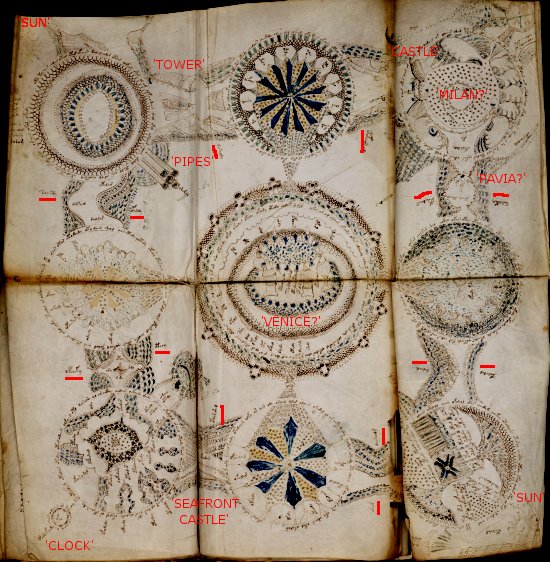

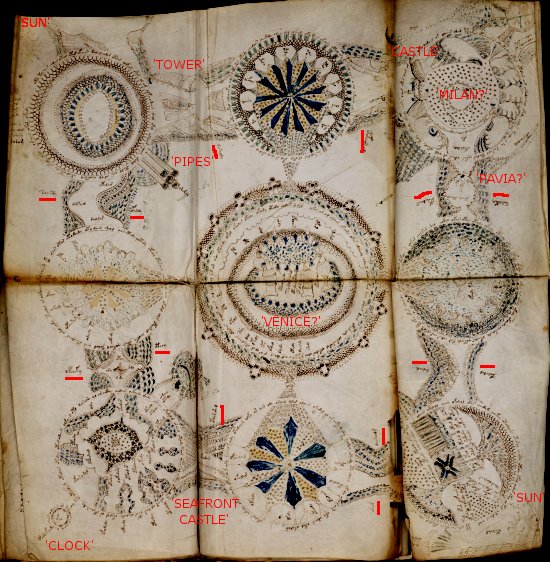

For the most part, constructing plausible explanations for the drawings in the Voynich Manuscript is a fairly straightforward exercise. Even its apparently-weird botany could well be subtly rational (for example, if plants on opposite pages swapped their roots over in the original binding, in a kind of visual anagram), as could the astronomy, the astrology, and the water / balneology quires (if all perhaps somewhat obfuscated). Yet this house of oh-so-sensible cards gets blown away by the hurricane of oddness that is the Voynich Manuscript’s nine-rosette page.

If you’re not intrigued by this, you really do have a heart of granite, because of all the VMs’ pages, this is arguably the most outright alien & Codex Seraphinianus-like. Given the strange rotating designs (machines?), truncated pipes, islands, and odd causeways, it’s hard to see (at first, second and third glances) how this could be anything but irrational. Yet even so, those who (like me) are convinced that the VMs is a ‘hyperrational’ artefact are forced to wonder what method there could be to this jumbled visual madness. So: what’s the deal with this page? How should we even begin to try to ‘read’ it?

People have pondered these questions for years: for example, Robert Brumbaugh thought that the shape in the bottom left was a “clock” with “a short hour and long minute hand”. However, now that we have proper reproductions to work with, his claim seems somewhat spurious, for the simple reason that the two “hands” are almost exactly the same length. Mary D’Imperio (1977) also thought the resemblance “superficial”, noting instead that “an exactly similar triangular symbol with three balls strung on it occurs frequently amongst the star spells of Picatrix, and was used by alchemists to mean arsenic, orpiment, or potash (Gessman 1922, Tables IV, XXXIII, XXXXV)” (3.3.6, p.21).

Back in 2008, Joel Stevens suggested that the rosettes might represent a map, with the top-left and bottom-right rosettes (which have ‘sun’ images attached to them) representing East and West respectively, and with Brumbaugh’s “clock” at the bottom-left cunningly representing a compass in the form of the point of an arrow pointing towards Magnetic North. You know, I actually rather like Joel’s idea, because it at least explains why the two “hands” are the same length: and given that I suspect that there’s a hidden arrow on the “bee” page and that many of the water nymphs may be embellished diagrammatic arrows, one more hidden arrow would fit in pretty well with the author’s apparent construction style.

