It is a sad truth that almost all we know about the Somerton Man case was known to the police by the end of 1949. However, a shining exception to this 65-year-old evidential stasis is the set of spectrometry measurements taken by some of Derek Abbott’s students in 2013. Cunningly, their subject matter was a short hair embedded in the plaster cast of the dead man (the one in the SAPOL museum): progressively burning this hair with a laser gave them spectrometric readings of the physical chemistry going on in the Somerton Man’s body very late in his life.

On the positive side, it turned out that the hair included a root, so its timeline is almost certain to cover the interesting days right up to his death. However, it is only a very short hair, so it only really gives us hints about what was happening in roughly his final fortnight.

Intriguingly, I found out this week that a new cohort of Derek Abbott’s students has recently repeated this experiment, but with a substantially longer hair. Unfortunately this second hair did not include a root, which makes calibrating the results more difficult: and the results and analysis have not yet been released.

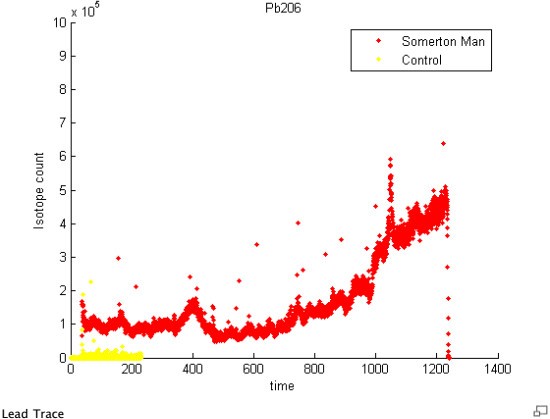

What of the first set of results? Of all the different isotopes the students detected and graphed, one stands out very strongly: lead. (Note that the graph is time-reversed, with the root end at the left and the older end at the right.)

In a post a few months back, Gordon Cramer suggested that this lead might suggest a connection with the nearby Port Pirie, where there was a huge lead smelting works. Though he then went on to assert that the connection to the Somerton Man probably wasn’t to do with the lead as such, but was surely some kind of spy-related thing to do with uranium processing (which was also close to Port Pirie, and was just starting up in 1947/1948). But as always, Gordon is free to go off in any direction he chooses.

As for me, I’m far more concerned with the lead itself, and what its possible relationship with Port Pirie might be. Derek Abbott rightly cautions that we don’t really know what was considered a normal level of environmental lead in Adelaide in 1948 (and so we should be careful about what inferences we draw from the lead graph): but I often think that a small detail can tell its own story, and this unexpected lead trace might well be such an instance.

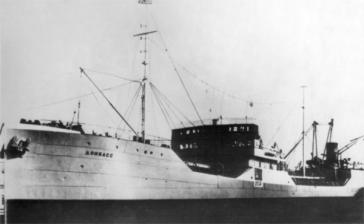

I’ve said before that I suspect that the Somerton Man was an overseas merchant seaman, quite probably a Third Officer with responsibility for lading and stencilling details on crates and boxes as they were stacked in a ship’s hold. At the same time, the primary way that lead left Port Pirie was by the ton, stacked into ships’ holds: as we shall see in a different post in a few days’ time, ships once loaded with lead then often travelled the 139 miles south to Port Adelaide where additional bales of wool and leather were taken on: and then finally the ship left South Australian waters for its final destination (wherever in the world that happened to be).

The Port Pirie Recorder from this period included a shipping news column (“Pirie Shipping News”), detailing arrivals, loadings and departures at the port. If we collate all this together solely for lead shipments in November 1948, this is what we find:

Arr Dep

8 – 10 Clan Maclean (2500 tons) – for United Kingdom via Port Adelaide (Gibbs, Bright & Co)

10 – 12 Ericbank (2250 tons) – for United Kingdom (Howard Smith Ltd)

11 – 13 Annam (1200 tons) – for Marseilles via Port Adelaide (Gibbs, Bright & Co)

15 – 17 American Producer (1200 tons) – for New York via Port Adelaide (Dalgety & Co. Ltd)

16 – 18 City of Delhi (2500 tons) – for United Kingdom (Elder, Smith & Co. Ltd)

18 – 20 Lanarkshire (1000 tons) – for United Kingdom (Gibbs, Bright & Co)

25 – 30 Corio (2800 tons) – for Sydney (Howard Smith Ltd)

So, what might the lead timeline be telling us? I think that if the Somerton Man was a Third Officer lading and marking up crates of lead, with a substantial spike roughly two weeks before his death in the night of 30th November 1948, then there would seem to be a good chance we can narrow down the number of boats he was working on to three or perhaps five: American Producer, City of Delhi, Lanarkshire, and possibly Annam or Ericbank.

Frustratingly, NAA: D458 Volume I (the ledger of “seamen engaged, discharged, deserted or died at Port Pirie”) only runs to 31st March 1948, which is a bit of a shame. However, there is a very substantial body (15.48 linear metres!) of archives for crew data in Adelaide in NAA record D3064:-

This series comprises lists of ships crews who visited Port Adelaide and outports.

The series basically comprises Form M + S 11(attachment) and supporting documentation. Currently documents are arranged in chronological order in calendar year blocks.

Information contained in these documents includes names, dates and places of birth, nationalities, some information regarding desertions, restricted crew members on board, crew changes, last and next port of call for ship, animal and birds on board.

So if I’m right about the story the lead timeline seems to be telling us, then anyone who wants to be the first to see the Somerton Man’s name for themselves should go to the SA archives at great speed and have a look at the D3064 (November 1948) crew lists for these ships (they’re not available online), particularly where there’s any difference between the crew that arrived and the crew that left.

Any takers? 🙂