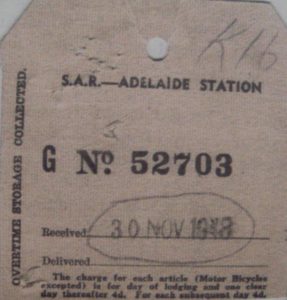

The “Somerton Man” gained his epithet from Somerton Beach near Adelaide, which was where his dead body was discovered in the early morning of 1st December 1948. Yet despite the mass of forensic evidence (his body and, more recently, an analysis of one of his hairs) and physical evidence (his clothes and possessions, plus his suitcase), his real identity has never been determined.

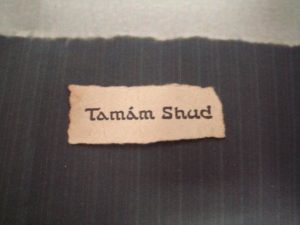

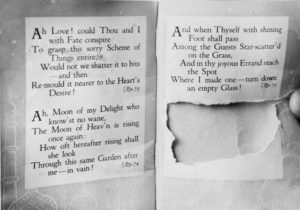

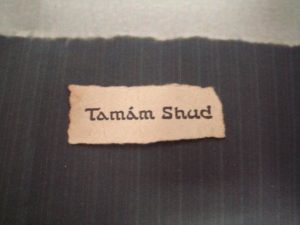

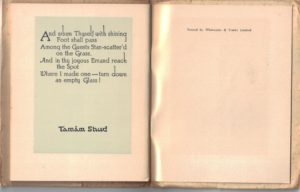

Police investigators were then led down into not so much a ‘rabbit hole’ as a labyrinthine warren of ‘twisty passages all alike’ by the tiniest of objects half-concealed in the man’s fob pocket… a tightly-furled slip of paper with the words “Tamam Shud” printed on it:

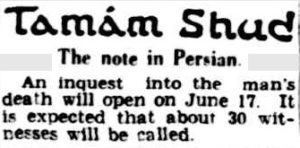

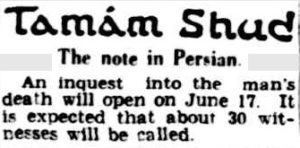

A cropped version of this appeared in the 9th June 1949 edition of the Adelaide Advertiser, just before the first Coronial inquest was due to start:

Police determined that these two words were Persian for “The End”; that they were the concluding piece of text in the Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam (a popular book of poetry at the time); and that they were printed in a font that was specific to the editions put out by Whitcombe and Tomb’s (a New Zealand publishing company).

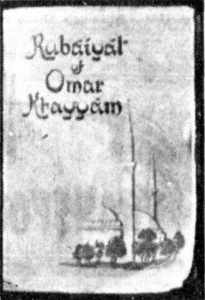

As a result, the police took the opportunity of the flurry of publicity surrounding the inquest to ask anyone in the general public to come forward if they just happened to have a copy of the specific edition of the Rubaiyat from which the final two printed words (“Tamam Shud”) had been ripped out by hand. A picture of the original Rubaiyat’s front cover appeared in the 26th July 1949 Adelaide News:

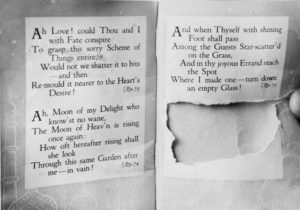

Amazingly, a Rubaiyat that exactly matched this description was quickly brought forward by a publicity-shy local “businessman”: it had been discovered in the back of his car parked in Jetty Road in Glenelg, not too far from the beach where the dead man’s body had been found. And when police photographers carefully examined indentations on the back of that (now long-lost) Rubaiyat, they uncovered not only something that looked like a mysterious code, but also one or more phone numbers (and possibly even a name, though this item remains completely unconfirmed).

What of these two wonderfully specific pieces of evidence? The code-like text was speedily passed to a top Australian code breaker (almost certainly Eric Nave), but proved indecryptible. As for the phone number(s), one led to a local nurse called Jo Thompson, who denied all knowledge of the Somerton Man when asked by the police (though we now know that she did know more than she said).

At the time, however, the code and the phone-numbers were the police’s two last-gasp hopes of cracking the mystery: and when those leads went cold, so too did the case. Despite all the wild and unfounded speculation (ranging all the way from romance and illegitimacy to Cold War espionage) that the decades since have seen, this is as much as we genuinely know… the rest is just guesswork (and often highly fanciful guesswork at that).

All the same, what these very public dead-ends did manage to achieve was to intensify the mystery surrounding the unidentified dead man on Somerton Beach. Who was he? Why was he there? How did he die? What had happened?

