I’ll start with a quick Somerton Man announcement: Professor Derek Abbott will be doing an interactive AMA session on Reddit right at the end of this month (August 2014), which will happen at the following times:-

– Eastern Standard Time: Saturday, 30 August 2014 at 9:00:00 p.m

– Mountain Daylight Time: Saturday, 30 August 2014 at 7:00:00 p.m

– Pacific Standard Time: Saturday, 30 August 2014 at 6:00:00 p.m

– Australian Central Standard Time: Sunday, 31 August 2014 at 10:30:00 a.m

– Australian Western Standard Time: Sunday, 31 August 2014 at 9:00:00 a.m

– New Zealand Standard Time: Sunday, 31 August 2014 at 1:00:00 p.m

– Central European Summer Time: Sunday, 31 August 2014 at 3:00:00 a.m

– British Summer Time: Sunday, 31 August 2014 at 2:00:00 a.m

If you have Tamam Shud questions for him that have long been burning into your soul, perhaps that would be a good time and place to ask them.

Today’s post is about something oddly specific: what the South Australian police apparently didn’t find.

If we assume, quite reasonably, that the Somerton Man was the owner of the suitcase found at Adelaide railway station not long after his death, we end up with some curious gaps – a “missing list” of things that ought to be present but were not.

At his death, what he had on him was:

* 1 jacket

* 1 shirt

* 1 tie.

* 1 pullover (even though it was the middle of the hot Australian winter)

* 1 pair of trousers (made of Crusader Cloth)

* 1 singlet

* 1 pair of jockey underpants

* 1 pair of socks

* 1 pair of shoes (new-looking)

* 1 Army Club cigarette packet (containing cheaper Kensitas cigarettes)

* 1 quarter-full box of matches (Bryant and May)

* 1 half-full packet of chewing gum (Juicy Fruit)

* 2 combs

* 1 piece of rolled-up paper (famously bearing the words “Tamam Shud”)

* 1 used bus ticket to Glenelg

* 1 unused second-class rail ticket to Henley Beach.

Here are the contents of the stuff that was found in the (also new-looking) suitcase:-

Clothes

* 1 laundry bag (marked “Keane”)

* 4 ties (one marked “Kean”)

* 2 singlets (one marked “Kean”, the other with name tag torn off)

* 2 pairs of underpants

* 1 pair of slippers (size 8)

* 1 pair of trousers (‘Marco’ brand)

* 1 sports coat

* 1 yellow coat shirt

* 1 coat shirt

* 1 shirt (name tag removed)

* 1 scarf

* 6 handkerchiefs

* 1 dressing gown and cord

* 1 pair of pyjamas

Clothes accessories

* 2 coat hangers

* 1 front stud

* 1 back stud

* 1 button (brown)

* 3 safety pins

* 1 card of tan thread

* 1 tin of tan boot polish (Kiwi)

Work tools (it would seem)

* 1 scissors in sheath

* 1 knife in sheath

* 1 stencil brush

* 1 piece of light board (zinc?)

* 1 small screwdriver

* 1 pair of broken scissors

* 1 loupe (small ring shaped object)

Personal hygiene

* 1 razor strop

* 1 razor

* 1 shaving brush

* 1 toothbrush and toothpaste

* 1 soap dish (apparently green)

Correspondence

* 8 large and 1 small envelopes

* 6 pencils

* 2 air-mail stickers

* 1 rubber

Miscellaneous stuff

* 1 hairpin (in the soap dish)

* 1 piece light cord

* 1 cigarette lighter

* 1 6d coin (in the trouser pocket)

* 1 tea spoon

* 1 glass dish

Put all these pieces together, and you get a surprisingly long list of things that weren’t there:-

* Hat

* Outer coat

* Pen (or did he really write everything in pencil?)

* Money

* Ration card

* Identity card

* Wallet

* Socks

* Any kind of railway ticket (if he came to Adelaide by train)

* Any letters received

Were these all lost (in a bet in a pub?), dropped (in a fight in the street?), stolen (by strappers on the beach?), removed (by a spying clean-up crew?), or what? Nobody knows – not even Derek Abbott. It’s a first-class mystery, for sure.

What does it all mean?

Well… that’s the big question, isn’t it?

