I’ve just bee(n) reading Gene Kritsky’s “The Quest for the Perfect Hive”, which, though it covers many different sides of apiculture, ultimately focuses on the evolution of hive technology. This, of course, brought me back to thinking about the Voynich Manuscript’s ‘Bee Secrets’ page that I discussed briefly in The Curse of the Voynich.

Back then, I’d wondered whether the page (one of the panels on the reverse side of the nine-rosette page) might have been an enciphered version of Filarete’s book of secrets relating to bees (along with water, machines, agriculture, etc). And so I had discussed the drawings on this page with the tippitty top bee expert Dr Eva Crane (who I’m sad to say died in 2007): she pointed out that the hives apparently depicted there were conical skeps. This is a type of hive thought to have originated in Germany and which beekeepers south of the Alps almost never used (they instead used horizontal log hives).

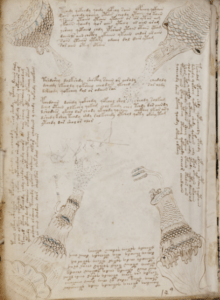

The Four Skeps

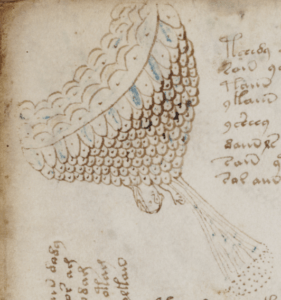

In the top left ‘skep’, the beekeeper might possibly be smoking the bees out of a hole in the top:

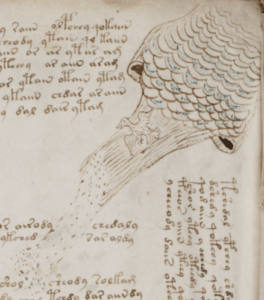

In the top right ‘skep’, we see a stylised bird (not sure what this represents) and bees going in or out of the bottom (this is one of those Voynich drawings where we seem to have an original layer and an obscuring layer on top, others like this are in Q13):

The bottom left skep is oddly stylised and apparently multi-stage, and it’s not clear what the beekeeper is doing (perhaps smoking the bees out?). The dots in the body, however, appear to be where the honey / honeycomb would be, so perhaps some kind of honey extraction mechanism is what is intended here:

Finally, the bottom right skep has the mysterious bird again, and again the inner (dotted) honeycomb seems to be exposed:

What Does It All Mean?

Oddly, Dr Crane’s observation hints that this single page might offer us a microcosm of the secret history of the Voynich Manuscript: a German bee-keeping technique, perhaps with a mechanical innovation added by the author, all concealed in plain sight, and being re-presented for an Italian audience. And this doesn’t necessarily have to have anything to do with Filarete (whose personal motto was the industrious bee) for it to be true.

What I learned from Gene Kritsky’s book (pp. 160 ff.) was that accounts of bee-keeping often included “bee calendars”, that told bee-keepers what to do in different months, zodiacal signs, or seasons. And I’m now wondering whether that accounts for the way the writing on this page appears in four directions, i.e. the four seasons of bee-keeping:

In terms of a block paradigm match, therefore, I currently believe the source material for this page will turn out to be an early (1380-1450) account of conical skeps written in Italian (or possibly Latin), derived from Northern European sources (probably German, possibly Swiss), and with four paragraphs corresponding to the four seasons of bee-keeping.

Some texts – courtesy of the ‘Medieval Bestiary’

https://bestiary.ca/beasts/beastsource260.htm

and I see you do not budge on the rosettes page. [smile emoticon]

Diane: some good texts there, but there are plenty more out there. I’m trying to bridge the gap between Pietro de’ Crescenzi (d.1320) and Girolamo Ruscelli (1538-1566) / Ulisse Aldrovandri (1522-1605) for my next post.

There’s a great-looking book on Italian Apiculture which doesn’t seem to be for sale or in libraries anywhere (literally zero copies in WorldCat, which is a bit unusual – I’m wondering whether they actually printed any).

Nick,

In depicting the man-made beehive, some medieval images employ a parallel wave pattern for the surface – echoing the steps of the natural hive, while others seem – at least to me – to mean to evoke the basket-woven pattern of the skep as e.g. British Library Royal 12 C XIX f. 45)

I look forward to seeing illustrations from the Italian works you mention.

D.N.O’Donovan: no doubting that the “stylised bird” in NP’s “four Skeps” be none other than the ellusive ‘greater honey guide’ (certainly looks like one), a native to Mozambique that has a quid pro quo deal with humans to locate hidden wild nests ripe for plunder. This be in turn for unwanted hive waste and help with mating. All fits with the time of Portuguese settlement of it’s first African colony (1506) and suits sans C14 miscreants having post 1432 Voynich Manuscript dating theories.

John – did you know that classical writers regarded the bee as a form of bird, or that in some sources used in medieval times, it wasn’t a queen bee but a king bee thought to rule the hive? Now you do. 🙂

…and then there was the “greater honey guide” and still is, a bird with feathers, beak and all. Sure don’t look like no honey bee to me, but it’s a tough call when you know stuff all.

Regarding this train of thought. The tiny dots in the “honeycomb” would more likely represent eggs. Any beekeeper looking at these illustrations would immediately come to that conclusion.

John,

if you do really do know someone who thinks the bird a species native to Mozambique, it seems they support Nick’s ‘hive’ theory – which is nice for him.

What they need to do then is to show how people drew things like birds and beehives in that region before 1440.

It’s not beyond all possibility, even if so very little remains from that earlier time – after all, the world beyond Europe was not uninhabited, or occupied by less intelligent people waiting for a ship-load of gold-mad, insanely arrogant, uncouth Portuguese to turn up.

It would be interesting to know if da Gama knew Idrisi’s geography, or had heard of Ibn Battuta’s travels – Battuta being another native-born North African, whose account of east Africa dates to the fourteenth century.

https://sacredfootsteps.com/2023/07/03/ibn-battuta-in-east-africa/

yeah, yeah… I get the symbiosis thing.

Nick,

You might want to check your sources for the statement that skeps were invented in Germany.

I’ve been looking around for a timeline of skeps and how they are represented in art. On one site I found the following…

“the first structured beehives emerged later in ancient Greece and Rome in the form of skeps. Skeps were typically made from coiled straw or wicker, resembling a domed basket with an entrance for the bees. These simple yet effective structures allowed beekeepers to manage colonies and extract honey, although their design lacked the ease of modern hive inspection.

