In the last post, I brought together all the sightings of the October 22 1896 Meteor I could find, and was able to conclude that they were all indeed sightings of an unusual meteor (rather than of a mystery airship). So… what remains? What was the first actual sighting of the 1896 California Airship Flap?

Daniel Cohen’s extra sightings

Cohen adds some early extra sightings that weren’t in Loren E. Gross’ book, that I thought need checking out. For example, Cohen reports (p.9) that “in the last week of October [1896], C. T. Musson, a fruit rancher from Placer County, California, also reported three lights in the sky. He estimated that they were moving at about 100 miles an hour, and were the “prettiest sight” he had ever seen.“

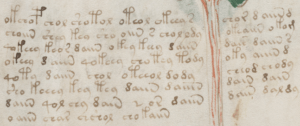

After a few searches, I found the original story in the San Francisco Call of 25 November 1896 p.2:

Sighted Triple Lights

A Rapid Aerial Traveler Observed in Placer County

BOWMAN, Placer County, Cal., Nov. 24 – The articles published in THE CALL and other papers in reference to the observed mystical aerial traveler have aroused great interest here. Several persons in this locality have been favored with a view of the strange visitor.

C. T. Musso, a fruit rancher, and several members of his family affirm that about four weeks ago and shortly after dark they saw a singular sight, which they are now convinced could have been nothing else than the much-discussed airship. Mr. Musso says he saw the “prettiest sight that his eyes ever viewed.” It appeared to be three very bright lights moving horizontally and easterly at a rate of perhaps 100 miles an hour.

A. H. Thompson, a painter, states that about the same time he saw a similar sight, which he describes as being three very bright and large lights appearing about eight feet apart, and the forward one as being larger and brighter then the rest, and moving horizontally eastward rapidly and gracefully.

Professor S. D. Musso states that about two weeks ago he and his wife saw a similar sight moving in the same direction and with about the same velocity. He feels quite confident that it was not a meteor, as there were three lights appearing about seven feet from each other in a direct line, the forward one being larger than the other two. The light, he states, was different from meteoric light, the velocity was too slow for a meteor, and it was traveling horizontally as long as was seen, which was for several minutes.

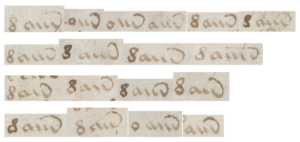

Cohen also briefly mentions (p.9) a sighting from around this earlier time by “a young San Francisco woman named Hegstrom”. Again, I eventually found the original report in the Record-Union of 23 November 1896, p.4:

Miss Hagstrom, who resides on Telegraph avenue, saw the same object about six weeks ago. The feature that impressed her most was the bright light which she distinctly saw. On returning home she told her brother of what she had seen, but nothing more was thought of it until she read recently that a similar object had been seen in another part of the state.

So, replacing Musson/Hegstrom with Musso/Hagstrom, I feel reasonably confident that both were in fact sightings of the October 22 meteor, rather than first sightings of the mystery airship. I’m also reasonably sure that Cohen was relying on a type-written (and probably somewhat faded) list of sightings.

“A Hunter named Jordan”

Our final pre-Sacramento sighting appears in Cohen (p.9): “One of the most astonishing tales was attributed to a hunter named Jordan, who said that he and some friends had tracked a wounded deer to a remote part of Tamalp[a]is Mountain northwest of San Francisco. There in a clearing he came upon a hidden workshop, and in it were six men working over a strange-looking vehicle.“

Gross’ book on Charles Fort tells this same story (but without giving a source) (p.7): “For example, a hunter claimed he had come across the airship and its inventors while walking through the woods in Marin County. The inventors were quite ordinary people he asserted.“

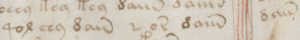

Once again, diligent searching revealed the full story as recounted in a letter published in The San Francisco Call, 23 Nov 1896, p.2, right at the zenith of Californian mystery airship mania:

OTHERS WHO SAW IT

Stories that Corroborate the Fact of the Invention

The following letter from San Rafael explains a phase of the story that has not yet come to light:

SAN RAFAEL, Nov. 22, 1896

Editor Call: The mysterious light mentioned in your valuable paper this morning as seen by several citizens in different parts of the State, and which seems to mystify yourself as well as your readers, is nothing more than an airship, and of this fact I am perfectly cognizant. I think now that I am released of my obligation of secrecy, which I have kept for nearly three months, as the experiment in aerial navigation is a fixed fact and the public or a few of the public at least have seen its workings in the air.

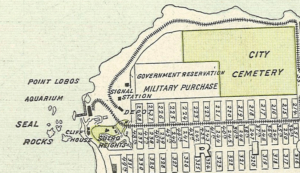

In the latter part of last August I was hunting in the Tamalpais range of mountains, between the high peak and Bolinas Bay. I wounded a deer, and in chasing it I ran onto a circular brushpile about ten feet in height in a part of the mountain seldom visited even by hunters.

I was somewhat astonished, and my curiosity prompted me to approach it, when I encountered a man who sang out: “What are you doing here and what do you want?” I replied that “I had wounded a deer and was chasing it.” He said “that they had been camping here for a month or so and had not seen a deer, but if you think your deer is in the neighborhood I will assist you in finding it as we need a little meat in camp.” This man went with me and in less than 500 yards found my deer. We carried it into the brush corral. And what a sight – a perfect machine shop and an almost completed ship. I was sworn to secrecy and have kept it till this moment. Six men were at work on the “aerial ship.” It is this ship that a few people have seen at night on its trial trip. It returns to its home before daylight and will continue to do so until perfected. Yours, WILLIAM JORDON.”

Once again, even though Cohen’s account has a coupling of niggling typos (Jordan/Tamalpis for Jordon/Tamalpais), it does basically seem to have been well-sourced.

As an aside: according to Familysearch and MyHeritage, there are plenty of “William Jordon”s in California, but my guess is that the right one would prove to be closely related to William Charles Jordon (born 1817), who was registered to vote in San Rafael in 1872 [myheritage], and (I guess) who Familysearch thinks married Mary J. Devine in Sonoma on 15 July 1865.

Mountain Man named Brown

Our final sighting appears in Cohen (p.9), and mercifully doesn’t involve three bright lights in the sky. He writes: “A reclusive mountain man named Brown said he actually observed some sort of vehicle rising from the trees on a mountain ridge near San Francisco. He could not see the thing clearly because of the mountain mist, but he was sure it was quite unlike anything he had ever seen before.“

Well… I’ve searched newspapers.com (and elsewhere) for this without any luck at all (and it doesn’t seem to appear in any of Loren E. Gross’ books). I think there’s a high chance this story did appear in a newspaper around that time, but perhaps a spelling mistake crept in. All the same, this certainly seems to at least be consistent with William Jordon’s story.

Still, three out of four’s not a bad hit rate, and perhaps I’ll find the fourth at some point in the future.