In a comment here yesterday, the ever-insightful Byron Deveson raised once again the possibility that the half-a-rifle-in-the-suitcase-with-socks case might be connected with the Somerton-Man-with-no-socks-in-his-suitcase case. Put like that, you have to admit that there is a certain harmonious balance to the suggestion. 🙂

Though the Somerton Man case we already know (often in painstaking detail), the other case hasn’t yet really been explored in great depth: as for me, until yesterday I thought it would prove to be no more than a crime of opportunity. But I have now built up a very detailed scenario of what really happened there and why – and to my surprise, it (if true) would seem to explain precisely why the Somerton Man was in Glenelg.

The Evidence

The Advertiser Monday 29th November 1948 Page 6

Mystery Somerton Find

The discovery near the water’s edge at Somerton yesterday of a man’s three-piece suit, sports trousers, a shoe, several pairs of socks and an overcoat is being investigated by police. With the clothing was a rifle stock without a barrel. The articles appeared to have been in the water for some time.

Barrier Miner (Broken Hill) 29th November 1948 page 1

Hectic Week End For B. Hill Boy.

Adelaide. – During a hectic week-end a 17-year-old Broken Hill boy is alleged to have stolen a motor cycle from Broken Hill on Friday night and ridden it to Adelaide, abandoned the cycle in the sandhills at Glenelg, dumped a suitcase containing clothing and a rifle at Somerton beach, and illegally used a motor car at Port Noarlunga.

The lad told the police that he had dumped the clothes, which were found at Somerton yesterday.

Police found the clothes and a rifle with the barrel missing, but the youth said he had left them in the suitcase. He said he walked to Port Noarlunga, where he was later arrested for allegedly having illegal use of a motor car. He appeared in the Juvenile Court today and was remanded until tomorrow week.

The Advertiser 30th November 1948 page 6

ADELAIDE JUVENILE BEFORE MR B. J. COOMBE. SM. Charge Against Youth.— Stated by the prosecution to have run away from his home in NSW, a youth of 17 was charged yesterday with having, at Port Noarlunga on Sunday, unlawfully used a motor car belonging to Maxwell John McCormack, second-hand dealer, of Stanley street North Adelaide. Prosecuting, APP Northwood said that, shortly after the disappearance of the car had been reported to the police, the youth was stopped while he was driving it along the South road. When questioned by traffic constables he admitted the offence. Defendant was remanded in custody until December 7.

Yesterday, I found out from Trove exactly whose motorbike it was: a Mr W. H. Coffey of 637 Lane Lane. Coffey initially reported that his motorbike had been stolen during the evening of Friday 26th November 1948 at some time before 12.30am, when his shift at the Central Power Station finished. The bike was later seen by police passing through Mannahill (89 miles SW of Broken Hill), halfway down the Barrier Highway and heading in the direction of Adelaide.

The Timeline

So: the unnamed youth…

* stole a motorbike from outside the Central Power Station in Broken Hill

* used it to carry a suitcase (containing a rifle and men’s clothes) hundreds of miles to south of Adelaide

* left the suitcase on Somerton Beach

* dumped the bike in the sand dunes at Glenelg

* walked 12 or so miles to Port Noarlunga

* stole a car and headed North back past Glenelg towards Western Adelaide

* was captured by police on South Road

On reflection, I’m now completely happy to rule out the notion that this whole thing was some kind of opportunistic joy-ride. But if not that, what actually happened to connect all these scattered pieces of evidence?

The Rifle Sock Scenario

Right now, I can only see a single scenario that joins all these dots… and it goes like this.

(1) Someone near Somerton Beach wants to buy a rifle, and someone in Broken Hill wants to sell a stolen rifle. This is what drives this entire scenario: everything else clicks through as a sort of logical consequence of this shady buyer-seller attempted transaction… though, as we shall see, with an unfortunate twist.

(2) The seller’s first challenge is how to get the stolen rifle from Broken Hill to Somerton Beach without carrying it himself. He finds a do-anything 17-year-old kid who’s willing to steal a motorbike and be the courier.

(3) The seller’s second challenge is how to fit (and hide) the rifle inside a suitcase. He separates the rifle barrel from the rifle stock, and uses socks to cover up the four exposed ends, to stop the two bumping noisily around in the suitcase. He then wraps them up inside a suit and an overcoat: anyone opening that suitcase would see, well, a suit inside a case. Which is what suitcases are for.

(4) The seller’s third challenge is how to make sure the suitcase’s contents wouldn’t lead straight back to him if it fell into the wrong hands. He removes all the labels from the clothes: a mechanism already eerily familiar to almost everyone who has read about the Somerton Man case.

