As should be pretty clear from my posts over the years, I’m a big fan of René Zandbergen: he’s one of the very few Voynich researchers that have managed to keep a consistently clear head over the years, and it is his generally even-handed approach that casts a pleasantly affable shadow over voynich.nu, the website he put together many years ago and still one of the few genuinely useful general-purpose Voynich research resources in Internetland. (Please don’t get me started on the uselessness of the Wikipedia page, I want to keep this under 1000 words).

And so in many ways the news that René has now taken back control of voynich.nu (he stopped updating it in 2004, and then handed it over to Dana Scott to look after for a few years) and begun an HTML makeover on it comes as a very pleasant surprise. It’s already looking much better, and no doubt it will carry on improving for a while yet.

I suppose the key question, though, boils down to this: really, what have we learnt about the VMs in the last six years? And how does the whole voynich.nu programme fit in with where we are now?

It’s important to remember that René’s website, for all its substance, is not some kind of “Encyclopaedia Voynichiana“, trying to compile every comment ever made on every feature, drawing, paragraph, line, word, letter. Rather, it concerns itself at least as much with the historiography of the VMs as with the VMs itself. For some people, that is a strength: yet for me, that remains its central weakness. The basic historiographic problem is that the VMs’ provenance shudders to an awkward halt circa 1608, even though it is (demonstrably, I believe) significantly older than this – in fact, if the recent radiocarbon dating is broadly reliable, the VMs probably predates its appearance at the Rudolfine court by more than 150 years. Which is a bit like trying to use Twitter to grasp the dynamics of Queen Victoria’s court.

What, then, should a 2010 voynich.nu look like? In many important ways, we’ve lost all the major archival battles: Marci pointed us to Kircher and Kircher pointed us to Baresch (and that was the end of that), while Rudolph II and WMV jointly got us to Sinapius (and that was the end of that). All of which formed a pleasant historical pear tree to climb, but ultimately one with no fruit, low-hanging or otherwise. We have all the pathology of a history, but none of the substance: for all the patient research fun trawling the archives can be, this approach has not helped us.

And from where I’m sitting, the minute we start defocussing to allow the tsunami of historical possibilities and dead-end theories to wash over us (Wikipedia, anyone?), we’ve basically lost the epistemological fight too. The annoying thing about the VMs is that even though it really is, as I once noted, like a million piece jigsaw, it would probably only take 20 or 30 carefully chosen observations about Voynichese to unlock its cipher. But which 20 or 30 would be the key? We’ll only know in retrospect, I guess. 🙂

Perhaps a revised voynich.nu circa 2010 should focus not on its (let’s face it, fairly damaged and unhelpful) historiography, but rather on what we’ve genuinely learnt about the VMs in and of itself: by which I mean things like…

- the difference between Currier A and Currier B (and all the shades inbetween)

- reconstructing the original page order

- places where the cipher breaks down and/or is hacked (such as space insertion ciphers)

- apparent copying errors

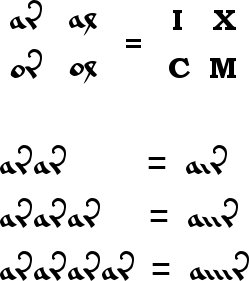

- letter stroke construction and variations

- document constructional details, gatherings vs quires

- marginalia

- internal layering

- the various painters

- handwriting differences and evolution

All of which is very “Voynich 2.0”, but there you go. Really, we do now know a great deal about the VMs that isn’t to do with Marci, Newbold, Brumbaugh, etc: in fact, we have plenty of reasons to be optimistic if we but allow ourselves to be!