In Northern Europe, log hives were prevalent during the medieval period. These hives were hollowed-out logs with a small entrance hole, providing natural insulation and protection for bees in harsh climates. Log hives remained popular for centuries due to their durability and suitability for cold weather conditions.

It’s from an article written mid-2024 and updated in Dec.2024 – for the ‘Planet Bee Foundation’.

https://www.planetbee.org/post/evolution-of-beehives-a-journey-through-time

In terracotta, to be used as a coin-bank, a Roman artefact in that form, dated 2nd-3rdC AD. (not sure why the museum classed it as something for children)

https://archaeologicalmuseum.jhu.edu/class-projects/archaeology-of-daily-life/childhood/beehive-savings-bank/

Plenty of evidence for skeps – not any for drawing them like the Voynich folio so far.

The 10th century Geoponika, a twenty book compilation of agricultural lore, contained a section on apiculture. it was compiled for the Byzantine Emperor Constantine VII.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Geoponica

Go to the bottom of the page and click on Translation by Thomas Owen – see from p 226 onwards for a discussion of both the practical aspects of beekeeping and the religious and symbolic importance of the bee. The bee is seen as an organised and wise animal that is a shining example to humans, and their society reflects God’s order.

“The bee is the wisest and cleverest of all animals and the closest to man in intelligence; its work is truly divine and of the greatest use to mankind. Its social life resembles that of the best regulated cities. In their excursions bees follow a leader and obey instructions. They bring back sticky secretions from flowers and trees and spread them like ointment on their floors and doorways. Some are employed in making honey and some in other tasks. The bee is extremely clean, settling on nothing that is bad-smelling or impure; it is not greedy; it will not approach flesh or blood or fat but only things of sweet flavour. It does not spoil the work of others, but fiercely defends its own work against those who try to spoil it. Aware of its own weakness, it makes the entrance to its home narrow and winding, so that those entering in large numbers to do harm are easily destroyed by the guardian bees.

This animal is pleased by a good tune: when they are scattered, therefore, beekeepers clash cymbals or clap their hands rhythmically to bring them home. This is the only animal that looks for a leader to take care of the whole community: it always honours its king, follows him enthusiastically wherever he goes, supports him when he is exhausted, carries him and keeps him safe when he cannot fly. It particularly hates laziness; bees unite to kill the ones who do no work and use up others’ production. Its mechanical skill and near-logical understanding is shown by the fact that it makes hexagonal cells to store honey.”

On the hives it states:

“The best hives, that is, containers for the swarms, are made from beechwood boards, or from fig, or equally from pine or Valonia oak; these should be one cubit wide and two cubits long, and rubbed on the outside with a kneaded mixture of ash and cow dung so that they are less likely to rot. They should be ventilated obliquely so that the wind, blowing gently, will dry and cool whatever is cobwebby and mouldy…”

It also discusses the seasonal care of bees:

“As food for young bees put out wine mixed with honey, in basins, and in these place leaves of many-flowered savory so that they do not drown. To feed your swarms in the best possible way whenever they stay at home because of wintry weather or burning heat and run out of food, pound together raisins and savory finely and give them this with barley cakes. When the first ten days of spring are past, drive them out to their pastures with the smoke of dried cow-dung, then clean and sweep out their hives: the bad smell of the dung disturbs them, but cobwebs are an obstacle to them. If there are many combs in the hives, take away the worst, so that they are not made unhealthy by overcrowding.”

People still underestimate the importance of Byzantium and the Macedonian Renaissance to the later Italian Renaissance.

Bees were often thought to have originated in Paradise and were seen as symbolising chastity.

https://historyofbees.weebly.com/bees-and-catholicism.html

https://buzzingaboutbees.com/bees-symbolize/

There are some medieval depictions of birds and bees here:

https://blogs.bl.uk/digitisedmanuscripts/2019/08/the-birds-and-the-bees.html

The worker bee is also the symbol of Manchester (a hive of industry) and indeed the most famous Manchester beer Boddingtons (the brewery is now closed) used the bee on its logo. I saw the legendary “icon” Nico supping a couple of pints of Boddies after her performance at Manchester’s Band on the Wall.

https://uk.pinterest.com/pin/pinterest–404831453981409837/

https://www.manchestersfinest.com/articles/symbol-city-manchester-bee/

Folks who want the real buzz on bee hive secrets and how the Mozambiquees found them in the forest in the days pre Vasco da Gama and still, you’ll find it all laid out and readable in Wikipedia under ‘Greater Honeyguide’, a member of the passerine (woodpecker) family. No need to post further detail in my own words that would only bore you all shitless, eh Nick, Diane, Syph?

Diane: yes, skeps themselves are ancient, but the history of their use is not as straightforward as the page you linked to suggests. I’m revisiting the history now, trying to build up a clearer picture…

I could have swarm that my bee seeking ‘greater honeyguide’ be a cookoo but alas, seems it be related to the woodpecker in its looks, treed habitat and by nature it be quite vocal, territorial and inclination to be a loner unless seeking a a bit of fluff. Such being the case stands to reason why only single birds appear in Nick’s breath of fresh air ‘Bee Secrets’ page. If my input be taken seriously (a first) this could result in a need to rethink acceptance of the 2009 (no official report) carbon dating 1404/38. That’s half a century before the Vasco da Gama sailed from Lisbon on a voyage of discovery to Africa and beyond. Wonder who was it came up with ‘the bird is the word’, maybe it was Wilfrid Voynich, Heaven forbid if he did.

Steve H.,

If you want to get your teeth into an interesting question, try ‘What relationship might there be between the Roman bucolic and agricultural texts, the now-lost work of Mago, and the Geopontica?’ Should keep you busy for a while. Then you can move up to the question of the degree to which the ‘Arab agricultural revolution’ theory is (a) well-based and (b) relevant.

😀

Probably doesn’t need saying that skeps similar to those in VM are typical of those produced by natives of Mozambique from the onset of early hunting and gathering collectives. They were made in the hundreds and distributed haphazardly around forests they inhabited and even further afield depending on which flowering trees were attractive to wild bee populations thereabouts, hence harvesting would have been more arduous. Even moreso and time consuming, that being without a little help from their feathered friend, the greater honeyguide.

In case anyone is interested.

The bee most commonly kept in the Middle Ages was the Apis mellifera mellifera. Also called the alpine bee.

