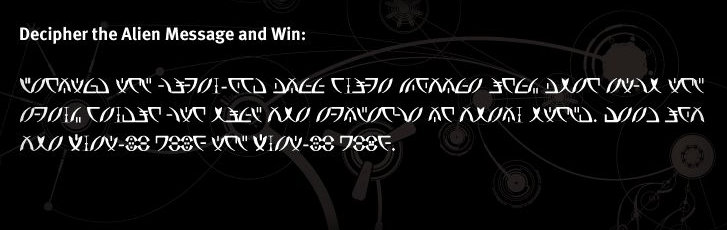

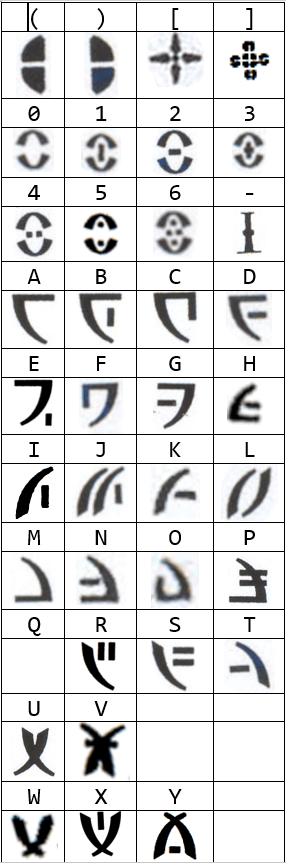

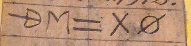

When “Isaac” posted his alien alphabet / antigravity stuff in June 2007, it was (he claimed) in response to recent reports of strange ‘dragonfly’-shaped drones, some of which had the same ‘alien’ writing on them:

- 10 May 2007, Bakersfield, California – “Chad” (April 2007 + 06 May 2007)

- 12 May 2007, Lake Tahoe, Nevada – “Deborah McKinley” (05 May 2007)

- 20 May 2007, Capitola, California – “Raj / Rajman / Rajinder Satyanarayana” (16 May 2007)

- 06 Jun 2007, Big Basin, California – “Stephen” (05 Jun 2007)

- 11 Jun 2007, Big Basin, California – “Ty Branigan” (05 Jun 2007)

Those sightings are well documented in a “One Year Later” article in MUFON Ufo Journal April 2008 (pp. 3-11): the TL;DR version of that is simply that none of the claimed witnesses is credible, sorry. [If you don’t know about MUFON, it describes itself as an independent follow-on to Project Blue Book, and that it always starts by assessing the credibility of witnesses.]

Regardless, I decided (as I did with Isaac’s JPEGs) to take a digital forensic look at the various drone images, to see if there was anything interesting there: and I began with “Chad”.

Chad’s drone images

Chad’s drone story first appeared on Coast to Coast AM, and starts as follows:

Last month (April 2007), my wife and I were on a walk when we noticed a very large, very strange “craft” in the sky. My wife took a picture with her cell phone camera (second photo). A few days later a friend (and neighbor) lent me his camera and came with me to take photos of this “craft”. We found it and took a number of very clear photos. Picture #1 is taken from right below this thing and I must give my friend credit as I was not brave enough to get close enough to take this picture myself!

I started by downloading numerous variations of Chad’s images, but (viewed through a JPEGsnoop microscope) none of them seemed to me to be an original image. However, once I found Chad’s images from the Coast to Coast AM website itself, JPEGsnoop had an absolute field day.

The first image I looked at in depth was “Craft050607b.jpg”:

There’s an absolute riot of EXIF metadata going on here. For a start, we can see that the image creator used Adobe Photoshop Elements, which is sold as a cut-down version of Adobe Photoshop:

[Software ] = "Adobe Photoshop Elements 2.0"

[DateTime ] = "2007:05:06 17:20:08"We can also see that it was saved out in Adobe Photoshop with quality setting 5:

8BIM: [0x0406] Name="" Len=[0x0007] DefinedName="JPEG quality"

Photoshop Save As Quality = 5

Photoshop Save Format = "Standard"

Photoshop Save Progressive Scans = "3 Scans"Similarly, the creator used Adobe Digital Negative (DNG) Converter, which is typically used to import raw (unprocessed) photo data from (generally high-end) digital cameras:

SW :[Adobe DNG Converter ] [ ]

SW :[Adobe Photoshop ] [Save As 05 ] Oddly, though, there was a slice name that seems to imply that this was from a scanned image:

Name of group of slices = "ScannedImage-2"

Number of slices = 1 UUIDs and Melissa

Finally: also embedded in many of the file metadata is a version 1 format UUID. Historically amusingly, its strategy for constructing a universally unique id is by combining a device’s six-byte MAC address with the number of 100-nanosecond ‘ticks’ since midnight 15 October 1582 UTC, which was (as I’m sure you’ll all recall) the precise date when the Gregorian calendar was first adopted.

