Though (as was apparent from the rapid social media take-up of yesterday’s XKCD webcomic) the Voynich Manuscript is now firmly wedged in the cultural mind, sadly the level of debate on it is still stuck circa 1977 – and if anything, Gordon Rugg’s foolish “hoax” claims have helped to keep it there.

But it is demonstrably written in cipher: and so this post tells you why I’m certain it’s a cipher, how that cipher works, and what you can do to try to break it. I’m happy to debate this with people who disagree: but you’ll have to bear in mind that as far as this goes, I’m just plain right and you’re just plain wrong. 🙂

1. What does the Voynich Manuscript resemble?

Firstly, the overwhelming majority of the Voynich Manuscript is written using only 22 or so letter-shapes: generally speaking, this is the size of a basic European alphabet. Voynichese therefore visually resembles an ordinary European language.

Secondly, even though most of its letter shapes are unknown or unusual, four of them (“a”, “o”, “i”, and “e”, though this last one is styled as “c”) closely resemble vowels in European languages – not only in shape, but also because if you read these as vowels (precisely as the main EVA transcription does), you end up with many CVCVCV (consonant-vowel) patterned words that seem vaguely pronounceable.

Thirdly, dotted through the Voynich Manuscript is a family of letter-groups that look like “aiv”, “aiiiv”, “aiir”, etc. To most contemporary eyes, this looks like some kind of curious language-pattern: but to European people in the 13th to 16th centuries, this denoted one thing only: page references.

- The “a” denotes the first quire (bound set of folded vellum or paper leaves), “quire a”.

- The “i” / “ii” / “iii” / “iiii” denotes the folio (leaf) number within the quire (in Roman numbers).

- The “r” / “v” denotes “recto” / “verso”, the front-side or rear-side of the leaf.

Circa 1250-1550, this “mini-language” of page references was universally known and recognized across Europe: and hence “aiiv” denotes “quire a, folio ii, verso side” and nothing else.

Therefore, the Voynich Manuscript resembles a document written in a 22-letter European language, contains obvious-looking vowel-shapes that are shared with existing European languages, and scattered throughout apparently has copious page-references to pages within its first quire.

However, what even very clever people continue to fail to notice is that these three precise things (the compact alphabet, the obvious-looking vowels, and the page references) have an exact corollary: that this does not resemble ciphertext – for even by 1440, most European cipher-makers knew enough about the vulnerabilities of vowels to disguise them by use of homophones (i.e. using multiple cipher symbols for the vowels). A ciphertext would not contain unenciphered vowels, not unenciphered page references.

The correct answer to the question is therefore not only that the Voynich Manuscript does resemble an unknown (but CVCVCV-based) European language studded with conventional Roman number page references, but also that it simultaneously does not resemble a ciphertext.

2. Why is the Voynich Manuscript not what it resembles?

I think the big clue is the fact that the page references don’t make any sense as page references.

For a start, even though the Voynich Manuscript probably consisted of fifteen or more quires, the page references that appear throughout its text only ever appear to refer to quire “a” (the first quire). What’s more, the first quire appears not to be marked with any form of “a” marking, which is curious because the whole point of quire signatures was to make sure that the binder bound them together in the correct order. Another odd thing is that there only appears to be references to the first six pages of the first quire.

All very strange: but the biggest giveaway comes from the statistics. Counting the number of instances of the different page references, you’ll see that page references to verso pages apparently outnumber page references to recto pages by eight times. Here are the raw counts (from the Takahashi transcription):-

air ( 564) aiir ( 112) aiiir ( 1)

aiv (1675) aiiv (3742) aiiiv (106)

So, even though these superficially resemble page references, there is absolutely no evidence to suggest that this is what they actually are. In fact, the statistics imply the opposite – that despite their visual resemblance to page references, these are not actually page references.

And if it is correct that these are actually something else masquerading as page references, the entire visual-resemblance house of cards collapses – that is, if things are not what they seem, the other visual presumption (that this is a simple CVCVCV-based European language) necessarily falls down with it.