The Rubaiyat

One of the few non-speculative research avenues open to investigation is the Rubaiyat itself. What was its story? Where did it come from?

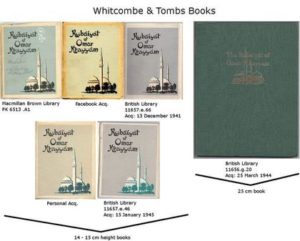

Retired detective Gerry Feltus, the man who (literally) wrote the book on the investigation into the Somerton Man cold case, spent years trying to find Whitcombe and Tomb’s editions of the Rubaiyat (as described in his Appendix 5). Here’s a picture of what he was looking for (note the highly ornate border):

After a great deal of searching, Feltus eventually managed to locate “two first edition copies”. One, however, “was printed in a different font and there was no ‘Tamam Shud’ at the end”, so was of no direct help to his search (p.168). The following is a scan of a different copy of this same particular edition:

Yet though the other copy Feltus found was a much better match, it too was not identical: the font and layout was the same, but the front cover was smaller and squarer than the image of the cover that appeared in the media at the time, while “the page positioning differed”. (p.169)

How could it be that Feltus’s years of diligent searching had produced a copy that was nearly-but-not-quite identical? What was going on?

Whitcombe and Tomb’s

Founded in 1888 in New Zealand, Whitcombe and Tomb’s (now merged and reborn as “Whitcoulls”) was by 1948 something of an institution: it printed text books and all manner of serious-minded stuff. Here’s a photo of its Dunedin store in 1931 (which I found here):

But as WWII approached, W&T was struggling to find an edge over its many rivals: it was perceived as being staid and somewhat boring, while its competitors were building up reputations for having a stylistic edge over W&T.

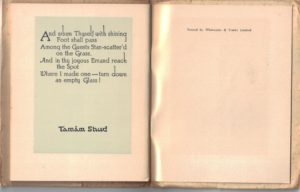

If you look again at the edition above, I think you can see W&T’s inner bore emerging: even though it uses a nice enough font, overall the pages themselves are rather dull-looking – though professional, it’s completely unremarkable. The final page states:

By way of comparison, the other edition not only has a highly-decorated border on every page, it finishes with a triangular design that stresses the artistry involved in the new production – that it is “A W&T Art Production“:

Something seems to have changed…

Rubaiyat Advertisements

I suspect we can learn a lot more from the press advertisements the company took out to try to sell its Rubaiyats.

The sequence of advertisements in New Zealand Papers Past (a Kiwi version of Trove) starts with a 24th December 1936 W&T advert for a Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam at 4/6. However, I’m not sure what to make of it.

Papers Past then has the following advert from 22nd November 1941:

Pretty Booklets

The Courage and Friendship Booklets, produced by Messrs Whitcombe and Tombs Ltd. (Auckland), are enveloped ready for post, a very attractive means of conveying a Christmas greeting, The five titles issued are Bracken’s Not Understood, Fitzgerald’s translation of the Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam, some songs and poems of Robert Burns gathered as Sprigs o’ Heather, an anthology of Great Thoughts from famous books, and Golden Threads drawn from Trine’s “In Tune with the Infinite.” The booklets are prettily designed, two being printed in a decorative letter.

According to this November 1941 advert, these booklets were priced at 1/6 (or 1/7 posted). The posted price went up to 1/8 in 1943, when a sixth title was added to the list (“Falling Leaves, thoughts for shadowed days”).

However, an advert from 22nd April 1944 announced a new – and much more upmarket – edition:

OMAR KHAYYAM

Delight again and again over, this wise old Persian’s verses; you can never exhaust their pleasures: they carry you far beyond the four walls of everyday life – singing with sheer beauty of love, and life’s riches – The Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam. New edition bound in dark green cloth, with illustration. 12/6

21st December 1944 saw them advertising their cheaper (1/6) Courage and Friendship version, and now with “Merrie England, songs from Shakespeare” (a seventh title) added to the list.

Similarly, the following year (29th November 1945) saw them selling the same series at 1/6, but this time with “Forget-me-nots, an anthology of friendship” (an eighth title) added to the list.

Trove aficionados can also find Australian adverts, e.g. for the Courage and Friendship series:

* 5th December 1942 (Courage And Friendship, 5 titles, 1/6 each, 1/8 posted)

Once you get to 1944, the second luxury edition appears on sale in Australia:

* 22nd January 1944 8/6, 8/10 posted

* 26th January 1944 8/6, 8/10 posted

And then there’s a third leatherette-bound W&T Rubaiyat we’re not otherwise aware of:

21st December 1946 and 25th December 1946: “THE RUBAIYAT OF OMAR KHAYYAM. A delightful leatherette-bound volume, suitable for presentation. Price, 5/6 (posted 5/8).”