Decoding Chad’s UUIDs using an online UUID Decoder gives us:

- “Craft050607a.jpg” has UUID 013dfdd9-fc30-11db-b305-b8a28f50b702

- MAC address b8:a2:8f:50:b7:02, generated on 2007-05-07 00:15:04.703125.7 UTC

- “Craft050607b.jpg” has UUID 013dfdd9-fc30-11db-b305-b8a28f50b702

- MAC address b8:a2:8f:50:b7:02, generated on 2007-05-07 00:15:04.703125.9 UTC

- “Craft050607c.jpg” has UUID c822a9ca-fc30-11db-b305-b8a28f50b702

- MAC address b8:a2:8f:50:b7:02, generated on 2007-05-07 00:20:38.390625.0 UTC.

- “Craft050607e.jpg” has no embedded UUID

- “Craft050607x1.jpg” has UUID 8e3de69f-fd14-11db-a9e5-8988b4fa457e

- MAC address 89:88:b4:fa:45:7e, generated on 2007-05-08 03:31:06.515625.5 UTC

- “Craft050607x2.jpg” has UUID 8e3de6a2-fd14-11db-a9e5-8988b4fa457e

- MAC address 89:88:b4:fa:45:7e, generated on 2007-05-08 03:31:06.515625.8 UTC

- This didn’t seem to use Adobe DNG).

- “Craft050607x5.jpg” has UUID 74fb1a10-fd17-11db-a9e5-8988b4fa457e

- MAC address 89:88:b4:fa:45:7e, generated on 2007-05-08 03:51:52.625000.0 UTC

- This too didn’t seem to use Adobe DNG.

At first glance, it might seem we have identified Chad’s two PCs! Except… we haven’t: the OUIs (the top three bytes) of the two MAC addresses are not recognised, so it is almost certain that Adobe’s software picked a random MAC address at the start of each of the two sessions. This is almost certainly because of privacy concerns: what famously happened in 1999 was that the creator of the Melissa computer virus was tracked down via his MAC address embedded in a UUID embedded inside his virus. And so people started randomising the MAC address portion of UUIDs, which eventually led to UUID format v4 and v5.

Hence: unless “Chad” happened to write out any other JPEGs during those two specific sessions, I think we are unlikely to be able to use the MAC address portion of Adobe UUIDs generated in 2007 (and afterwards) to track down anything else linked to this person, alas.

Finally: note that each of these JPEG files contains two UUIDs formed from timestamps that differ by:

- Craft050607a – 200 nsec

- Craft050607b – 900 nsec

- Craft050607c – 333 msec

- Craft050607x1 – 200 nsec

- Craft050607x2 – 200 nsec

- Craft050607x5 – 2.95 sec – this seems to be because the base UUID is that of Craft050607x2 (it was apparently cropped from that image and saved three seconds later)

I don’t really know what this means, but I thought I’d include it anyway.

Lake Tahoe images

I also found copies of the Lake Tahoe images on a (very helpful) Avalon Library page. The two files were called “7013_submitter_file1__070505_02.jpg” and “7013_submitter_file2__070505_03.jpg” (which I presume are partly MUFON case file references).

7013_submitter_file1__070505_02.jpg included some interesting metadata. Overall, JPEGsnoop’s assessment was this:

SW :[Apple ImageIO.framework ] [075 (High) ]

The sensor was annotated as “MSM6500” (which I presume is the Qualcomm chip), and there’s Adobe Photoshop XMP metadata in there too. For once, the EXIF data is consistent with a digital camera:

[ExposureTime ] = 1/21 s

[ExifVersion ] = 02.20

[DateTimeOriginal ] = "2007:05:05 18:52:11"

[DateTimeDigitized ] = "2007:05:05 18:52:11"

[ComponentsConfiguration ] = [Y Cb Cr .]