3. If the page references aren’t page references, what are they?

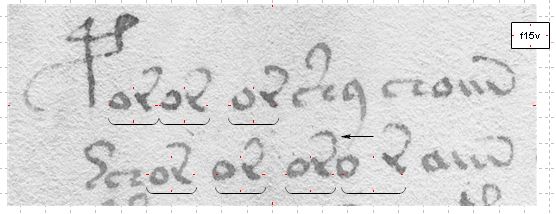

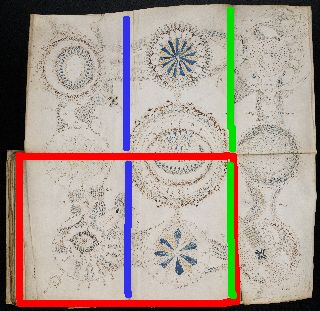

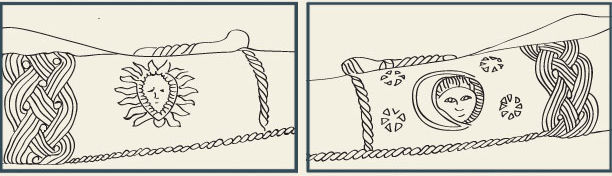

This is precisely the right question to ask: and so, when I visited the Beinecke Library in early 2006, I decided to spend some time looking at a single page containing plenty of clearly-written page references (as described in The Curse of the Voynich, pp.164-168) to try to answer it.

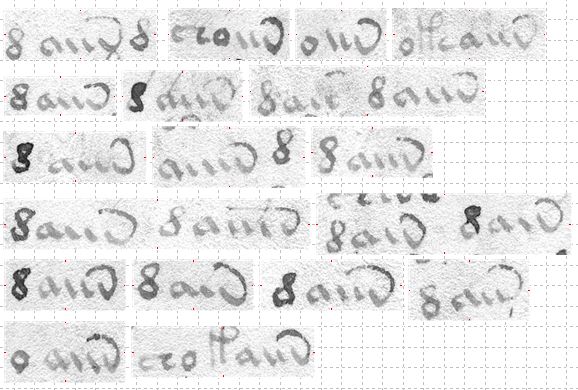

I chose page f38v, from which here are all the page reference letter clusters – can you now see what it took me hours and hours to notice?

The first thing I (eventually) noticed was that there was something a little odd about the top part of the “v” letter (which EVA wrongly transcribes as “n”, incidentally). Specifically, that many of the clusters appear to have been written using two inks – one forthe main “aiiv” part, and another (often slightly darker) one for the scribal “flourish” at the top.

But then… once you start looking specifically at the “v flourishes”, the next thing you might notice is that some appear to have a dot at the (top-left) end of the v-flourish.

The final thing you might notice is that these dots tend to appear in different places relative to the “aiiv” frame.

My conclusion is that what is happening here is steganography – that the position of the dot at the end of the v-flourish is what (possibly together with the choice of cluster) is enciphering the information here.

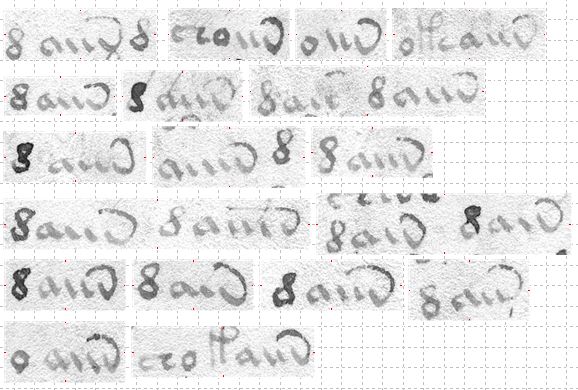

But what information is being enciphered in this way? I strgonly suspect that it is enciphering Arabic numbers 1-5 (probably with longer flourishes denoting larger numbers), and with “oiiv” clusters perhaps denoting 6-10. This might explain why we see so many of these “page references” immediately following each other (the famous “daiin daiin” pattern): each “page reference” therefore represents a digit within a multi-digit Arabic number.

However, what is strange is that this is only basically true for “Currier A-language” pages (Prescott Currier noted that, to a large degree, the text in Voynich Manuscript pages behaves in one of only two different ways): for Currier B pages, what seems to happen is that the information is enciphered by using different shaped flourishes for the final “v” character, and no dot.

From all this, I think I can reconstruct how the Voynich Manuscript’s cipher system evolved during its writing. In the early (Currier A) phase, some kind of data (probably Arabic numbers) were steganographically hidden by writing page-reference-like “aiiv” groups and placing a single dot above them. At a later date, however, the author decided (rightly, I think) that this was too obvious, and so went through the text hiding the dots by converting them into flourishes. Whereas in the later (Currier B) phase, the author decided to evolve the writing system to encipher the same data in a subtly different way (though still relying on the basic “page-reference” shape as a starting point).

And so the correct answer to the section’s question is: even though the “page reference” groups resemble page references, I think that they are cryptographic nulls designed to give the author sufficient visual space on the page to steganographically hide something completely different – probably Arabic numbers.

