Following a trail of breadcrumbs from my recent post on Johann Adam Schall von Bell, I’m returning to the issue of whether the VMs could ever have had a Far Eastern origin. To recap, Jacques Guy originally proposed Chinese as a kind of linguistic fou-merde joke on the Voynich research community, only to be unhappily surprised when people started taking it seriously enough to dig up evidence why he might actually have been right. Guy’s “Chinese theory” was, then, somewhat like the Rosicrucian manifestos, in that it was a ludibrium that somehow managed to survive and thrive quite independently of its creator.

Of course, every class of Voynich theory has its naysayers (who normally outnumber the proposer[s] by some 1000:1). In this instance, such people typically point to three major areas of difficulty that any particular Chinese theory would have to overcome – cultural mismatch, codicological mismatch and linguistic mismatch.

Cultural mismatch is the easiest one of the three: where are the Chinese faces, Chinese motifs, Chinese artefacts, Chinese sequences, etc? Search as hard as you like, but you’ll probably (despite what some novelists like to pretend) only find signs of late medieval European culture in there – baths, castles (yes, with swallowtail merlons), European herbals, heads in the roots, cryptoheraldry (eagle, lion, etc)… essentially the same set of cultural conceits that you can see in real Quattrocento herbals and related manuscripts (oh, and in the so-called “alchemical herbals”, which are neither alchemical nor herbal, strictly speaking). I’m also somewhat culturally suspicious about the apparent 30 x 12 = 360-degree division in the zodiac section, because Chinese astronomy before Johann Adam Schall von Bell had long been based on a 365.25 day astronomical year (no matter how awkward this made the maths).

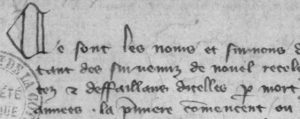

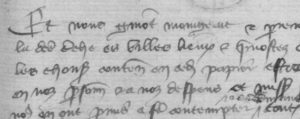

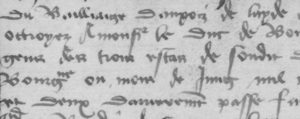

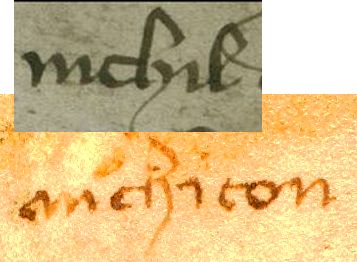

Codicological mismatch is also fairly easy to spot: why would a mysterious Chinese herbal have marginalia and quire numbers written in various 15th century hands? If you are arguing that the VMs is a genuine Far Eastern linguistic artefact (i.e. that it is not openly deceptive), then you’d need to have a particularly strong narrative argument if you are going to try to date its return to Europe much after 1500 (or even 1450). The vellum also seems to have a physically European origin, so this too needs to be taken account of. Furthermore, Voynichese’s general ductus seems to fall within the range of late medieval European styles (it was written by someone fairly adept with a quill rather than with a brush), so the most likely point of codicological departure here would always be that the VMs was written by a European rather than by a Chinese person.

Linguistic mismatch is perhaps both the hardest to spot as well as the hardest to deal with. The core of the Chinese theory was based on Jacques Guy’s amused observation that the frequent “CVCV…” patterns found in Voynichese (such as “otolal“, etc) might be not so much a highly-structured consonant-vowel linguistic artefact as a tonal transcription artefact. That is, that Voynichese is ‘simply’ a structured tonal rendition of an exotic language such as Mandarin Chinese etc, and that perhaps a lot of the letter-following structures we observe are caused by limitations of the way that tones happen to work in that language. OK… but given that the very first tonal rendition of Chinese was apparently attempted by Matteo Ricci in 1583-1588 (the point where the whole idea of a tonal transcription seems to have first appeared), this would seem to point to quite a strong earliest dating for the VMs of (say) 1590 or so, unless you’re going to rewrite a fair bit of the history books etc in your quest to tell your narrative.

Now, you really don’t have to have as big a Renaissance brain as Anthony Grafton’s to be able to notice the contradiction here: which is that for a Chinese theory to overcome the codicological mismatch it seems to require a pre-1500 dating, while for it to overcome the linguistic mismatch it seems to require a post-1590 dating, while simultaneously overcoming the quite separate (and quite large) cultural mismatch issues. The easy answer, of course, is simply to ignore any such problems and just get on with telling your story: it’s far harder to tackle the underlying mismatches and see where they take you.

Incidentally, there’s a little-known interview with Guy Mazars and Christophe Wiart in Actualites en Phytotherapie to be found here (in French) where they propose that many of the Voynich Manuscript’s mysterious plants may in fact be East Asian plants (for example, that f6v depicts Ricinus communis) or Indian plants (they think that many of the plants shown are types of Asteraceae, with f27r representing Centella Asiatica). But you’d have to point out that there are also many, many, many plants in the VMs that are unlikely to match anything these (very learned) experts on Indian and East Asian plants have ever seen. Make of all this what you will (as per normal).