The news of the moment is that Australian Attorney-General John Rau has refused Professor Derek Abbott’s request that the Somerton man’s body be exhumed for DNA / autosome testing, commenting that Abbott’s application wasn’t “compelling”. Well, I guess that means we’re going to have to do it the hard way, then… 🙂

So here (as long-promised) is Part One of my thoughts on the Unknown Man and his mysterious cipher note, perhaps they’ll open up some new research avenues. Overall, while I’m pretty sure my reasoning is basically sound, please feel free to disagree! (PS: I’ve included a few page references to Gerry Feltus’ book for Klaus Schmeh and other hardcore cipher mystery buffs).

[For background on the Somerton Man / Unknown Man / Taman Shud / Tamam Shud case, here’s a pair of links that should get you started]

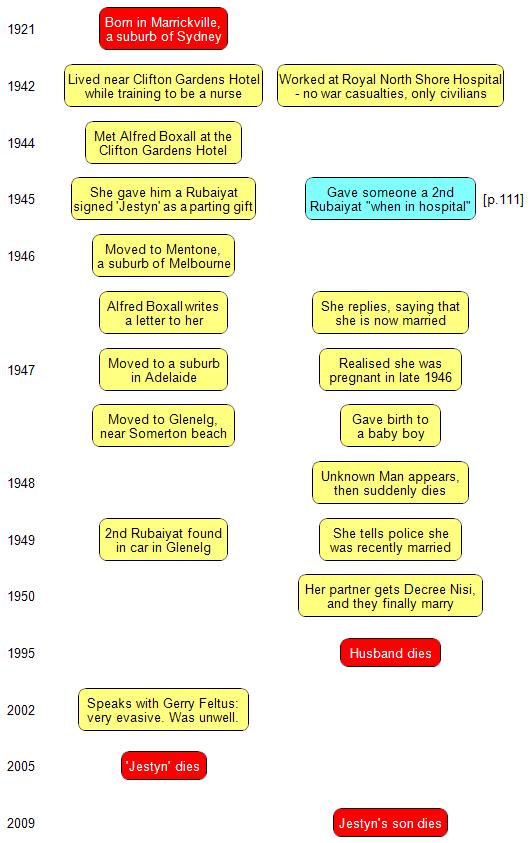

(1) Why was the Unknown Man in Somerton? As with pretty much all historical mysteries, it is ‘within the realms of possibility’ that all the evidence that the police were (eventually) able to assemble had been consciously constructed and arranged to give a certain impression, and that the real story behind them all was entirely different. Yet while we should acknowledge that each individual piece of evidence might well have been influenced, finessed, modified or even faked, we should be trying to look through them to the overall narrative. So, I view as basically reliable the link between the Unknown Man and the copy of Taman Shud subsequently found nearby – and hence between the Unknown Man and the nurse ‘Jestyn’, whose private phone number was written in the back, and who lived close to Somerton Beach in Glenelg.

Given that a man was seen knocking at Jestyn’s door during the day before the Unknown Man’s appearance on the beach, it seems to me a wholly unremarkable conclusion that the Unknown Man almost certainly came to Glenelg specifically to visit her. Moreover, Jestyn had not long lived in Glenelg, so had had that phone number for only a short time: and must therefore have given the Unknown Man her phone number relatively recently.

(2) Where did the Unknown Man die? I think the answer – without a shadow of a doubt – is “not on the beach“. He was found propped up on Somerton beach yet with “lividity above the neck and ears” [p.204] – i.e blood pooled at the back of his head after death. If he had quietly died in the position in which he was subsequently found, gravity would have pushed his blood to his feet: hence I conclude that he died somewhere else entirely, where in fact his body was left for a while with his head below the rest of his body, before being carried to the beach and arranged in that oddly casual pose.

Moreover, Somerton Beach is sandy – so if the Unknown Man had lain on that beach for any period of time with his head at its lowest point before being physically rearranged by a random passer-by, there would surely have been sand in his hair… but there was none. As such, I disagree with the Coroner T.E.Erskine who concluded that “He died on the shore at Somerton on the 1st December, 1948.” [p.205] – rather, though the man was found dead there, I find it highly unlikely that it was the scene of his death.