It is European, peace-loving and hardy. At 25 million years old, it is one of the original bees.

https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dunkle_Europ%C3%A4ische_Biene#:~:text=Die%20Dunkle%20Europ%C3%A4ische%20Honigbiene%20(Apis,und%20der%20Urtyp%20aller%20Honigbienen.

Maybe someone will be interested. But the folio says nothing about bees. And it says nothing about beehives either. Of course it says something about a bird. But it is not a bee eater and it is not a predator either. Eliška z Rožmberk writes about sub. (SUP is a bird) Substitution. At the top right, it will show you the substitution of the number 3 again. And the text says: I am throwing away the code. They are small dots. (it looks like ashes are being scattered). The translator cannot translate the Czech word ” s.y.p.u. “. So in Czech it is written ” S.y.p.u. c.o.d.

Peter M.

Only 100 million years out with your not so original peace loving, Euro bee, tree puller.

Nick,

I think the author of that ‘Planet Bee’ page assumed that a ‘bole’ must refer to a tree… hence logs.. but that isn’t necessarily so. A ‘bee-bole’ was a structure, a wall, or a building, which contained a number of alcoves or niches, into each of which a skep could be placed.

I expect you know this already, but some of your readers maybe interested.

I don’t want to be a spoil-sport, but the Voynich drawing’s tower-like structures present a problem, especially when there’s nothing in the drawing unmistakeably bee-shaped, and nothing with the skep’s characteristic bell-shape, so to maintain the ‘bee’ theory here, I’m guessing those towering forms would have to be argued description of some natural habitat or – perhaps – bee-towers, if there was such a tradition in Europe or anywhere else.

Nick’s theory is a theory about the intention behind a certain drawing, so before taking the interpretation as a given, and to avoid its being shot down, I think Nick’s reading of it needs to be provided more art-historical grounding.

I’ll be keeping an eye open for anything that might help.

Then of course you have your ‘scaley throated honeyguide’ nest thief bird that got into the ‘quid pro quo’ act early in the anals of homo/anthophila co-existance by engaging with stone age Hanza hunter gatherers of Northern Tanzania for to locate wild bee hives and share in the spoils, though not always equally. Pity it couldn’t have been C. Friedman’s (not William the crypto) falso honeyguide out of Monza in North Eastern Italy

I agree with Diane.

I also don’t think the site has anything to do with bees or beekeeping in any sense.

I think it’s more about nutrition. The dispute between humans and nature over resources.

This would be a topic that is not visible in the VM, but appears in other books.

@John Sanders

With the 100 million years you are talking about wild bees in general.

However, these are not state-forming honey bees but solitary bees.

But we are talking about honey bees and keeping them

How are things in Glocca Morra?

Yep, I’m a little skep-tical (ho! ho!) about the birds and the bees myself. Specially the bees. The third and fourth “skeps” look more like plants to me, maybe releasing pollen. And the little feller in picture three appears to be naked which might not be advisable when handling our apian friends. A sting in the tail would be the least of it.

Veg has obviously fallen for it. No, a cat hasn’t bitten my tongue soldier. but I’m beginning to be a bit of a star on Reddit after a shaky start, regaling all the trendy young things with tales of my adventures seeing all those cool bands back in Manchester in the ’80s and going to the hippest and now legendary clubs and venues. Green with envy they are, especially the Yanks, and I don’t blame ’em. I’ll have to find somewhere to tell all my yarns about my travels and travails in the Outback cos the young people love Australia, God bless ’em. When they find out about my brushes with man-eating crocs and near misses with crazy truckers and knife wielding psychos, let alone my encounter with supernatural entities in Arnhem Land, they’ll be swooning. And I’ve had 138K views of my forensic analysis of the Henry McCabe voicemail although it’s still only 93% positive on the upvotes. Feel free to visit and give it a thumbs up pal.

And Diane, the only Mago I know anything about is the “magickal” island of Tago Mago off the coast of Ibiza, near where I holidayed with the rellies in 1975. Supposedly associated with Aleister Crowley, the islet also gave its name to my favourite album of all time, Can’s Tago Mago.

I have now thought again about the symbolism of the drawings.

After 2 beers I realised that they might be signs of the origin.

That’s how I see it in religion, origin from heaven, or even Quire 13, as origin, or origin from the previous.

Enlightenment thanks to per mille. o/oo. (promille)

Fucking translator.

This has more detailed info on beekeeping than most sites and a bibliography:

https://www.annualreviews.org/content/journals/10.1146/annurev-ento-031616-035115#right-ref-B55

If the naked bloke is doing summat with bees maybe he is uttering a swarm charm and throwing dirt over the little bastards.

“Although it was discovered copied into the margins of an 11th-century manuscript, “For a Swarm of Bees” is believed to be older, from the ninth century. It’s one of the earliest examples of a subset of metrical charms called “swarm charms.” These were magic spells once used by beekeepers across Europe to control and direct their precious honeybees and prevent them from flying off when they gathered into a swarm. “For a Swarm of Bees” begins with physical instructions and ends with what you should say to the bees:

“Take [some] earth, throw it with your right hand under your right foot, and say:

‘I catch it under foot, I have found it. Lo! Earth has power against all and every being, and against malice and against mindlessness, and against the mighty tongue of man.’

And then throw dust over the bees when they swarm, and say: ‘Sit you, victory-women, settle to earth! Never must you fly wild to the wood. Be you as mindful of my welfare as each man is of his food and home.’”

Tossing dirt over the bees would have been just as important as the magic words; perhaps more important, since it would have produced the desired result of getting the confused insects to settle on the ground en masse. The bees are addressed as “victory-women” (sigewif, in Old English) because this term was also used for Valkyries and warrior women, and like them, worker bees are females who wield a “sword” (their stinger). Other swarm charms gave the insects pet names like “little animals,” “beauties,” or “dear ones,” in languages from German to French to Greek. Though most examples come from the Medieval era, swarm charms persisted until as recently as the 19th century, when changes in beekeeping made them obsolete.”

https://www.atlasobscura.com/articles/swarm-charms

Peter M: what kind of ancient bee keepers you bee referring to? Not too many human erectus homo sapiens trapsing around the Alps tending to their friendly Apis mellifera mellifera bees and harvesting their honey from skeps 25 million years ago, far as I’m aware

Syph : The birds, the bees and the Portuguese if you please, and if’n you don’t please, there’s always Peter M’s Swiss cheese with holes all through it and hints of Apis mellifera squared.

