(This is René Zandbergen’s translation of Jens Sensfelder’s (2003) short article on the crossbowman in the Voynich Manuscript.)

* * * * * * * *

The crossbow archer in the Voynich Manuscript: a tentative dating

(Author: Jens Sensfelder, 21st December 2003)

(Converted to HTML by Nick Pelling, 30th December 2003)

(Translated by René Zandbergen, 2 January 2004)

(Translation checked by Elmar Vogt and Nick Pelling)

(Note: diagrams to follow!)

The following presents a tentative dating of the above-mentioned illustration, which shows a man holding a cocked crossbow in his hands. The analysis is (for the most part) restricted to the crossbow itself.

Subject:

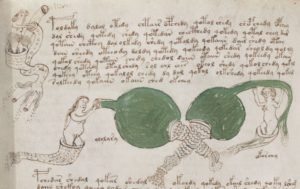

An illustration of an archer holding a crossbow, in the so-called “Voynich Manuscript” (Beinecke MS 408), fol 73v (Annex 1).

A walking archer is holding in his hands a cocked crossbow, charged with a bolt and ready to be shot, at about waist height. An analysis of the garments of the man would certainly add valuable information for dating the illustration. For this I refer to the relevant experts in that field.

Description:

-

The illustration of the crossbow is a line drawing. Only the bow and the stock have been filled in with colour (though only a monochrome reproduction was available for study).

-

The stock is a straight shaft, tapering down towards the archer. It is not possible to determine whether its cross-section is rectangular, round or oval.

-

The archer’s right arm partly covers the end of the stock and it is therefore not possible to determine its total length exactly. The important [distance from bow to latch : distance from latch to end] ratio can be determined fairly accurately as 1 : 1.3 (though if longer, the ratio might be larger).

-

The release mechanism is a long straight trigger bar with a (90°) right angle.

-

The bow has been drawn in two lines and shows the typical recurve shape. It becomes narrower towards the extremes. At the ends its thickness is only that of the nib used to draw the figure.

-

The bowstring has not been attached to the ends of the bow, but to a point in the concave part of the bow. The bowstring has no visible loops or knots.

-

The stirrup of the crossbow has an oval shape.

- The bolt is drawn as a thick line and has a triangular tip as well as an increased diameter towards the rear.

Analysis:

On the basis of the stock length and the trigger bar, one can exclude an Asian (4.; p. 15), African (4.; p. 214ff) or Indian (4.; p. 216) origin of the crossbow. The crossbow will therefore only be compared against the European tradition.

a) Archer

The archer is most probably a hunter, because he is neither carrying any other weapons nor wearing any protective armour.

His head gear appears to me to be a long rolled-up cowl (which was quite popular in the 14th Century (3.; p. 20)), because of its turban shape and the rolled-up part hanging down behind it.

The archer is not holding the crossbow properly: one hand has been drawn on the trigger bar and the other above the stock. The inept way in which the hands have been drawn lets us conclude that the artist had problems with this detail. He has just drawn the hands in such a way as to show that the archer is holding the weapon in his hands.

b) Bow

The bow in the illustration is most probably a composite bow. There are several reasons for this:

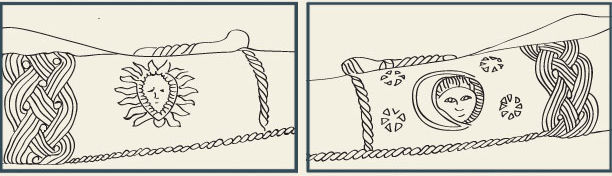

The use of horn in bows was copied from the Saracens during the crusades, and from then on widely used (especially in Central Europe) for crossbows. The shape of the Turkish bow was introduced at about the same time, which would explain the recurve bow shape of the early crossbows (cf. 5.). Only after the mid-14th Century were horn bows made more solid and compact, and changed into the ‘simple’ circle-arc shape. Quite probably there would have been a transition phase during which both types of bows would have coexisted (Annex 2, cf. Figures 21 and 24: Lutrell Psalter 1340).

c) Stock, release mechanism

The latching mechanism is hidden by the bolt, which is not represented correctly. From the presence of a trigger bar, one may conclude that the latch is a ‘nut latch’. The latch is located relatively far back (i.e. towards the rear of the stock). One may assume that this is the case only for very early types of crossbows. The Roman crossbow, for example, placed the latch at the very end of the stock. The gothic crossbow placed it at two fifths from the front of the stock, and in the Renaissance it was at one third from the front. The right angle in the trigger bar is quite characteristic and belongs strictly to the 14th Century. Following Harmuth (4.; p. 109), this form developed from the obtuse angle that can be observed in many illustrations (cf. 6, also annex 6). Later trigger bars are not straight but always slightly curved. The crossbow in the illustration lacks a bridle, and no alternative attachment of the bow to the stock is evident.

