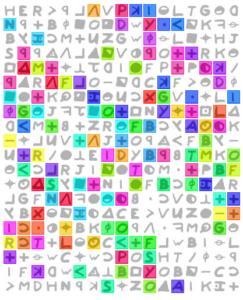

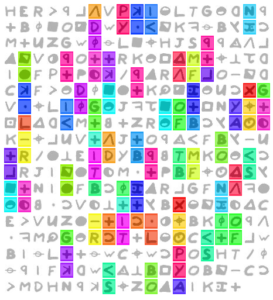

Back in 2014, Voynich blogger Ellie Velinska found what is surely one of the most stunning parallels yet with any of the Voynich Manuscript’s illustrations: a splendidly detailed T-O map surrounded by a wolkenband, placed right at the start (fol. 1r) of BNF Français 565:

This manuscript dates to the start of the 15th century, and was from the library of the famous Jean de Berry (he of “Les Tres Riches Heures” fame), surely one of the greatest art patrons in history.

“Plurima Orbis Imago”

Interestingly, there is some discussion about this specific T-O map in a (very readable) 1990 French article by Arnaud Pascal: “Plurima Orbis Imago. Lectures conventionnelles des cartes au Moyen Age”. In: Médiévales, n°18, 1990. Espaces du Moyen-âge. pp. 33-51;, which also contains a good number of pictures of T-O maps. It reads:

Bien plus, en 1377, le manuscrit parisien du Livre du Ciel et du monde , traduction française du De cœlo d’Aristote par Nicole Oresme inscrit à trois reprises sur la surface d’un globe la forme T-O. Mais celle-ci a été entièrement pervertie, sinon dans sa forme, du moins dans son orientation, et plus encore dans sa signification ; l’une de ces figures, plus détaillée que les autres, nous permet en effet d’en percevoir les détails : l’hémisphère inférieur est entièrement occupé par une série d’ondulations bleues ; le quart supérieur gauche porte des ondulations vertes et bistres ; quant au quart supérieur droit, son fond vert est décoré d’arbres et d’une construction rectangulaire ; le coin supérieur gauche porte un enclos. Nous sommes bien loin ici du schéma tripartite des continents, dont le T a été renversé au profit d’une orientation qui semble être désormais au nord, et il n’est pas difficile de reconnaître dans le quart supérieur droit la terre habitée, et, probablement, le Paradis symbolisé par un enclos, et dans le quart supérieur gauche un autre monde habitable inconnu, soit qu’il soit séparé de la terre habitée, soit qu’il en constitue le prolongement inexploré ; enfin, vers le sud, ne subsiste plus qu’une vaste masse océanique… Si le symbole demeure, son interprétation n’a plus rien de commun avec celle qui soustendait le choix de son image. [p.50]

My (lightly-edited) Google Translate translation follows:

Moreover, in 1377, the Parisian manuscript of the Livre du Ciel et du monde (the French translation of Aristotle’s De cœlo made by Nicole Oresme) inscribed a T-O design on the surface of a globe three times. But here this shape has been totally perverted, if not in its form, then at least in its orientation, and even more so in its meaning; one of these figures [on f1r] is more detailed than the others, and so allows us to perceive all its fine details: the lower hemisphere is entirely filled with a series of blue undulations; the upper left quarter contains green and sooty-brown undulations; the upper right green quarter is decorated with trees and a rectangular building; its upper left corner contains a [walled] enclosure. Here, we are very far from the [traditional] tripartite continental scheme whose T-shape has been rotated in favor of an orientation which now seems to be to the north, and it is not difficult to recognize in the upper right quarter the inhabited earth, and, probably, Paradise symbolized by an enclosure, and in the upper left quarter another unknown habitable world, whether it be separated from the inhabited earth or is its unexplored regions; finally, towards the south, there remains only a vast ocean mass. If this symbol stands correct, its interpretation no longer had anything in common with that which underlies the choice of its image.

The short version is essentially that Arnaud thinks that because this specific T-O map is both rotated relative to the other T-O maps and appears to contain quite different matter in its three divisions, it is “entièrement pervertie”, and so largely stands outside the medieval T-O tradition. If this is correct, then what we are looking at in the Voynich Manuscript’s “Andromeda” T-O page would seem to be a curiously stripped-down copy of a very specific T-O map.

Jean de Berry’s library

This is the point where I’d really like to talk about the complicated dispersal of Jean de Berry’s astronomical library after his death (probably from the plague) in 1416: but I can’t quite achieve this.

The problem is that there is so much written about the sumptuous detail (and complicated painting history) of Les Tres Riches Heures, that a couple of hours on and it still feels like I’m drowning in all the Les Tres Riches Heures details. An entirely typical example of what I’m talking about is Inès Villela-Petit’s Dans le miroir du prince: Jean de Berry et son livre”.

All I’ve actually managed to find is Inventaires de Jean duc de Berry (1401-1416) publiés et annotés par Jules Guiffrey (1894-1896). There, page CLXXIII of Guiffrey’s Introduction mentions it:

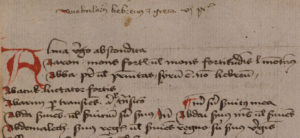

52. Livre de la Sphere par Nicolas Oresme et le livre du ciel et du monde d’Aristote, traduit par le meme (Inv. A, 877 — Bibl.Nat.,ms.fr. 5G5).— In-fol. de 172 feuillets, en ecriture cursive,avec quelques miniatures (auteur offrant son livre a un prince) et figures astronomiques. Au dernier feuillet, inscription du due de Berry dans sa forme hahituelle.

…while the inventory item itself is on fol. 135v, listed as item #877 on p.230 of Guiffrey:

877. Item, un livre en françois, de l’Aristote (2), appelle Du ciel et du monde; convert d’un drap de soye ouvré, doublé d’un viez cendal, à deux fermouers d’argent dorez, esmaillez aux armes de Monseigneur, assis sur tixuz de soye vermeille.

[B, no 1003. — S G, no 469; prisé XII liv. x s. t.]

Can anyone do better and point me at a book or article (in any language) that tries to trace the dispersal of Jean de Berry’s fabulous library? Someone must have at least attempted this, surely?