Mind games and/or musing had me thinking how much alike in shape and form is the hive skep top left with your common everday lotus pod. I put it to the test with Google and first thing comes up, yep you guessed it, comparison photos of a green lotus seed pod cluster beside a honeycomb, images denoting a visually tantalising trypophobic stimuli (whatever that may bee), much like Maggie Boole intended no doubt.

We’ll try to sound neutral, but the truth is often very bitter. Cryptography is a natural science. It’s a sister of computer science, mathematics, statistics… There’s a mountain of literature out there to determine whether it’s for someone or not. You can find out very easily. If you don’t want to buy nonfiction books, go to my site (before I take it down in the next few weeks,because the Host frequently switches off the SSL certificate), download the articles on theoretical computer science—how Constaint Satisfaction can be used for decoding, or the theoretical discussion of complexity classes, incompleteness proofs, etc. If you can’t follow these articles, then cryptography isn’t the discipline for you. All that’s left is buzzing around with bees in hives or juggling with obstetric instruments or spindles…

Just to occupy a few idle moments I have been considering the importance of the mid 15th century Venetian Roccabonella Herbal. As stated by Sarah Kyle:

“The illustrated herbarius…of Venetian physician Nicolò Roccabonella (1386-1459) remains mysterious in part because of what he calls its “more modern order”, the significance of which has been unexplored in modern scholarship. Created by Roccabonella and the Venetian painter Andrea Amadio (fl. 15th cent.) in the mid-fifteenth century, penned in ink predominantly on paper, and illustrated in watercolour, the Roccabonella Herbal contains 458 chapters on individual plants used for medicinal purposes. While the general organisation of each chapter (image on one side of the folio and text in two columns on the other) and its subject matter (medicinal plants) remain consistent throughout the manuscript, the textual and visual contents of the codex, to my knowledge, do not consistently conform to any recognisable or traditional system of classification or organisation. Both the textual and visual content of Roccabonella’s book confront the reader with the uncanny feeling of engaging with different systems or parts of systems – from multiple times and places – simultaneously.”

https://www.academia.edu/104334207/A_More_Modern_Order_Virtual_Collaboration_in_the_Roccabonella_Herbal

An epistemological conundrum to ponder over maybe? I was reminded of the Earl of Pelling’s admiration for Michel Foucault’s work and, although I haven’t read it for many years, Foucault’s classic The Order Of Things. I’ve still got my copy so I’ll have to get it down one day. Meanwhile I’ll have to quote from Wikipedia:

“The Order of Things: An Archaeology of the Human Sciences (Les Mots et les Choses: Une archéologie des sciences humaines) is a book by French philosopher Michel Foucault. It proposes that every historical period has underlying epistemic assumptions, ways of thinking, which determine what is truth and what is acceptable discourse about a subject, by delineating the origins of biology, economics, and linguistics….

In The Order of Things: An Archaeology of the Human Sciences Foucault wrote that a historical period is characterized by epistemes — ways of thinking about truth and about discourse — which are common to the fields of knowledge, and determine what ideas it is possible to conceptualize and what ideas it is acceptable to affirm as true. That the acceptable ideas change and develop in the course of time, manifested as paradigm shifts of intellectualism, for instance between the “Classical Age” and “Modernity” (from Kant onwards) — which is the period considered by Foucault in the book — is support for the thesis that every historical period has underlying epistemic assumptions, ways of thinking that determined what is truth and what is rationally acceptable.

Concerning language: from general grammar to linguistics

Concerning living organisms: from natural history to biology

Concerning money: from the science of wealth to economics

Foucault analyzes three epistemes:

1 The episteme of the Renaissance, characterized by resemblance and similitude

2 The episteme of the Classical era, characterized by representation and ordering, identity and difference, as categorization and taxonomy

3 The episteme of the Modern era, the character of which is the subject of the book”

Dissect and discuss!

@Sanders

I have no idea what you want to achieve with your slogans.

But please,

Beekeeping dates back to 3000 BC.

Heidelberg and the Neander Valley are on the northern edge of the Alps.

Hence Neidelbernemsis and the Neanderthals.

https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Homo_heidelbergensis

https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Neandertaler

The honey harvest is even depicted in cave drawings.

https://www.zeidelmuseum.de/zeidler-damals/

And no, the Telettubbies are not the survivors of the UFO crash from Rosswell.

Perhaps that fills in the gaps in your education, hence the symbolic holes in Swiss cheese.

https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Teletubbies

From a psychological point of view: You still haven’t digested the fact that your VM theory simply doesn’t work. Escaping into Somerton self-talk won’t help.

What you need is real help.

Translated with DeepL.com (free version)

Here you can see the cave drawing of the honey harvest better.

https://aceitecsb.com/de/die-bienen-ihr-honig-und-ihre-kuriositaten/

DM: I can’t get my ancient device to pick up on your Manus AI top notch input as expected, but my understanding bee that the first line of the Tamam Shud code offers a more direct route of train travel between starting point than the last line, ie., the long saught after Holy Grail Bee line to the honey pot. Congratulations.

Veg

You changed your tune pretty quick. I did notice a similar pair of “lotus pods” at the top of one of the balneological illustrations, the one with the odd tubes. I found a recent article which you won’t be able to read cos you’re chicken that includes the following:

“Most striking of all were the groups of naked women. They held stars on strings, like balloons, or stood in green pools fed by trickling ducts and by pipes that looked like fallopian tubes. Many of the women, arms outstretched, seemed less to be bathing than working, as plumbers in some primordial waterworks.”

https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2024/09/decoding-voynich-manuscript/679157/

It’s all about Lisa Fagin Davis – “Annie Oakley” – but don’t tell Nick cos she’s presumably a rival! She’s into Elvish, and that’s not a drunkards way of pronouncing the King’s name.

Talking about rock’n’roll you’ll be pleased to know that I’m beginning to get responses to my posts and comments on Reddit from some very well known and well respected musicians. They love my tales!

I thought of you when I read some of Davis’ comments:

“Her frustrations boiled over in an August 2019 op-ed she wrote for The Washington Post. “We watch ‘Game of Thrones,’ we read ‘Lord of the Rings,’ we play medieval-themed video games, and therefore we think we know something about the Middle Ages,” she wrote. The fantasies that pass for medieval history in popular culture had come for the Voynich, fueling media coverage of shoddy research and “turning an authentic and fascinating medieval manuscript into a caricature of itself.”