Comparable illustrations/originals:

I am not aware of any crossbow illustrations in connection with the zodiac figure Sagittarius. I also don’t know any illustrations of crossbowmen in calendars. Below, some comparable crossbows and illustrations of crossbows will be compared to the one being studied. Already in 1235 Villard de Honnecourt showed a crossbow trap in his treatise on the ‘Bauhuettenwesen’ [masonic guilds during the construction of cathedrals] (see also Annex 3). This illustration is similar to ours in many respects, even though Honnecourt has drawn it far more accurately. Eschenbach’s epic poem Willehalm (1320) shows crossbows very similar to ours (see also Annex 4). The soldiers are using horn bows with a recurve shape and straight stocks. Similarly, the attachment of bows to the stocks are not drawn. Furthermore, the important [distance from bow to latch : distance from latch to end]ratio is similar to our crossbow. An original Gothic era crossbow is kept in the Stadtmuseum of Cologne (Inv.Nr. W 1109, 5., see also Annex 2). This crossbow, which Harmuth dates to the 14th Century, also has a right-angled trigger bar. (It is worth noting that in the attached illustration the stirrup is missing, and the bow should be attached to the stock rotated by 180°. Cocking the bow would cause it to take on the familiar recurve shape.) However, this piece does already have a curved stock, typical for a Central European weapon, which ours evidently does not. A crossbow of this type is show in Wenzel’s bible of around 1390 (see also Annex 5), where, unfortunately, the trigger bar is not visible.

Dating:

Based on the above analysis I would date the crossbow as drawn in the illustration to the first half of the 14th Century. A more precise dating is not possible in my opinion, since at any time, also regionally, several types of crossbows would be used (and drawn).

As already indicated in the beginning, the crossbow belongs to the European tradition, but a more precise geographical identification is unfortunately not possible for reasons which will be explained below.

Undoubtedly, the illustrator has drawn the shape of the bow very accurately. Its back-and-forth curves are recognised easily also by the layman and drawing it doesn’t require any great dexterity whatsoever. Looking at the bow (and taking into account the analysis presented above), the influence of the Saracen bow is easily recognisable.

The straight stock is typical for the early 14th Century. Taking into account that the illustrator has observed the shape of the bow and represented it accurately, he would have surely done the same with the stock.

The differentiation between the Central and Western European crossbow types occurred in the course of the 14th Century. At that time, both types already show the characteristic shape of the stock. Hence, the straight stock clearly belongs to the era before this development and one cannot therefore decide whether the crossbow belongs to the Central or Western European tradition.

The right-angled trigger bar is already common at this time; earlier crossbows’ trigger bars all have an obtuse angle. The right angle appears to have been noticed specifically by the illustrator, as he depicts it quite accurately. The (previously-mentioned) fact that the trigger bars of later crossbows are all curved, as in the Hunting books of Gaston Phebus, speaks against a later origin of this crossbow.

References:

| 1. |

Boeheim, Wendelin |

Handbuch der Waffenkunde, Leipzig 1890 |

| 2. |

Credland, Arthur G |

The Crossbow in Britain, in: The Royal Armouries

Yearbook, 6/2001 |

| 3. |

Embleton, Gerry |

Ritter und Söldner im Mittelalter, Herne 2002 |

| 4. |

Harmuth, Egon |

Die Armbrust, Graz 1986 |

| 5. |

Harmuth, Egon |

Eine Einfußarmbrust der Hochgotik, ZfHWKK 1978 |

| 6. |

Harmuth, Egon |

Die Armbrustdarstellungen des Haimo von Auxerre, ZfHWKK

1970 |

Source of Annexes:

All Annexes from 4.

Glossary:

| Bridle |

The ropes/cords binding the stock and the bow together |

| Cock |

To pull the bowstring back into the latched position, so that it can be released (thus shooting away the bolt or arrow) |

| Composite bow |

Bow made of several materials (typically one would use horn, wood and string). This also explains the term “horn bow” |

| Latch |

Mechanism for holding the bowstring in cocked position and for releasing the bowstring when the trigger bar is squeezed |

| Nut latch |

Cylindrical latch, usually made of ivory or antler |

| Recurve |

Shape of the bow which has a double curvature (when cocked) |

| Stirrup |

Ring at the front of the crossbow, into which the archer would insert his foot while cocking the bow |

| Stock |

The shaft of the crossbow |

Afro-Portuguese Horn #101 (from

Afro-Portuguese Horn #101 (from