No: to my mind, the only realistic scenario is the Unknown Man died somewhere else entirely and was carried to the beach – probably, from his weight, by a man. The report mentioned by Gerry Feltus [pp.143-144] of someone seen apparently doing exactly this around 10pm on the previous evening would seem to be entirely consistent with this scenario.

(3) How did the Unknown Man die? The first pathologist noted that the man was in good physical shape, and that his “heart was of normal size, and normal in every way”. There was blood in his stomach along with the remains of a pasty eaten roughly three hours before his death.

Though his spleen was significantly enlarged (3x times normal size) AKA splenomegaly, note that this is most likely a symptom of a different problem rather than the problem itself. As I understand it, your spleen can’t suddenly enlarge in a matter of a day: and given that the Unknown Man was apparently only in Somerton for less than a day, he must have arrived there with his spleen already enlarged. The lack of any obvious signs of another problem points to a problem that had just receded, quite probably a recent viral infection. So to me, the presence of an enlarged spleen implies that the Unknown Man had only just recovered from an significant illness, and that he was perhaps still in quite a fragile state. He would very probably have also had some lingering discomfort or back pain from his enlarged spleen.

(4) What was the cause of the Unknown Man’s death? It’s important to remember that coroners and pathologists repeatedly examined his body and screened his blood, looking for any faint clue that might help to narrow down the cause of his death, but with no success. Given the healthy state of his heart, the two best theories left standing (in my opinion) are (a) a deviously hard-to-pin-down poison deliberately administered either by himself or by someone else but which quickly disappeared from his system after death; or (b) an unexpectedly strong allergic reaction to something he had ingested, with the most notable candidate being excess sulphur dioxide used as a preservative in the pasty, which in 1948 was yet to be controlled [pp.202-203].

For me, I have to say that there is only one likely scenario I’m at all comfortable with: that while at Jestyn’s house late that afternoon, he had an unexpectedly strong allergic reaction to something in the pasty he had had for lunch (for why else would there be blood in his stomach?) In my mind, he must have laid down on a bed suffering from acute stomach cramps; but because he was so weakened by his recent illness, he unfortunately died as a result of his reaction, slumping with his head falling backwards over the edge of the bed – not upside down, but with his neck supported at an angle by the edge of the bed, leading to the distinctive lividity observed by the pathologist.

Even though Jestyn had worked as a nurse (and more on that later), I suspect she was not physically strong enough to move him from that position, so left him just as he was until her husband arrived home in the evening. I believe the Unknown Man remained on the bed until later that evening, when they carried him to the beach to pose him there, to be found in the morning.

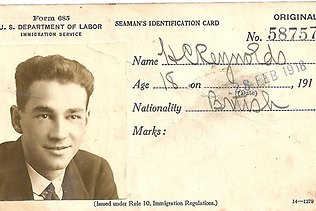

(5) What was the Unknown Man’s personal situation? In his modest suitcase, there were stencilling tools for making signs such as Third Officers use on ships to mark baggage and crates, along with the princely sum of sixpence. It was December (the middle of the Australian summer), and his body had the remains of the kind of outdoor tan you’d expect from someone who had worked outside the previous summer, but not that summer. His clothes came from a variety of places, and in a variety of sizes (his slippers were smaller than his shoes), and most had their labels removed. The items that did have a label were marked “T. Kean” or “T. Keane”.

This has led to a lot of spy theories (“an international man of mystery who didn’t want to be identified“, etc) and conspiracy theories (“his killers removed the labels from his clothes in order to conceal his identity“, etc), none of which rings true at all to me. For me, however, the simplest explanation by a mile was simply that he was poor (if not actually destitute), and had been given these clothes by a charity. The original owners’ name tags would have been removed by the charity before being given to the needy.

Furthermore, given the probable connection with sea-faring implied by the stencilling tools in his case, my prediction is that he was given these clothes by a local Mission to Seafarers or Stella Maris branch.

So: as far as I can see, the most likely overall scenario is that the Unknown Man had recently had a serious viral infection, travelled to see Jestyn in Glenelg, had a pasty for lunch, was taken ill with an allergic reaction, died on her bed, but was posed on Somerton beach that night. But… why was he there at all, and what of his mysterious enciphered note? More on that in Part Two…