But after a couple of years, Davis developed second thoughts about her social-media smackdowns. It was less the hate mail she got from “Voynich bros,” as she called the men who dominated online forums—though that didn’t help. She’d just begun to feel unkind, as though she were punching down at people genuinely inspired by the manuscript’s mysteries. Hadn’t she once been one of them?”

I didn’t know William Friedkin had had a go at solving the Voynich puzzle. Maybe he had a French Connection or maybe he called in an Exorcist to eliminate the Curse of the Voynich.

A form of tower-hive – this reference very late. Perhaps a seventeenth century invention. Perhaps, as so often, an invention copying what an author found as some traditional regional custom.

“John Gedde described a storified/tiered wooden hive with an octagonal shape in his book first published in 1675.”

viz. John Gedde, ‘The English Apiary… ‘ the book includes plans to scale and is available as a pdf, linked in footnote 1, on the website I’ve quoted.

https://warre.biobees.com/hexagon.htm

It appears that in Europe, the sex of the queen-bee wasn’t “discovered” until 1586, and in England as late as 1678, though possibly as courtly politeness, the bee-master to Charles II, Moses Rusden, still refers to ‘king-bee’ in his *A Further discovery of bees..*

I mention Rusden’s book because it too shows an image of an hexagonal tower hive, an image in this case surmounted by a crown and elaborate coat of arms.

PS – a copy of that image can be had from Alamy. Code – RM ID T96K79

Andrew Gough’s bee-related musings – mostly historico-cultural – are still online. Among his well-chosen illustrations is the photo of a true ‘log beehive’ in Lithuania.

https://andrewgough.co.uk/articles_bee2/

Darius: Now that you mention it, I’m more than content to dabble with obstetric instruments such as the pelvimeter developed in the 18th century for a specific purpose by likes of surgical inventors Smelley and Baudelocque. I don’t consider the spindle to have been an invention as such, merely a simple revolving device having variable design features that could be utilised to shortcut a host of uniquely complex mechanical procedures; Something like theoretical computation devices used to good effect by geeks in the simple science of cryptology I expect.

Bee dance here:

https://fr.pinterest.com/pin/559853797405877923/

Same gesture as the little fellers in the Four Skeps (to heaven?) illustration in the Voynich Manuscript. What a buzz!

Loads more images of skeps:

https://fr.pinterest.com/boryssnorc/medieval-bees/

I’ll bee off now!

Honey bees prefer Aboriginal art to Monet:

https://theconversation.com/bees-can-learn-the-difference-between-european-and-australian-indigenous-art-styles-in-a-single-afternoon-110494

See also:

https://nativebees.com.au/indigenous-significance/#page-content

https://www.anba.org.au/news/the-birds-and-the-bees-and-aboriginal-culture/

Bee Representations in Human Art and Culture through the Ages:

https://brill.com/view/journals/artp/10/1/article-p1_2.xml

I really will buzz off now!

Syph: why not take your hairy arsed honeyguide with you and fade off for skeeps.

Nick

I am calling on you, as a fellow patriotic Brit, to impose immediate tariffs on imported comments, starting with those coming from Australia and the Socialist Republic of Vietnam. The latter are particularly cheap, shoddy, based on slave labour – I’m sure the contributor in question has the “little woman” running around all day doing all the work while he sits on a commode with his underdaks round his ankles spewing out all his bilious nonsense – and fall apart on even the most cursory inspection. They usually appear to consist of nothing but hot air.

I would suggest charging $2 per comment published coming from Australia and a whacking 500,000 đồngs on those from Vietnam.

It is high time to Make Cipher Mysteries Great Again! We are perfectly capable of producing our own insults, putdowns and ad hominem rants. We are a creative, industrious and resourceful people. Stuff the rest the world. It is up to us to pull up the drawbridges and slag each other off in peace without interruptions from the likes of Vegetable Man.

Our “friend” from Indochina who has dominated this forum for far too long cannot object in any way. As a massive fan of Trump, Vance and Muskie Muskrat I am sure he would agree that each nation needs to look after its own interests, and in closing I can only tell him to take his miserable comments to China, just like his country’s manufacturers will have to start offloading all those trainers and smartphones to the same place. Goodbye Veg and good riddance.

Syph seems to have gotten her wires crossed, Trump’s fan base does not extend to the Socialist Republic of Vietnam, Cambodia or the chaos in Laos. Why should it when he and his running dog mates, Elon-gate and dead eyes Vance have just slapped a wopping 36 % tariff on our US high demand tradegoods including, Durians, raw Vinamin prawns, farm barramundi, robusta coffee dregs and UXBs (unexploded ordinance). Suggest she gets her fecking facts straight before she runs her toothless great ‘north’n south’ off.

No doubting the audacity of some folk. Take our feckless Ms. Horewood; she’s on again off again like a strumpet’s night attire, snitch keeps crawling back, just as a mongrel curr is drawn unerringly into the scent of its own stinking vomit.

Before Syph leaves the room hope she turns the light off. One small thing that Trump forgot to factor in with his mean spirited 36% import tarrif on his former unbeatable foe’s mostly American owned companies’ crumby trade goods. What pales this potential ill gotten return into insignificance be one commodity that Vietnam has which isn’t subject to taxing and which it guards jealously against take over by the gready powers China in particular. Any country now and into the future who has ambitions of gaining control of the world’s undeniably busiest sea lane can’t do so without having a powerful naval presence firmly imbeded in the former American east china seaport of Cam Ranh Bay. The eager contenders competing for a long term lease be USA, P/R China, Russia, India and the ever hungry Saudis waiting for a slice of the pie. All willing to give up anything including its beliefs to win the big prize, with Vietnam holding the ace card. Trump and his unstable mate Elon-gate Muskovite? might do well to watch their asses when attempting to do deals with the Hanoi mob (they read Donald duck). PS Liberation Day for Vietnam occurred fifty years ago this month, so with Trump having just declared America’s they have a bit to catch up.

“Good bye Veg and good riddance” piognant though hackneyed parting words I must say Syph. Could have done with an equally dull post script like “Mark my words”. My response to such kindness being “So long its been good to blow you” PS Take AT’s advice Syph and continue the treatment with wonder drug penicilin. Worked for my periodontitis.

…penicillin has proven to be doubly effective I’m told.