It’s certainly odd that the Somerton Man seems to have only owned a single pair of socks. I’ve wondered (elsewhere) whether he might have used his other socks to wrap his money in, and whether he had those socks in his outer coat’s pockets. I’m well aware that this, as explanations go, is both plausible and ridiculous at the same time… but if you have a better explanation, please say.

I think the absence of letters may also be telling. I feel reasonably sure that the Somerton Man had letters in his possession, but carried them in his pocket because at least one of them included the address he was travelling to.

I also suspect that the “T Kean[e]” was Adelaide Freemason Tom Kean, whose 1947 Will – I believe, but can’t prove – donated many of his clothes to a local charity, from where the Somerton Man received it.

But I think that perhaps the biggest clue of all in his possessions has yet to be properly mentioned by anyone – the dressing gown and slippers. I recently read a short “Out Among The People” article in Trove from the 7th November 1950 edition of the Adelaide ‘Tizer, which said that the Mission To Seamen visited sick seamen in hospital and supplied them with “cigarettes, fruit, toilet necessities, slippers, books, dressing gowns…”

The full extract goes like this:-

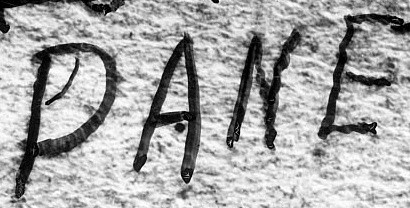

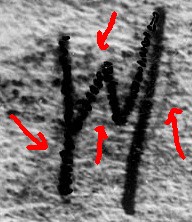

Missions To Seamen

In addition to providing wholesome entertainment for crews of visiting vessels at the Flying Angels at Port Adelaide and Outer Harbor, the Missions to Seamen also watches their interests if they are sick in hospital. A member of the committee cited cases in an enlightening account to me yesterday. “One patient, an Irish lad, has been in hospital for 3 1/2 years and recently was permitted to get up for the first time.” she said. “The hospital visitor has seen him regularly and has been able to do the manv little things his own family would have done in the way of shopping, business affairs, arranging for a wireless set, and so on. A young South African suffering from polio was visited daily and helped in his efforts to walk again in the hospital grounds in the evening. Just recently patients have been Swedish, Indian, Cornish, Scotch, English and Irish. An Indian from Pakistan has been in hospital for 20 weeks, and will soon undergo another operation.”

Devoted Nurses

My committee friend described the devotion of the nursing staff to these lonely overseas patients as wonderful. The Mission supplied cigarettes, fruit, toilet necessities, slippers, books, dressing gowns, had their laundry done when necessary; in fact, it did as far as possible take the place of the patient’s family. The men are most grateful and say they do not know what they would do without this thought and care. “I have been receiving letters from at least 10 former patients regularly for the past three years,” she told me. “Short motor drives and visits to private homes are arranged when, patients can get their doctor’s permission to do so. Two seamen were taken out and home to tea this week-end.”

Hmmm… I wonder who that female committee member was?

The simplest explanation of all?

Prediction #1: the Somerton Man was a foreign merchant seaman in Adelaide who had been taken seriously ill at sea, and had been visited in hospital by the Mission to Seamen. He was a Third Officer (hence his stencilling equipment for marking cargo.). He had written letters home overseas (hence the air mail stickers).

Prediction #2: the Somerton Man was Russian and needed an interpreter to help him get effective treatment. The nurse we know as “Jestyn” (who, we are now told, spoke Russian when she was younger) was asked in by the Mission for Seamen as a Russian-speaking volunteer – what we might nowadays call a ‘patient advocate’.

Prediction #3: the Somerton Man wrote letters to her in Russian from the hospital and sent them to her home address in Glenelg; and that she wrote back to him. This was a source of great comfort to him.

Prediction #4: the Somerton Man didn’t arrive in Adelaide from Melbourne, but was already in hospital there. Feeling terribly unwell and alone he decided to discharge himself from hospital and go and visit her in Glenelg. He put his possessions into a suitcase given to him by the Mission To Seamen (along with the dressing gown and slippers, etc) and checked it into the left luggage department of Adelaide railway station.

Prediction #5: that same morning, he did something simple that accidentally had the effect of making him hard to trace – he shaved off the beard that he had grown in hospital, to try and look as respectable as he could for meeting Jestyn.

Prediction #6: I believe that it wasn’t poison or a pastie that killed him, but whatever he had been suffering from in the hospital (causing his spleen to enlarge etc).