If the Last Will and Testament written by Andre Bernardin Nageon de l’Estang is genuine (or, at least, perhaps only modestly embellished in the copying) and – as part of that – was indeed written by him, it can only have been written prior to his death in 1750.

I previously also wrote about the intrigue and politicking around La Bourdonnais’ fleet that he hustled together in 1745-1746 in Mauritius, and speculated that Bernardin – himself a lifelong sailor in the Compagnie des Indes – might well have got caught up with that whole operation. But all the same, that was just my guess: the fact that Bernardin died in Port Louis in 1750 provides a solid terminus ante quem regardless.

It further seems likely (to me) that even five years would be an eternity to wait before returning to cached treasure, so the decade 1740-1750 seems a good basic search period to start with. So we might ask: can we find a historical source for Mauritian shipwrecks during the period 1740 to 1750? And if so, can we use that to steer us any closer to a likely source for Bernardin’s treasure?

“Maurice : Une Ile et Son Passé” (1989), by Antoine Chelin

I found a digitised copy of this book online: this runs from 1500 to 1750, and chronologically lists many (though of course not all) events in Mauritius’ history.

The author (who wrote in Mauritian newspapers for many years under the anagrammatic byline “HELNIC”) first published this book in 1973, then released a chunky supplement to it in 1982, before finally merging the two into a single larger book in 1989.

Here, we’re specifically interested in shipwrecks (“naufrages“) and hurricanes (“ouragans“) in the period 1740-1750 on Mauritius. In the following, I’ve used Chelin’s numbering system to make it easy to look up individual events in the original book.

298: 11 Jan 1740: hurricane which caused considerable damage in the bay of Port Louis

325a: 13 Dec 1743: violent hurricane which caused considerable damage to the whole island

337: 17-18 Aug 1744: the shipwreck of the Saint-Géran off the Ile d’Ambre, close to Poudre d’Or, subsequently made famous by Bernardin de Saint-Pierre by his fictionalised version of the event in his novel Paul et Virginie. The ship had a cargo of 54000 Spanish piastres plus machinery for a sugar factory that was being built.

354: 10 Dec 1746: return of Mahé de La Bourdonnais from Madras.

361: 21 Jan 1748: hurricane which caused great damage to boats in the harbour of Port Louis – the Brillant, the Renommée, and the Mars were all beached, and three other boats were lost. “The kilns of Isle aux Tonneliers were destroyed, houses in Port Louis were thrown down; Pamplemousses Hospital

was flattened, the wings of the Monplaisir building in Les Pamplemousses lost their roofs, bridges were washed away, shops in Port Sud-Est were knocked down, the newly-built battery at Trou-aux-Biches was flattened by the waves.“

377: 7 Nov 1748: “departure for India of part of the squadron under the orders of Capitaine de Kersaint. It is composed of the Arc-en-Ciel, Capitaine de Belle Isle, 54 cannons, crew of 400; the Duc de Cumberland, enseigne Mézidern, 20 cannons, crew of 179; and L’Auguste, enseigne de Saint-Médard, 26 cannons, crew of 130.”

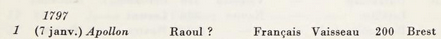

378: 9 Nov 1748: “Departure of the rest of de Kersaint’s squadron, consisting of Alcide, captained by de Kersaint, 64 cannons, crew of 500; Lys, frigate captain Lozier Bouvet, 64 cannons, crew of 476; the Apollon, enseigne de La Porte Barrée, 54 guns, crew of 383; and of the Centaure, ensign de La Butte, 72 guns, crew of 522.”

379a: 26 Nov 1748: arrival of the frigate Cybèle from Pondicherry, announcing the news that the siege of that place by the British had been lifted.

389: 10 Jul 1750: shipwreck of the Sumatra at l’Ile Plate, which had left Port Sud-Est carrying a cargo of wood headed for Pondicherry (14 crew drowned).

A new Bernardin Nageon de l’Estang timeline?

Previously, I had speculated that Andre Bernardin Nageon de l’Estang might have been part of La Bourdonnais’ cobbled-together fleet that sailed to Madras in May 1745. It was certainly true that many Mauritians, rattled by the loss of the Saint-Géran in January 1744, didn’t want to take part: though as a former sailor in the Compagnie des Indes, I suspect Bernardin was unlikely to have been in that group.