Veg

You still here? Are you forking out your đồngs or hasn’t Sir Nicholas of Pelling taken my advice? You sure changed your mind on Muskie – he was your hero five minutes ago. Looks like you’ve learnt how to use the spellchecker too.

Your apoplectic rants against moi have reminded me of a piece I found in an old student magazine (Gremlin) from my alma mater, the University of Kent at Canterbury. Back in June ’78 a mate and I saw a few punk bands on campus at the annual Keynestock Festival. Keynes was one of the colleges and we had a great time watching Alternative TV (‘Love Lies Limp’) perform in front of the duck pond there. Most of the students were longhairs and turned up their noses at the “new wave”. The MC was very sniffy about ATV so as soon as their set was over we left to see some local kids playing punk not very proficiently inside the college.

I had to laugh when I found a review of the festival cos the student author, who had a punk band himself and later became famous as poet/musician Attila the Stockbroker, described the “vast majority of the audience” as “apathetic Syphilised Zomboid wankers” and said that “the vast majority of student creeps in this hole…want to sit in their rooms and listen to ABBA”.

Funnily enough I made a post to a Canterbury Memories FB page recently laughing about the review (which I linked) amongst some other anecdotes about my time at UKC and one of the people who gave it a like was Attila the Stockbroker himself!

So I’m not a Syphilised Zomboid wanker I’m afraid Veg, as per the great man Attila.

‘Farageland’ to the tune of the Clash’s ‘Garageland’:

https://youtu.be/KgtgGv8pKHc?si=Vl7_ZiXGLM3cYmJh

The words “He’s about as welcome as an ice cream made of shite” might apply to yer bad self sport.

“A guy (gal) goes nuts if he (she) ain’t got nobody (to harass) talk with.” Can you guess where that quote came from Syph? might well have been from your own bitter lips.

Syph: only one reason I can think of as to why Lord Pomfret retains uneducated creeps like moi on the payroll, be to keep uncouth even less learned despicable, disturbing elements in check. Seems to have had some limited success but, you can’t kill with kindness much to my chagrin. Reckon it’s about high time I earned my keep.

“You sure have changed your mind about Muskie – he was your hero five minutes ago.” Really Syph, I don’t recall saying anything supportive about the man, nor do my backers or CM Admin for that matter. Perhaps one of us be mistaken. Not you surely, you’re not known for telling porkies.

Veg

My last comment on this matter. His Lordship must be pulling his hair out at this hijacking of the comments section re his post on the VM “bee secrets page” in the pursuit of a personal vendetta.

Over on Tbt (‘Steve H clears a few things up’ thread):

john sanders #

Reference y’man’s [moi] big putdown of Elon Musk. Man’s got three digits and nine zeros in the bank because he’s one cool mofo. On the contrary Steve H has his fingers in every pie and a zero with an X atop ala the TS code, indication of his dim wit and a total lack of decorum.

February 4, 2025

Syph: so what? if I did call Elon Musk ‘one cool mofo’ on another blog Doesn’t make the autistic chainsaw weilding lunatic my hero….mofo!

Syph: “truly a moron” be what aspie Elon gate openly thinks of the Don’s top trade adviser Peter Navarro’s tariff deal. Not such a mofo after all, could even get to like the sombitch.

I don’t agree with you on what this page consists of of, what is it. bees now? I had another idea about it than you about what it consists of. you can solve it Nick, then do so. This idea of “directing” the nature of the study I have never cottoned to.

Overall I think more clarity should be placed on how it arrived at the Vatican’s where it was when it went through the process. Once this is adequately determined then things like working on a solution can be worked on. As a video about it Inrecently saw mentioned “The jesuits aren’t saying…” Tell me about it.

Matt,

Nick’s post says nothing about “directing the nature of the study” so I’m puzzled – care to explain?

PS – as far as I know, the Vms was never in the Vatican library, if that’s what you mean. There was some speculation on the point a while ago, but it seems to have been quietly dropped.

Diane,

Semantics, ok? The manuscript was a part of the Vatican “system yes? If it wasn’t in the library itself, it was in the Collegio Romano, or the Jesuits had it somewhere.Then there’s the fact it came from RUdolfs court in Prague(somewhere) which was very much a Catholic institution. The possibilities are endless if you consider the go between of the Jesuits to Prague to look after suspected “charlatans” like John Dee. No one convered themselves in glory with Dee situation quite obviously. I have thought very much over whether the Ms could have emerged from this tumult, though Irealize it is currently a less than popular opinion, and one that I refuse to keep quiet about unless and until there is more clarity on it. Rene’s website is ok, but hasn’t produced this clarity for me yet.As forNick , what movie had a male character telling a female about another male “ae you his tongue?” If Nick has a problem with what I said, he can tell me himself right? So, on this please butt out, thanks!

Matt- no, actually that whole scenario was hypothetical. There are no records anywhere to tell us what happened to the manuscript after (as we suppose) Kircher received it. Voynich believed it must have gone to one of Italy’s noble families- I daresay he knew why. The evidence is that it came – possibly, not certainly came ‘back’ with other manuscripts after Fr. Beckx’ years in Fiesole. Some of them (not the Vms, apparently) then went into some section of the library and later the librarian was surprised that the Vms wasn’t there/among them when asked about it. The obvious question would then have been ‘have you a catalogue description for it? but oddly enough no-one seems to have asked that question, not the librarian or the person who enquired and was in the process of compiling a catalogue. No-one has *ever* asked, it seems – not then and not later. No paper trail for it at all apart from that earlier speculation I mentioned – based on a list of books in which nothing recognisably like the Vms is present. So if you want to stick to the facts, the ms’ history after c.1666 is “sent to Kircher” [gap of 245 years or so] “is seen among other manuscripts, including former possessions of Italian nobles, in a trunk which had been Fr. Beckx’ when he came to Rome after exile in Fiesole during the 1880s”. Imagination alone is responsible for ‘theory-patches’ – there’s no evidence it was ever in the library at Mondragone, not even after Beckx’ return to Rome. (see the full bibiography in my page at voynichrevisionist for details of those last months of his life.

Dee is another flight of imagination – no evidence Dee ever saw the ms. In fact, we don’t know from what direction the ‘bearer’ came who – according to none but Mnishovsky – brought it from England.

You have misunderstood, also, who was asking you what you meant when you spoke about ““directing the nature of the study” – who do you think is directing the study? I’m genuinely interested in your perceptions on the point and since nothing in Nick’s post offer a glimpse of it, I asked you to explain the phrase.

