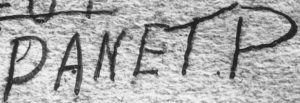

One thing that annoyed me about the Ohio Cipher was that the quality of the newsprint scan of the original 3rd July 1916 article was simply terrible.

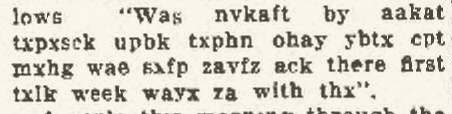

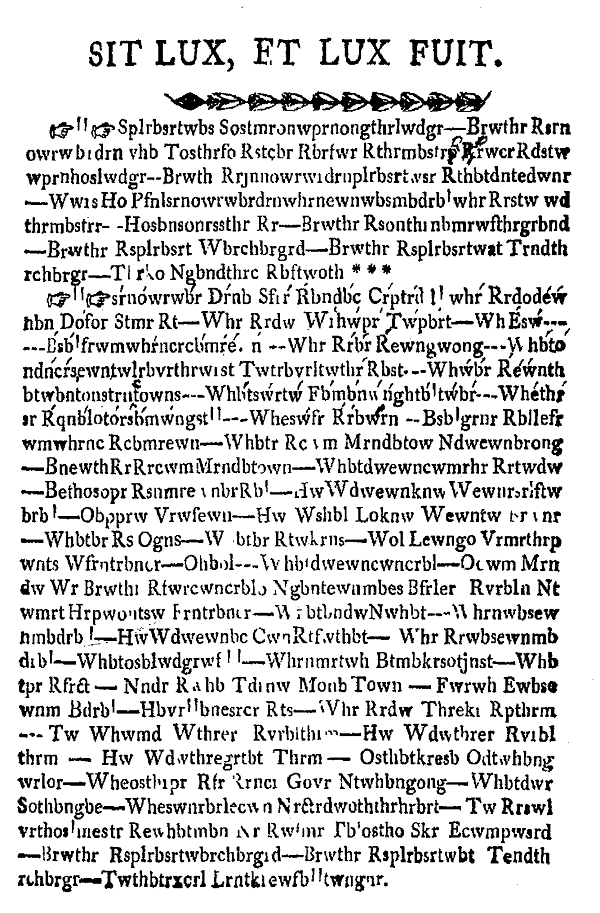

Yes, it really was exactly that bad. Having said that, the version of the same cipher in the follow-up 7th July 1916 article was, comparatively speaking, in excellent shape:

But… which was the correct version of the cryptogram? What’s worse, both of these differed again from the one that ended up in the Futility Closet nearly a century later. So will the real Ohio Cipher now please stand up, please stand up? (…so that we can give it a proper go at solving it, at least partially).

Anyway, a little earlier this year I had a good idea as to how to resolve this: why not find a list of newspaper archives that might possible hold a physical copy of the Lima Times-Democrat from that particular day (3rd July 1916), and see if I could get a fresh scan of it from there? There must, I reasoned, surely be more than a single extant copy of that particular edition, and in all probability they can’t all be as bad as the online one I’d been working with, surely?!?

Hence I contacted the Ohio Historical Society to see if they had a list of such archives, and yesterday got an unexpectedly positive response from this via Tom Rieder of the Ohio History Connection, Columbus OH. He very kindly scanned two different copies of the same article and sent them through to me (they’re at higher resolution than they appear within the blog post body, so feel free to click through to them in all their fuzzy monochromatic glory):-

So, thanks to Tom Rieder’s help, I think we can now say with a reasonable amount of certainty that the Ohio Cipher’s ciphertext was similar but not quite identical to the second version given above, and should read:-

Was nvlvaft by aakat txpxsck upbk txphn ohay ybtx cpt mxhg wae sxfp zavfz ack there first txlk week wayx za with thx

What does this mean? Here we go (at last)… 🙂

If you try to read this off the page as a normal monoalphabetic cipher, the fact that “txp” occurs twice and “tx” occurs four times (and that “TH” is the most common letter-pair in English) would probably make you strongly suspect that “txp” = “THE”. Further you’d probably like to hazard a guess at this point that “txlk” = “THIS” and that “ybtx” = “WITH”. (“aakat” I don’t believe is correct, so let’s skip past that that for the moment.)

But… this approach simply doesn’t work. Even putting only the cipher-like words into CryptoCrack as a patristocrat yields gibberish-like plaintext (such as “fmomewseenesstaturngainstalfpleddistrasktlycebutwahemwhernstoncedthe”, which isn’t particularly close to anything anyone apart from a statistical linguist might describe as a normal language).

There also seems to be some kind of odd-even pattern to the letters, in that ZA appears three times all on even letter boundaries. So my suspicion is that what we’re looking at here is something like a Frankenmixture of plaintext and Polybius ciphertext (but indexed with letters rather than numbers), i.e. with (say) [ A P S U X ] on one side and [ T H K M Z ] across the top, plus other stuff (such as spelling mistakes, transmission errors and possibly extra letters coded as themselves) to confuse the picture. *sigh*

I’m sorry if that’s not as robust a decryption-style reading as you’d like to be getting from Cipher Mysteries, but it is what it is, and please feel entirely free to see if you can do better yourself, ain’t nothin’ stoppin’ ya. 🙂