Of course, existing EVA transcriptions capture only the covertext (the nulls), while the actual data is enciphered in the dots hidden by the flourishes. But you have start somewhere, right? 🙂

4, What, then, is Voynichese’s CVCVCV structure concealing?

I am certain that the Voynich Manuscript’s apparent “consonant-vowel”-like structure is another visual trap into which the existing EVA transcription (unfortunately) helps to push people. By making Voynichese seem vaguely pronounceable (“otolal”, “qochey”, “qokeedy”, etc), EVA discourages us from looking at what is actually going on with the letters, while also falsely bolstering the confidence of those sufficiently deceived into believing (wrongly) that Voynichese is written in a real language. Basically, anyone who tells you it’s written in an archaic language has fallen into a gigantic intellectual trap first set five centuries ago.

But what of the CVCVCV structure? Where does that come from?

For the most part, I think that it arises from a late cipher stage known as “verbose cipher” (i.e. enciphering a single plaintext letter as two ciphertext letters). Though not all letters behave in this way, it certainly goes a very long way to explain the behaviour of common groups such as: qo, ol, al, or, ar, ot, ok, of, op, yt, yk, yp, yf, cth, ckh, cfh, cph, ch, sh, air, aiir, od, eo, ee, and eee. If you decompose the text into these subgroups (i.e. that these groups encipher individual tokens in the plaintext) while remembering to parse the “qo” group first, all the superficial CVCVCV behaviour disappears – and (I contend) you will find yourself very much closer to a kind of raw ciphertext stream that is more easily broken.

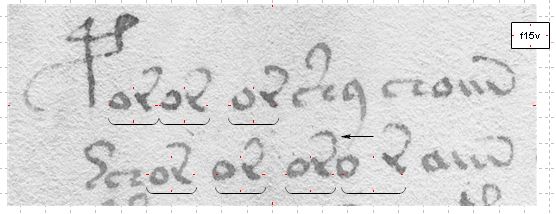

As supporting evidence, I point to those few places where the author has “twiddled” with the final code-stream to try to disguise obvious repeated patterns, arising from repeated letters in the plaintext (code-makers hate repeated patterns in their ciphertext). Perhaps the most notable of these is on f15v, where the “or” pattern appears three times in succession on line 1, and four times in a row on lines 2:-

I think that the author has added spaces in here to try to disguise the repeated “or” group: in line 1, he has inserted a space to turn “ororor” into “oror or“, while in line 2 he has inserted three spaces to turn “orororor” into “or or oro r“. I’m not fooled by this – are you?

I predict here that that “or” is enciphering “c” or “x” (probably “c”), and that the plaintext reads “ccc … cccc”: but you guessed that already, right?

5. Even if this is right, how does it help us break the Voynich?

I don’t believe for a moment that this explains the whole of the Voynichese cipher system: there are plenty of subtly surprising features that any proposed solution would also need to explain, such as:-

- Precisely how (and why) Currier A and Currier B differ (for example, the whole word-initial “l” thing)

- Why “yk / yt / yf / yp” occur more in labels than in normal paragraphs

- Why so few non-trivial words appear more than once across the whole manuscript text

- What “4o” codes for (I suspect a common initial-letter expansion, i.e. [qo] + ‘c’ –> ‘con’)

- What word-initial “8” codes for (I suspect “&”)

- What non-word-initial “8” and “9” code for (I suspect ‘contraction’ and ‘truncation’)

- Whether the ciphering system is stateless or stateful (but that’s another story)

- What “Neal keys” denote (but that’s another story, too)

- etc

However, what I do believe is that all the above lays down the basic groundwork from which any sensible cipher attack would need to launch forwards. I do not share the widely-held pessimistic view that the Voynich is somehow intrinsically unbreakable – on the contrary, it is an all-too-human artefact from a specific time (between 1450 and 1500) and place (probably Northern Italy, though Germany is possible too), and the craft techniques it deftly uses to conceal its content from us are both far from invisible and far from infallible.

If you take the basic steps I describe above to look beyond the deliberate deception and the mythology, then I am certain you will find yourself on the right path towards seeing clearly both what the Voynich Manuscript actually is and how its cipher system works. Let me know when you’ve broken it! 🙂

Incidentally, there’s plenty more related stuff in my 2006 book (which is where the two diagrams above came from, p.165 and p.160 respectively)… but you knew that already, I’m sure. 🙂

Afro-Portuguese Horn #101 (from

Afro-Portuguese Horn #101 (from