Diane,

Well the “system” lost it somehow, and I can only add that the Vatican Librarian gave every indication in Kraus’s book he thought that they still had it in stock. Why is that?

I will give you forewarning, I am one of those students who like RichnSanta Coloma

who think a hoax by Voynich is not out of the range of possibility. I will entertain reasons you think it impossible, though I will keep my research to myself. One thing I noticed though is that on the Voynich Ninja there was a message from Lisa Davis asking for a review of a new book about a possible hoax. Why would she ask this if there was a possibility, infintisemal as is it is? After all these years, the mysterious VMs, still atotal mystery.

Matt,

I have a lot of time for Rich and am glad to know that he’s not quite alone in the Voynich world.

Nick,

apropos of your Block Paradigm scheme of attack I noted that Opus Agriculturae by Palladius deals with several subjects that seem to be covered in the Voynich manuscript. Namely balnea and related subjects, bees and beekeeping, caves, agriculture and the seasons.

I think this grouping of subjects is unusual so I wonder if the Voynich was broadly modelled on Opus Agriculturae.

Byron: Palladius’ influence on medieval agricultural thinking can be seen through books such as Pietro de’ Crescenzi’s book and others, so in principle I agree with you. Palladius’ book was in turn based on the De re rustica of Columella, so there’s a whole tree of references going on here, including Albertus Magnus.

For ground truthing, I should really include Pietro’s comments on bees, to give a picture of North Italian apiculture circa 1304-1309.

The drawing on the top right looks more like water flowing through a canal and cascading down to the middle of the paper 🙂 The waves are painted blue, like water. The bird is flying in front of the waterfall.

Dear Nick:

What exactly did Dr Eva Crane mean when she pointed out that ‘the hives apparently depicted there were conical skeps’. Did ‘apparent’ mean ‘clearly visible’ or did it indicate doubt? If the latter, how much?

Some observations:

• The page layout indicates the drawings and text are probably about the same subject.

• The most distinctive symbols for beekeeping are a worker bee and the hexagonal comb. Neither appear in the drawings.

• There are several species of bee eating birds in Europe. The aptly named bee-eater is native to both Italy and southern Germany.

• The illustrations may show the process of removing comb from a skep hive. (You need to destroy the colony in order harvest a skep hive.)

Upper left: smoke them.

Upper right: Turn the hive over. The bees will come out. Invite a bee-eater to lunch.

Bottom right: Squeeze the contents of the skep basket into a sack. The bee-eater rests on a tree nearby, quite full after a heavy meal.

Not pictured: leave the sack in a cold place for a few nights in order to kill the remaining bees.

Bottom left: Remove the contents of the sack. The dots in the scalloped lines represent brood, while the taller arches represent honeycomb. Some bees will still be alive, and you will need to ward them off.

• Any repeated phrases throughout the text might deal with self protection. Something like ‘Run like hell’.

Disclosure: We have moderate confidence in our first guess, but low confidence in the last two.

@Nick

I know today is Karlfriday.

But what does it have to do with robinson crusoe?

Nick,

I’m sure you know my opinions differ from yours on many points, but I’m spitting chips about the way all the original work done by early members of Jim Reeds’ mailing list – most of which is the basis for current ‘ideas’ is being blanked … and now in Koen’s videos, which seem to become more and more sucked into a practice of determining research’s value by less than objective standards.

You may be phlegmatic about it, but I was incensed by Koen’s saying that ‘modern’ research only began with the radiocarbon-14 dating – when you, Neal, Lockerby and others had already reached a consensus as fiirst half of the 15thC., and failure to acknowledge the fact that recognition of multiple scribal hands begin far earlier than Fagin Davis’ revisiting the matter.

So, anyway – the point of this comment to ask which of your posts about the scribal hands, if any, would you prefer me to mention as an example of what I mean when speaking about the cumulative effect of a Voynichero’s pretending no precedent, or earlier research exists for some original insight or opinion they’d prefer the public to believe due to someone else?

If you prefer to maintain a diplomatic silence, I’ won’t refer to a blogpost but cite relevant pages from ‘Curse’.

… and if a certain other high-profile Voynichero should decide to respond instead of Nick.. please don’t. Spend the time seeing if you can’t produce a couple of thousand words’ original research yourself.

Diane: I haven’t seen any of Koen’s videos, but I’ll go and have a peek over the next few days. I tried to build Curse on a carefully curated selection of what I considered good preceding research, and the old mailing list certainly had plenty of smart participants and thoughtful comments, much of which was arguably better than most of what followed.

At the same time, the radiocarbon dating did seem to provide a push into a new era, where a new set of faces came to prominence, along with a new (and, sadly, all too often Baxian) set of research angles. Some of these – like Koen’s – are genuinely interesting and well-researched, but… you know the rest.

Nick,

I’ve always wished the ‘Curse’ came in two parts – the y’know technical-historical part as vol.1 and the Averlino adventure as Vol.2.

No particular ‘scribal hands’ post(s) you’d like linked, then?

Diane: as I recall, I started blogging on “Voynich News” in late 2007, and migrated my posts to ciphermysteries.com in September 2008 or so. It feels a lot more like 30 years ago than 20, and I’m not really sure how such digital archaeology could help you

OK…I feel like I must be misreading/getting the wrong end of the stick here because this point is so well known: “recognition of multiple scribal hands” in the manuscript goes back *at least* as far as Currier in 1976! He confidently asserted there were at least two scribes and speculated that there might be as many as eight. Are you meaning something different here? What am I missing here?

Regardless, Koen is in no way stating that Lisa Fagin Davis is the first to posit this. All he says is “When Lisa Fagin Davis argues that the Voynich manuscript was written by several scribes, I’m inclined to believe her because she is a professional paleographer with years of experience and I’m not.”

The context of this is a small section about how opinions based on professional expertise carry a heavy weight. There is no need to start referencing the history of earlier opinions on this matter in such a video. If Koen had been doing a video on the scribal identifications, things would be different. But he’s not, and you know that.

Nick, I have spent days hunting through volumes published in the 1600s, just to check a footnote So, i’m sure, have you – but if youv’e no more recent comment you’d prefer cited,. I’m happy to cite ‘Curse’.