In March 1748, (British) Admiral Boscawen arrived at the island with 28 boats en route to Pondicherry, angling for a fight: however, the only French ship he encountered was Capitaine de Kersaint’s Alcide at Port Louis. When Boscawen subsequently arrived off the Coromandel coast in August 1748 in his flagship the Monteran (after a detour to Bourbon in July 1748), his fleet was (according to H. C. M. Austen, p. 21) “the greatest European fleet ever seen in the East“.

Later in 1748, a small French/Mauritian fleet assembled itself under Capitaine de Kersaint. Maybe Bernardin could not say no to joining that small squadron that left Mauritius in November 1848 to try to relieve the siege of Pondicherry. However, they were not to know that the treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle had already been signed on 30th April 1748, making their journey pointless.

And so I can’t help but wonder: might the “treasures saved from the Indus” hidden by Bernardin Nageon de l’Estang have been from a ship wrecked by the huge cyclone that hit Mauritius on 21 January 1748? And might the enlistment Bernardin talks about in his Last Will and Testament have been the (actually unnecessary) squadron under Capitaine de Kersaint that left Mauritius on 7-9 November 1748?

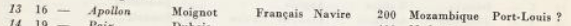

“I’m about to enlist to defend the motherland, and will without much doubt be killed, so am making my will. I give my nephew the reserve officer Jean Marius Nageon de l’Estang the following: a half-lot in La Chaux River district of Grand-Port, île de France, plus my treasures saved from the Indus.”

Note: full letter here

It’s an interesting possible timeline, that (if true) would answer some of the questions I’ve had about timing that have long seemed very slightly off. Even so, the account does remain fairly hypothetical: though on the positive side, it does perhaps suggest some ideas about where to look next.

So… where next for this?

The first thing I’d like to see are contemporary accounts of the hurricane that hit Mauritius on 21 January 1748. The information Chelin reports must (surely) have come from somewhere, but from where? Mauritian newspapers only go back (very incompletely) to 1777 – Le Cernéen and Le Mauricien only started in 1832 and 1833 respectively.

I should perhaps add that the Wikipedia page on tropical storms in the Mascarenes only mentions two from the period 1740-1750 (though note that Grant’s book includes a long section on hurricanes on Bourbon compiled by the Abbé de Caille?):

- March 8, 1743 – A strong cyclone passed near Mauritius.

- February 1748 – A strong storm

Note that a letter discussing the 1743 cyclone is quoted in Garnier and Desarthe (2013):

Letter of the governor of the Ile-de-France (Mauritius) of March 8th, 1743:

We had a hurricane on March 8th. The big rashness of the wind lasted only from ten o’clock in the evening till two o’clock at night. Several vessels ran aground in the port because of very high waves which reached the store of the port. The harvest was almost completely destroyed, in particular the corn, the potatoes and the sugar canes. On the other hand, the rice and the manioc were protected. As soon as our port (Port Louis) will be repaired, I shall send to you by boat of the peas of the Cape (South Africa) and the beans which you can distribute in the poorest and to the blacks.

As far as the Jan/Feb 1748 Mauritian hurricane goes, I did find a (fairly miserable) letter from Baron Charles Grant de Vaux dated 10 March 1748 (pp. 293-294):

We have been informed that fifteen ships have been dispatched from the East, laden with provisions for our islands ; but unfortunately the English fell in with them, and, being superior in point of force, have taken them all, except a small vessel, which escaped to make us acquainted with our misfortunes. We live at present in a most wretched state of incertitude, in want of every thing ; and, to complete our misery, afflicted with a continued drought, which has known no interval throughout the year, but from an hurricane that visited us during the last month. It ravaged every thing, and occasioned many fatal accidents. Several persons were killed and wounded during its continuance ; and, to complete our distresses, it was succeeded by a cloud of locusts, which devoured whatever the hurricane had not laid waste. Such is our present situation, &c. &c.

For other sources, I haven’t yet found any journaux de bord covering 1748 (the Achilles’ only goes up to 1747), nor any prize papers, and the Log of Logs starts from 1788, alas. I’ve also asked Professeur Garnier if his researchers found any sources on the 1748 hurricane. Myself, I haven’t yet found anything relevant in gallica.fr, though the chances that something useful is there are surely quite high. The French maritime archives are similarly daunting and huge.

But at least I’m looking for something now. 🙂