To my eyes, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle left two quite distinct legacies. The first, of course, was Sherlock Holmes, his searingly-flawed-but-unstoppably-insightful detective, whose long shadow still hangs over the entire detective fiction genre, 130+ years after A Study in Scarlet.

Yet the second was Conan Doyle’s literary conceit that one can combine wide-ranging observation with pure deduction (as opposed to merely providing a convincing scenario) so powerfully that it can completely reconstruct precisely what happened in cases of murder – which (with all legal caveats for accuracy) would need to be “beyond reasonable doubt”.

The first is fair enough, but the second… has a few issues, let’s say.

“Whatever Remains…”

“How often have I said to you that when you have eliminated the impossible, whatever remains, however improbable, must be the truth?” said Holmes in The Sign of Four, H&W’s second novel-sized outing. (Conan Doyle reprised the quote in the short stories The Adventure of the Beryl Coronet and The Adventure of the Blanched Soldier). Arguably one of the most famous Sherlock Holmes lines, this appeals not only to Holmes’ ultimate power of deduction, but also to his implicit omniscience.

Inevitably, this is precisely what the Rational Wiki’s Holmesian Fallacy web page skewers so gleefully, which itself is no more than a nice summary of numerous articles all arguing the same basic thing: that because Holmes could not possibly have conceived all the possible explanations that fitted a given case’s facts and observations, he could not have eliminated all the impossible ones.

Deduction by elimination is OK for maths problems (which are constrained by the walls of their strong logical structure), but it’s far from satisfactory for murder. My best understanding is that proof of murder is now far more often to do with demonstrating a direct forensic connection, i.e. proving a direct evidential connection between a victim’s death and the accused. Once this link is made, proving the precise details is arguably less important: that such a link has been made at all is normally enough to tell the lion’s share of a story beyond reasonable doubt.

All of which would be no more than a legalistic literary footnote for me, were it not the case that in (I would estimate) the majority of unsolved cipher theories, this kind of specious argument is wheeled out in support of the theorist’s headline claim.

Can we ever eliminate all the other possibilities in our search for the historical truth, thus rendering our preferred account the last Holmesian man standing? The answer is, of course, no: but in many ways, even attempting to do this is a misunderstanding of what historical research is all about.

Instead, once we have eliminated those (very few) hypotheses that we can prove to be genuinely impossible with the resources available to us, we then have to shift our focus onto constructing the best positive account we can. And we must accept that this will almost never be without competitors.

“The Curious Incident”

Gregory (Scotland Yard detective): “Is there any other point to which you would wish to draw my attention?”

Holmes: “To the curious incident of the dog in the night-time.”

Gregory: “The dog did nothing in the night-time.”

Holmes: “That was the curious incident.”

According to Holmes, “I had grasped the significance of the silence of the dog, for one true inference invariably suggests others….Obviously the midnight visitor was someone whom the dog knew well. It was Straker who removed Silver Blaze from his stall and led him out on to the moor.”

The “curious [non-]incident” (i.e. one that really should have happened but failed to occur) is, according to this legal blog, the piece of Holmesian reasoning most often cited in court. [e.g. “Appellate Court of Connecticut cited in its recent opinion in State v. Rosado, 2012 WL 1003763 (Conn.App. 2012), to answer a hearsay question.”]

In lots of ways, noticing the absence of something is a trick that requires not only keen observation, but also a curiously un-Holmesian empathy for the rhythms, cycles, and sequences of human life. There are forensic voids (e.g. where a removed body covered a blood spatter pattern, as just about any viewer of CSI would know), but behavioural voids? Not so easy.

The Somerton Man

All of which brings me round to Australia’s curious incident of the Somerton Man. What would Sherlock Holmes have made of a death scene riddled with so many voids, so many geese that failed to cackle, so many dingoes that didn’t howl?

Naturally, the biggest absence is the lack of any identity, followed by a lack of a definitive cause of death (though the coroner put it that the death was not natural [Feltus, Ch.10]), along with a lack of any preceding timeline for the man. Beyond these ‘macro-absences’, however, there are numerous micro-absences, all of which would surely have been grist to Holmes’ mental mill:

* Overcoat but no hat

* Tickets (one used, one unused) but no money

* No wallet

* No ration card

* Absence of dirt on his shoes

* Absence of vomit on his clothes or on the beach (despite blood in his stomach)

A particular suitcase (that had been left at Adelaide Railway Station on the morning before the man’s death) then appeared as potential evidence. Once it had been strongly linked with the dead man (thanks to cotton thread), it offered an additional set of absences to puzzle over:

* No shoes (apart from the pair he was wearing)

* He had five ties but no socks (apart from the pair he was wearing)

* Air mail blank letters and six pencils but no inkpen or ink, and no received letters

* Identifying marks (“Kean”, “Keane”, “T Keane”) that led the police investigation nowhere

* Places where Labels attached to a shirt and to the suitcase itself (?) had been removed

* No medicine of any sort (yet the dead man had a significantly enlarged spleen, so one might expect him to have been to a doctor or hospital not long before)

I’ve previously blogged about the “T Keane” marks, arguing that these might well have been donated to charity following the death of local man Tom Keane in January 1947: and separately that the slippers (which were the wrong size for the dead man’s feet) and dressing gown may have been given to him by the local Mission to Seamen (Mrs John Morison was probably the Mission’s hospital visitor). But this is a thread that is hard to sustain further.

I have also blogged about the Somerton Man’s lack of socks, something which vexed Somerton Man blogger Pete Bowes several years back in a (now long-removed) series of posts. I once tried to link these with the rifle stock mysteriously left by young Fred Pruszinski on the beach in a suitcase with lots of socks. Derek Abbott in particular has long been fascinated by what story the absence of socks may be trying to tell us, so perhaps there are more pipes to be smoked before this is resolved.