(5) The seller’s fourth challenge is how to get the rifle from the courier to the buyer without having the courier knowing the buyer’s name or address. His answer is to tell the courier to drop the suitcase in a certain place on Somerton Beach at a certain time, presumably near to where the buyer lives or works.

(6) The plan, then, is for the buyer to collect the suitcase with the rifle in from the beach, whereupon everything is where it needs to be (apart from payment… but more on that later).

Yet even though all six steps appear to have happened exactly as they were supposed to, the suitcase should not have ended up dumped in the sea at Somerton Beach with half a rifle in: so something clearly went very wrong indeed. But what?

How Did Such a Perfect Plan Go Wrong?

Again, I can only think of a single scenario that fits and yet explains everything we see.

(7) Before leaving the beach, the buyer decides to check the contents, and discovers that the seller omitted to describe something about the rifle stock that made it completely unusable.

For example: it was a left-handed rifle stock. Or if not that, then some other utterly fundamental aspect of the rifle stock that was sufficient to destroy the viability of the whole transaction.

Whatever the precise reason, the buyer is now so mortally offended by the rifle stock that he puts it back inside the suitcase, pockets the rifle barrel, and – still in a rage – throws the suitcase and its contents into the sea, before marching off. The rifle is unusable, the deal is off: and from now on, all outcomes are possible.

How Does This Fit With The Somerton Man?

If the seller just happened to be the Somerton Man and the buyer just happened to be Prosper McTaggart Thomson (AKA George Thomson), then what happened next surely began with the remainder of the plan that they had previously agreed.

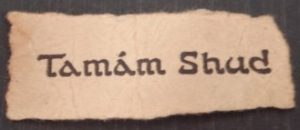

(8) The seller travels down to Adelaide on the train, and makes his way to Somerton to collect his suitcase, clothes, and payment for the rifle. With him he has a wartime knock-off copy of the Rubaiyat: written on its soft back-cover is Jessie’s Somerton telephone number X3239 (the one that Prosper used in his advertisements).

(9) When the seller arrives, he finds Thomson won’t pay him for the rifle. He launches himself angrily at George, but the younger man is fitter and faster: all the older man manages to do is scratch his hand. He asks for his suitcase: Prosper tells him he left it on the beach – neither realises that it has been found and mentioned in the Advertiser.

(10) Somehow the seller dies…

It seems both to Byron Deveson and to me that the Somerton Man had seen his levels of lead drop down in previous weeks, suggesting that he had previously had a high level of exposure to lead (probably occupational rather than just residential, and probably from lead in its powder form rather than in ingot form), but in the previous few weeks had changed his working environment. His spleen was enlarged, implying that he was fundamentally unwell: if he was sitting on the beach unwell, without money, feeling double-crossed, he could simply have died of stress.

Though pretty much any other outcome is possible, too. 🙁

The Punchline

Even when I first dreamed up the whole rifle sock scenario, I found it hard to believe: it seemed such a gossamer web of double-dealing and interstate shadiness. What, really, are the odds that the Somerton Man was selling a left-handed rifle to Prosper Thomson?

Might the Rubaiyat code simply contain directions (somehow) to help the Somerton Man get to Somerton from Adelaide?

Anyway, I’ll let Byron Deveson have the last word here, for he uncovered a piece of evidence from 1949 that perhaps ices the whole fishy cake:-

Prosper advertised for a particular type of rifle in June 1949. To me, advertising for a particular model smells fishy and suggests that Prosper was setting up an alibi in case he was ever found with the rifle that had been dumped on Somerton beach.

The Advertiser 18 June 1949 Page 17

RIFLE, automatic Winchester, model 63 or similar, for cash. Thomson 90A Moseley st., Glenelg. X3239.

What Next?

I’ve gone through all the Law Courts reports in the Advertiser for December 1948, and there seems to have been no follow-up report. But perhaps it would be worth looking at the Court files for 1948, to see if anything else is mentioned there, however small. Specificially, “GRG3/10 Court files – Adelaide Local Court” which covers from 1948 to 1970, and is held by the State Records of South Australia:-

“This series comrpises three seperate sequences of files maintained by the Adelaide Local Court from 1948 to 1970.

– Court files, annual single number, 1948 – 1970

– Australian Register of Judgement files, annual single number with ‘ARJ’ prefix, 1949 – 1968

– Register of Transferred Judgement files, annual single number with ‘RTJ’ prefix, 1948 – 1968

423 metres.”

Any ideas as to how we can identify this 17-year-old lad from Broken Hill? He may still be alive – if this scenario is right, he probably met the Somerton Man. What might he say?