Diane: Nick, first half 15th Cent.? think again! You sure that assumption fits with Nick’s reckoning pre C14 dating results of 2009. Reminds that we’re still awaiting official confirmation re 1404 – 1438 from the man from Tennessee Greg Hodgins who seems to have gone silent on the subject. Rich SantaColoma might not agree either though Bax might if he was still on speaking terms.

Greg Hodgins’ statement on the analysis during the personal interview.

‘’Although I’m not yet 100 per cent convinced of the accuracy of the dating, it’s probably pretty close.”

I didn’t know that, but Nick was also asked about it.

‘Nick Pelling, the author of ’The Curse of the Voynich‘, told Discovery News.’

What exactly do you mean by ‘official confirmation’.

https://phys.org/news/2011-02-experts-age.html

https://www.nbcnews.com/id/wbna41541365

Alder Buckthorn / Rhamnus Frangula on page 22r is a plant for bees and the three initial words of that page if transformed in a Polish reading script can be read as FIELD OF THE ALDER BEES. All the manuscript shows flowers and it is conceivable that it is a manual for beekeepers.

Peter M…If you’re asking moi, simple answer being that, apart from a press release at the time (I’m thinking 12/2009), there was no follow-up official written document tabled, and that’s a sorry fact nobody seems to have expressed concern over in the years since.

Tavi,

You did not address your remark to anyone, and you posted it here not at my blog, so I’ve hesitated to reply to you.

Thank you for mentioning Currier. I’ll re- read his paper to find that discussion of palaeography. Good of you to bring it to notice.

Your tone suggests a certain confusion between critique of what a scholar produces and criticism of that scholar him/herself.

Put yourself in the position of someone who is studying palaeography – even just Latin paleography. They are among the thousands who have been attracted to Koen’s videos by the tone of the earlier ones, which addressed a few common and pervasive errors in a cool, objective and factual tone.

In the latest video, they get the idea that nobody but Lisa has done anything worthwhile or wort reading about on the question of how many scribes helped make the present manuscript. Those listeners are being misled, and told, more or less that no-one, or no-one worth paying attention to, ever asked or investigated the question.

That’s one reason for my criticism of the video.

The other reason is that – assuming you’re right about Currier’s having looked into this question, Voynich studies has seen three people ask and seriously investigate this question.

Each of them spent days or weeks poring over the manuscript and over texts on the history of Latin palaeography ( no other sort of script was considered) and all three then generously shared their findings, contributing to what we can say about the manuscript. Some scholars, it is true, are more interested in enlarging their public image (take Kircher, for example) but others give their time, labour and even money (technical books aren’t cheap) asking only two things – that their contribution is properly acknowledged – not determinedly ‘blanked’, and that when re-used the content is not misrepresented. Because it’s not about us – it’s about a manuscript.

Feelings of personal trust are neither here nor there. Arguments from authority have variable use-by dates. Again, think of Kircher’s position as an ‘authority’ in his own time, as against now. Imagine where we’d be now if Einstein’s contemporaries ‘blanked’ his contributions to math because he had a boring clerical job in some minor government office.

Evidence and balance of evidence is what matters. Koen’s readers are entitled to know about, so they can form their own opinions about, Currier’s “2-8” scribal hands (as you said), as against Nick’s ‘3’ hands, and Lisa’s ‘5’.

No thumb on the scales.

Bottom right with honeyguide bird atop the skep, depicts a squadron of worker bees in line abreast formation preparing to escort a migrating queen further afield to a new hive or else a new Queen on her first mating venture. That, or dropping her off at home base after getting it off with a few randy drones drones out looking for bit of fresh nooky.

In a comment left on my blog, Stefan points out that this image contains at its centre, a rough sketch resembling a T-O diagram, though we know that by the early fifteenth century Latin mss also use that format to represent the ‘three elements’ of earth, air and water’.

However, supposing it does refer to the three continents recognised for most of the medieval period, then an alternative possibiitity is that the four ‘towers’ represent four notable mountains, one from Europe, one from Africa and 2 from Asia (in which Egypt was included).

I can suggest four, but it’s only a suggestion, not a conclusion.

Upper left – spewing out sparks – Etna or Stromboli. (Europe)

Upper right – the ‘glass’ mountains behind Carthage – signified by the eagle’s inability to find purchase (Africa).

Lower left – Mountains of the Moon, fecund source of the Nile – the half-hidden figure then, perhaps, Sirius/Isis whose emergence marked its rise (Egypt/Asia 1)

Lower right – some notably stable mountain in Asia… maybe Ararat> maybe the ‘paradise’ mountain in Sri Lanka? (Asia 2)

So you’d have 3 mountains unstable, being affected by an element – as e.g. Fire affecting Etna, Water affecting the Mts of the Moon; ‘glass’ (or strong winds?) affecting the Mts in North Africa, but the calm and stable fourth allowing stable occupation. It’s worth mentioning that this is the nearest image to the Voynich map, which is also envisaged in four quarters.

I have to pass on the ‘bees’ idea, or at least a Latin ‘bees’ idea. They just didn’t draw, and certainly didn’t draw bee-hives and bee-keeping like this. Sorry.

How’s about the mountains of Mourne Diane, don’t they rate a mention, you being Irish as Paddy’s pigs and all?..by descent of course not necessarily by association!

Considering the times – first the Mongols’ massive decimations and devastations and then the spread of Plague, it’s not impossible there’s a religious theme here about finding refuge.

I’m thinking of Ps.91 for example. A couple of stanzas

You who dwell in the shelter of the Lord

Who abide in His shadow for life

Say to the Lord

“My refuge, my rock in whom I trust!”…

…You need not fear the terror of the night

Nor the arrow that flies by day

Though thousands fall about you

Near you it shall not come.

In medieval Europe – and doubtless elsewhere – the Psalter was used as a primary-level textbook so its verses would be known by heart.

John,

If we take it that the ‘world’ included in the original Voynich map marks the limit of the original maker’s known world, we must suppose mainland Europe and all beyond the Pillars of Hercules was terra incognita. In fact, the waters of the Atlantic-North Sea, indicated only by huge waves, is referenced only by a mid-fourteenth century addition to the map – its north roundel. So while the nearest comparison I found for the little dragon on f.25 was an object recovered from Clonmacnoise (abandoned by the fourteenth century), and though we know of at least one Irish Franciscan who travelled east to as far as Egypt (Hugo the Illuminator), one can’t overlook the absence of interlace in the Vms. So no Irish theory.. so far.