This same idea (but without Joel’s ‘hidden compass’ nuance) was proposed by John Grove on the VMs mailing list back in 2002. He also noted that many of “the words appear to be written as though the reader is walking clockwise around the map. The words inside the roadway (when there are some) also appear to be written this way (except the northeast rosette by the castle).” I’ve underlined many of the ’causeway labels’ in red above, because I think that John’s “clockwise-ness” is a non-obvious piece of evidence which any theory about this page would probably need to explain. And yes, there are indeed plenty of theories about this page!

In 2006, I proposed that the top-right castle (with its Ghibelline swallowtail merlons, ravellins, accentuated front gate, spirally text, circular canals, etc) was Milan; that the three towers just below it represented Pavia (specifically, the Carthusian Monastery there); and that the central rosette represented Venice (specifically, an obfuscated version of St Mark’s Basilica as seen from the top of the Campanile). Of course, even though this is (I think) remarkably specific, it still falls well short of a “smoking gun” scientific proof: so, it’s just an art history suggestion, to be safely ignored as you wish.

In 2009, Patrick Lockerby proposed that the central rosette might well be depicting Baghdad (which, along with Milan and Jerusalem, was one of the few medieval cities consistently depicted as being circular). Alternatively, one of his commenters also suggested that it might be Masijd Al-Haram in Mecca (but that’s another story).

Also in 2009, P. Han proposed a link between this page and Tycho Brahe’s “work and observatories”, with the interesting suggestion that the castle in the top-right rosette represents Kronborg Slot (which you may not know was the one appropriated by Shakespeare for Hamlet), with the centre of that rosette’s text spiral representing the island of Hven where Brahe famously had his ‘Uraniborg’ observatory. Kronborg Slot was extensively remodelled in 1585, burnt down in 1629 and then rebuilt: but I wonder whether it had swallowtail merlons when it was built in the 1420s? Han also suggests that other features on the page represent Hven in different ways (for example, the three towers marked ‘PAVIA?’ above); that the pipes and tall structures in the bottom-right rosette represent Tycho’s ‘sighting tubes’ (a kind of non-optical precursor to telescopes); that one or more of the mill-like spoked structures represent(s) Hven’s papermill’s waterwheel; and that the central rosette represents the buildings of Uraniborg (for which we have good visual reference material). Han’s central hypothesis (on which more another day!) is that the VMs visually encodes information about various supernovae: the suggestion here is that the ‘hands’ of Brumbaugh’s clock are in fact part of the ‘W-shape’ of Cassiopeia, which sits close in the sky to SN 1572. Admittedly, Han’s portolan-like ‘Markers’ section at the end of the page goes way past my idea of being accessible, but there’s no shortage of interesting ideas here.

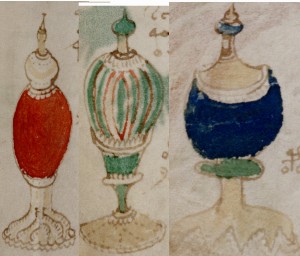

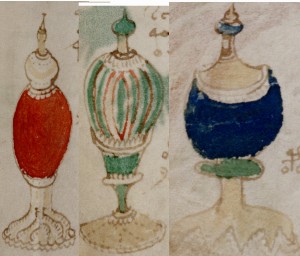

Intriguingly, Han also points out the strong visual similarity between the central rosette’s ‘towers’ and the pharma section’s ‘jars’: D’Imperio also thought these resembled “six pharmaceutical ‘jars'”. I’d agree that the resemblance seems far too strong to be merely a coincidence, but what can it possibly mean?

Finally, (and also in 2009) Rich SantaColoma put together a speculative 3d tour of the nine-rosette page (including a 3d flythrough in YouTube), based on his opinion the VMs’ originator “was clearly representing 3D terrain and structures”. All very visually arresting: however, the main problem is that the nine-rosette page seems to incorporate information on a number of quite different levels (symbolic, structural, physical, abstract, notional, planned, referential, diagrammatic, etc), and reducing them all to 3d runs the risk of overlooking what may be a single straightforward clue that will help unlock the page’s mysteries.

All in all, I suspect that the nine-rosette page will continue to stimulate theories and debate for some time yet! Enjoy! 🙂