And is this 1947 version the same as the Courage And Friendship edition, but at a slightly higher price?

* 3rd May 1947 “RUBAIYAT OF OMAR KHAYYAM 2/5. Postage, 2d. A compact, well illustrated edition of this evergreen classic”.

This 1947 version sounds like the 1944 luxury edition again:

* 27th September 1947 “RUBAIYAT OF OMAR KHAYYAM, Large gift edition, beautifully illustrated. A Whitcombe and Tombs art production. 8/6. (Posted 8/10.)”

As for this 1948 mid-price version, I’m guessing that this was the Rubaiyat published in London by Frederick Muller Ltd, because George Buday (1907-1990) was an artist and printmaker who emigrated to Britain from Hungary in 1937, and ended up living in Coulsdon (ten miles from Surbiton):

* 27th March 1948 “RUBAIYAT OF OMAR KHAYYAM. 3/2, postage 3d. An attractive little gift book, Illustrated with engravings by George Buday.”

So Many Rubaiyats, So Little Time!

Even though I have tried to collect as many of the Whitcombe and Tomb’s advertisements together as I can, I think it should (“Shud”?) be clear that it would take a far more determined book detective to reconstruct the exact sequence of books being published here.

The dull-looking “Printed by Whitcombe and Tombs” edition that Gerry Feltus found might conceivably be the 1936 Rubaiyat: or it might just as well be a very early version of the Courage and Friendship series.

Regardless, it seems to me that we can reduce most of Whitcombe and Tomb’s Rubaiyats into two basic families:

(1) the smaller and more compact, Courage & Friendship pocket Rubaiyats (low-end, cheap stuff for gifts)

(2) the taller and generally fancier deluxe presentation Rubaiyats (high-end, 5+ times more expensive!)

Moreover, from other stuff (to come in a follow-up post), it seems that the Courage & Friendship pocket Rubaiyats were reprinted in slightly different colours from year to year, both inside and out. For example, the decorative page borders were cream in one year and beige in the next, while the border blocked around the text was green in one edition and yellow in another. And the inside page of the front cover was reprinted at different times, because different Courage and Friendship Rubaiyats list different numbers of titles in the C&F range.

So it seems to me that if only a picture had been taken of the inside cover of the Somerton Man’s Rubaiyat, we’d be able to date it simply by the number of other Courage and Friendship titles listed in the same series. But perhaps there’s a note still in the police file somewhere.

Courage and Friendship Covers

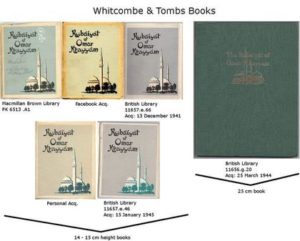

The very nice “An Empty Glass” Somerton Man Wiki has rather splendidly managed to somehow collect a sequence of Whitcombe and Tomb’s Rubaiyat front covers in its page on the Somerton Man’s Rubaiyat.

Its key picture looks like this:

Here you can see different printing colour schemes being used in different years: and the substantial difference between the (compact) Courage and Friendship editions on the left and the deluxe version on the right.

So, What Is Going On, Nick?

I think it’s reasonably simple. What Whitcombe and Tomb’s were doing with the Rubaiyat was dipping their corporate toes into the oversize paddling pool of design aesthetics: which is why they tried different price-points, different materials, different techniques, different sizes, etc. By and large, it seems to have been an experimental time for them.

Each Courage and Friendship printing batch seems to have had its cover printed in a different colour: if only we had a record of the list of other Courage and Friendship books in the series that appeared on the front inside flap of the cover of the Somerton Man’s book, we would be able to tell which year it had been printed.

Gerry Feltus had found the right book: just not the right year’s edition of that book, it would seem. And the reason that there was so much year-to-year variability is simply because Whitcombe and Tomb’s was trying to extricate itself from the staid, boring corner of the market it had painted itself into so relentlessly for so many years. Even though it wanted to develop its arty side, it didn’t really know what was going to work in the wider book-buying market. (Frankly, it seems to me that it never quite managed this particular trick).

And so we have reached our almost-paradoxical conclusion of the day: that even though Whitcombe and Tomb’s deluxe version of the Rubaiyat (with its gilt lettering or hand-stitched lettering) would be a more desirable book to own from the point of view of a collector, it is very probably from the far more cheap-and-cheerful 1/6 Courage and Friendship edition that the Somerton Man had ripped out his “Tamam Shud”.

And quite why he did that at all is another matter entirely! 😐