. If you’ve had “salty liquorice” in Northern Europe, you’ve probably eaten ammonium chloride.

Overall, Cohen’s account is sensible and rational: and yet it has to be said that neither ammonium choride nor sodium hydroxide has a green appearance. In Crenshaw’s book (p.89), Peter Mennis’ discovery of NB gas is phrased in terms of “searching for a better way to extract gold from quartz”, and an experiment that went wrong (in a good way), though Crenshaw doesn’t connect this explicitly with references to Dellschau’s notebooks.

Cohen may be right, or he may be wrong – it’s hard to tell. Even if Mennis’ NB gas is indeed ammonia, I think it’s hard to feel confident the “suppe” secret sauce has yet been figured out properly.

NYMZA

In many places, Dellschau alludes to what seems to be a shadowy group of investors who were at least partially bankrolling the inventors in the Sonora Aero Club: he calls the group “NYMZA” (but only ever writes its initials in cipher, as far as I can tell).

If NYMZA is an acronym, it’s certainly a curious one: though it’s hard not to read the first two letters as “New York” (arguably the investment capital of the world back then), the “MZA” part feels much more like a German acronym.

If the “M” is the first letter of a German word, I wondered if it might be (for example) “mechanisch or mechaniker”. Similarly, I wondered whether the “Z” might stand for “zunft” (guild), “zirkel” (circle), or “zeichner” (draftsman / designer). Finally, I wondered if the “A” might stand for “Assoziation”. However, my cunning websearches for all of these yielded plenty of false positives, but nothing actually helpful.

Yet Dellschau himself was born in Prussia in 1830, and his written language is a mishmash of English, German, French and sometimes apparently phonetic renderings. For example, I personally find it hard not to read all Dellschau’s transcriptions of “Moyk Gorée” and not to wonder whether the person’s name was simply “Mike Grey” (possibly from Britain or Ireland?).

In that context, it’s also quite hard for me to look at “NYMZA” and not wonder whether this was an imaginary Anglo-German group of investors that Dellschau had himself made up. In which case, the question is whether Dellschau had made it up in 1857 in California, or whether he made it up back in Houston many years later.

Your thoughts, Nick?

Though it would be nice to believe that NYMZA and Sonora Aero Club existed just as Dellschau’s notebooks imply, there currently seem to be more historical and technical impediments than supporting evidence.

To be fair, I can imagine that Californian miner Peter Mennis existed, and even that he indeed discovered a lifting “NB gas”; I can even imagine that Mennis may have been able to build a small test balloon using his NB gas, and excite other people’s imaginations.

Yet startup ventures throughout history have faced immense difficulties re-engineering a demonstrator into something that works at scale: and, so far, I don’t really see any way that the rest of the Sonora Aero Club (itself a name that wasn’t really possible until 1900 or so) was anything apart from a local Liar’s Club / drinking club formed to fantasize about manned flight amidst the brutal day-to-day madness of a Gold Rush.

But hopefully I’ll be proved wrong. 😉