No Vomit, Sherlock

If this was a setup for a Conan Doyle short story, Sherlock Holmes would surely have pointed out that because the lividity on the dead man’s neck was inconsistent with his position laid on the beach (regardless of alternative explanations Derek Abbott might construct) and there was no vomit at the scene, he most certainly did not die there. And while the absence of a wallet would normally line up with a robbery, the body’s was clearly not so much dumped on the beach as posed, cigarette carefully put in place.

All of which Holmes would no doubt class as wholly inconsistent with any suggestion that the person or persons who did that was/were random muggers. Rather, this was a person who died elsewhere (and who Holmes would perhaps speculate had been laid out horizontally on a small bed post mortem, with his head lolling backwards over the edge), and whose wallet and money (and indeed hat, it would seem) were all removed before being carried to the beach [Gerry Feltus’ “Final Twist” has an eye-witness to a man being carried onto the beach, Ch. 14].

Holmes’ next waypost would be the absence of dirt on the man’s shiny brown shoes: having left his shoe polish in his suitcase, he would surely have been unable to shine his shoes in the time between the morning and his death in the night. And so I think Holmes would triumphantly complete the story told by the lack of vomit: that in his convulsions prior to death, the dead man’s vomit had surely fallen on his hat and shoes, and that someone else – dare I say a woman, Watson? – had cleaned the shoes prior to the man’s being carried off to the beach for his final mise en scène. And though he had eaten a couple of hours before his death, there was no trace of his eating out (another behavioural void to account for): he must therefore have spent some time that evening in a house with a man and a woman, eating with one or both of them.

So: they must have known him, or else they would not have cleaned him up in the way they did: yet they must not have wanted to be linked to his death, for they attempted (unsuccessfully, it has to be said) to stage a mysterious-looking death scene for him, one that would have had no physical connection to them (a pursuit which they were more successful in).

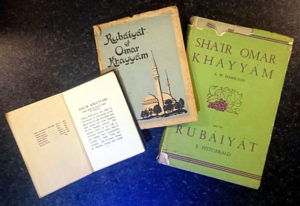

Did those people place the “Tamam Shud” scrap of paper in his fob pocket, as part of their dramatica staging? Holmes would surely think not: whatever its relation to the Rubaiyat allegedly found in the car around that time was, that was surely a separate story entirely, one quite unknown to them. And the car would form the centrepiece of an entirely separate chapter to Conan Doyle’s short story, one perhaps enough to tempt him to draw it out into a novella-sized accoun.

“The Case of the Missing Socks”

Finally, what of the missing socks? Sherlock Holmes would, I think, have first pointed out a sock-related mystery not previously noted elswehere: that even though the dead man’s suitcase had two pairs of Jockey underpants (one clean, one used) it contained not only no socks but no dirty socks either. In what circumstances would a man have dirty underwear but no dirty socks?

Hence once you have followed all the preceding Holmesian logic through, the three pipe problem that remains is this: why would someone walk around Glenelg with a pair of dirty socks, and not leave them in their suitcase back in Adelaide? Or, rather, why would someone travel with three pairs of underwear but only a single pair of socks?

For Holmes, the idea that the dead man would have carried anything around in smelly socks would be nonsensical. So I think the only conclusion the great fictional detective could have come to – having eliminated all he considered impossible – was that the dead man had arrived in Adelaide with something wrapped up in his spare pairs of socks in his suitcase – i.e. that he had brought spare socks with him, but that he was temporarily using them for a different purpose. He had therefore been able to change his underwear that morning but not his socks (because they were being used): moreover, Holmes would have said while tapping his pipe ash out, because the man was expecting to change into his spare socks later, he was without any doubt expecting to deliver what was wrapped up those socks to its destination during that day, and in doing so retrieve his socks.

But Holmes, Watson would ask, what was he carrying in those socks? Rolls of money, perhaps?

At this, Holmes would shake his head: my dear Watson, he would reply, this was not a man of money – his suitcase contents tell stories of ordinary life, of difficult times. He could not have been carrying anything bulky, or people would have noticed: it must have therefore been something valuable on the black market yet carryable beneath an overcoat on a train, bus or tram – and if so, why wrap it in socks for any reason apart from disguising its iconic shape? Hence, having eliminating all the impossible – as I so often do – the only object it can have possibly been was… a rifle fore-end.

My goodness, Holmes, Watson would reply, I do believe you have astounded me yet again. Derek Abbott was right: I shall have to call this The Case of the Missing Socks when I write it up in years to come. And… what of Fred Pruszinski?

What of him indeed, Watson…

“Whatever Remains…” (revisited)

From my perspective, I can see how Holmesian reasoning can almost be made to work: and I would argue that in the otherwise baffling case of the Somerton Man, the kind of short story reasoning I lay out above is just about as connected a positive account as can be genuinely fitted to the evidence. Had the Somerton Man brought something into Adelaide wrapped in his spare socks, expecting to deliver it during the day? It’s a good yarn, for sure, one that could easily be shoehorned into the Holmes and Watson canon. And, moreover, The Case of the Missing Socks does justice to pretty much every aspect of the case, both found and absent.

And yet, a small amount of prodding around the edges would surely display its many cracks and holes: it all remains no more than a story. We lack evidence: and ultimately it is evidence that persuades, evidence that proves, evidence that convicts. Reasoning from that which isn’t there and from that which did not occur all the way to that which did happen is a perilous argumentative tight-rope, a place surely only well-paid QCs and conspiracy theorists would feel comfortable balancing on.

As for me, I’m only comfortable writing this all up under cover of a Sherlock Holmes-themes blog post: but right now, perhaps building on a long series of absences to assemble this kind of novelistic take is as good as we can get. :-/