Darrell Huff’s (1954) “How to Lie With Statistics” is a twentieth century classic that’s well worth reading (I have a well-thumbed copy on my bookshelf that I bought back in the 1980s). It’s basically a breezy introduction to statistics, that concentrates largely on how people get things wrong in order to get across the general idea of how you might (possibly, hopefully) try to get things right in your own work.

A journalist rather than an academic statistician, Huff’s book ended up selling more than 1.5 million copies. You can hear echoes of his reversed-expectations presentation in numerous other book titles, such as Bill Hartston’s “How to Cheat at Chess”.

Sadly, The Truth Is Much, Much Worse

When later I did statistics modules at University, the awful truth slowly dawned on me: even though tools (such as Excel) make it easy to perform statistical procedures, stats really isn’t just a matter of “running the numbers”, cranking out an answer, and drawing some persuasive-looking graphs.

Even just conceiving a statistical experiment (e.g. something that’s based on good data, and that stands a chance of yielding meaningful results) is extraordinarily hard. Designing statistical experiments (e.g. understanding the sampling biases that are inevitably embedded in the data, and then working out how to work around them) is also hugely tricky. Executing them is no mean feat either: and then – finally – interpreting them is fraught with difficulty.

In general, my own experience of statistical experiments is that at least half are fatally misconceived; of the remainder, half are horribly misdesigned; of the remainder of that, at least half are sadly misexecuted; and of the remainder of that, at last half of the results are tragically misinterpreted. Note that the overall success rate (<5%) is for people who broadly know what they’re doing, never mind idiots playing with Excel.

A Story About Stats

Back when I was doing my MBA, one of the final marked pieces was for the statistics module. When I took a look at the data, it quickly became clear that while most of the columns were real, one in particular had been faked up. And so I wrote up my answer saying – in a meta kind of way – that because that (fake) column was basically synthetic, you couldn’t draw reliable conclusions from it. And so the best you could do in practice was to draw conclusions from the other non-synthetic columns.

I failed the module.

So, I made an appointment with the lecturer who marked it, who also happened to be the Dean of the Business School.

- I said: Why did you fail this piece?

- He said: Because you didn’t get the right answer.

- I said: But the column for the ‘right’ answer is fake.

- He said: I don’t think so.

- I said: Well, look at this [and showed him exactly how it had been faked]

- He said: Oh… OK. I didn’t know that. But… it doesn’t matter.

- I said: errrm… sorry?

- He said: you’ve got a Distinction anyway, so there’s no point me changing this mark

And so I still failed the statistics module.

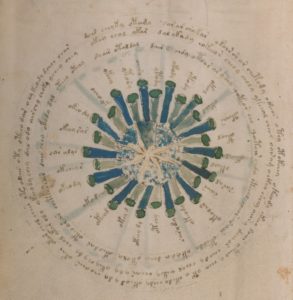

The Voynich Manuscript and Stats

If you think Voynich Manuscript researchers who run statistical tests on Voynichese are somehow immune to these fundamental hazards, I don’t really think you’re paying enough attention.

Until you accept that the core problems inherent in Voynichese transcriptions – there are many, and they run deep – will inevitably permeate all your analyses, you really are just running the numbers for fun.

The main things that bother me (though doubtless there are others that I can’t think of right now):

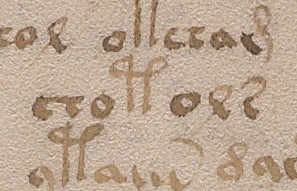

- Transcription assumptions

- Transcription error rates

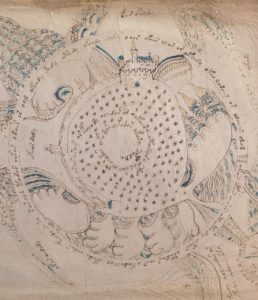

- Running tests on the whole Voynich Manuscript, rather than on sections (e.g. Q13, Q20, Herbal-A)

- How Voynichese should be parsed into tokens (this has bugged me for 20 years!)

- Copying errors and Voynichese “weirdoes”

- The bifolios being out of order

- Whether there is a uniform ‘system’ underlying both Currier A and Currier B

- The problems with top-line text

- The problems with line-initial letters

- The problems with line-final letters

- etc

With so many parallel things to consider, I honestly think it should be no surprise that most attempts at Voynich analysis fail to achieve anything of value.

Voynich Theories

I have no doubt that researchers do their best to be rational and sensible, but many Voynich theories – or, perhaps more accurately, Voynich ‘approaches’ – are built upon a fundamentally flawed statistical ‘take’, e.g. that Voynichese is just a simple (but highly obscure) text.

Unpopularly, this seems to be true of just about all ‘Baxian’ Voynich linguistic analyses. Statistically, nothing supports the basic assumption of a ‘flat’ (but obscure) language. In fact, Voynichese is full of confounding, arbitrary, difficult, unlanguagelike behaviours (see the incomplete list above), all of which you have to compensate for to get your data to a point where you even begin to have something remotely language-like to work with. But hardly anybody ever does that, because it’s too tricky, and they’re not genuinely invested enough to do the ‘hard yards’.

It’s also true of Gordon Rugg’s table ‘take’; and of just about all simple ciphers; and – also unpopularly – of hoax theories (why should meaningless text be so confounded?) And so forth.

The sad reality is that most researchers seem to approach Voynichese with a pre-existing emotional answer in mind, which they then true to justify using imperfect statistical experiments. More broadly, this is how a lot of flawed statistical studies also work, particularly in economics.

In fact, statistics has become a tool that a lot of people use to try to support the lies they tell themselves, as well as the lies their paymasters want to be told. This is every bit as true of Big Oil and alt.right politics as of Voynichology. Perhaps it’s time for an even more ironic 21st century update to Darrell Huff’s book – “How To Lie To Yourself With Statistics”?