[Flash ] = Flash did not fire

[FlashPixVersion ] = 01.00

[ColorSpace ] = sRGB

[ExifImageWidth ] = 0x[00000200] / 512

[ExifImageHeight ] = 0x[00000180] / 384

[CustomRendered ] = Normal process

[ExposureMode ] = Auto exposure

[WhiteBalance ] = Auto white balance

[DigitalZoomRatio ] = 2/1

[SceneCaptureType ] = Standard

[SubjectDistanceRange ] = 0The second image was captured five seconds later (also without flash):

[DateTimeOriginal ] = "2007:05:05 18:52:16"Stephen images

Here, the EXIF data (in “IMG_1060”) is definitive about the camera used (the Rebel XT is a good camera, I have one myself):

[Make ] = "Canon"

[Model ] = "Canon EOS DIGITAL REBEL XT"The other camera EXIF data is very much what you’d expect for a daytime shot:

[ExposureTime ] = 1/4000 s

[FNumber ] = F5.6

[ExposureProgram ] = Aperture priority

[ISOSpeedRatings ] = 1600

[ExifVersion ] = 02.21

[DateTimeOriginal ] = "2007:06:05 13:12:49"

[DateTimeDigitized ] = "2007:06:05 13:12:49"

[ComponentsConfiguration ] = [Y Cb Cr .]

[ShutterSpeedValue ] = 7694/643

[ApertureValue ] = 7163/1441

[ExposureBiasValue ] = 0.00 eV

[MeteringMode ] = Pattern

[Flash ] = Flash did not fire

[FocalLength ] = 50 mm

[FlashPixVersion ] = 01.00

[ColorSpace ] = sRGB

[ExifImageWidth ] = 0x[000009C0] / 2496

[ExifImageHeight ] = 0x[00000680] / 1664

[ExposureMode ] = Auto exposure

[WhiteBalance ] = Auto white balance

[SceneCaptureType ] = StandardThis too had an Adobe XAP block, but without any UUIDs.

IMG_1061 was taken two seconds later (properly focusing on the distance):

[DateTime ] = "2007:06:05 13:12:51"IMG_1062 was taken four seconds later again:

[DateTime ] = "2007:06:05 13:12:55"The Ty photos

Interestingly (and this wasn’t lost on forum commenters at the time), these photos were handled by Adobe Photoshop CS2 (“Creative Suite” version 2) Macintosh, as is abundantly clear from the metadata. These annotate an image being loaded (at 22:32:53 on 2007-06-16), modified, and then saved out 5.5 minutes later (at 22:38:20). The time zone was -06:00.

| <xap:CreatorTool>Adobe Photoshop CS2 Macintosh</xap:CreatorTool>

| <xap:CreateDate>2007-06-16T22:32:53-06:00</xap:CreateDate>

| <xap:ModifyDate>2007-06-16T22:38:20-06:00</xap:ModifyDate>

| <xap:MetadataDate>2007-06-16T22:38:20-06:00</xap:MetadataDate>The first image I looked at (DroneBigBasinTy060507aa.jpg) had a UUID of 22702A38-1DB6-11DC-8078-C1028E507E7C, which decodes to:

- Date/time = 2007-06-18 16:08:21.330181.6 UTC

- MAC address = c1:02:8e:50:7e:7c (which, once again, is almost certainly randomised per session)

i.e. 2 days after the CS2 date. JPEGsnoop’s overall verdict:

EXIF Software: OK [Adobe Photoshop CS2 Macintosh]

SW :[Adobe DNG Converter ] [ ]

SW :[Adobe Photoshop ] [Save As 05 ] 60507bb.jpg had XMP but no UUID:

| <xmp:CreateDate>2007-06-16T22:45:28</xmp:CreateDate>

| <xmp:CreatorTool>Adobe Photoshop CS2 Macintosh</xmp:CreatorTool>

| <xmp:ModifyDate>2007-06-16T22:47:47</xmp:ModifyDate>60507cc.jpg had both:

| <xap:CreateDate>2007-06-16T22:50:49-06:00</xap:CreateDate>

| <xap:ModifyDate>2007-06-16T22:52:33-06:00</xap:ModifyDate>

| <xap:MetadataDate>2007-06-16T22:52:33-06:00</xap:MetadataDate>- 5BADA44A-1DEE-11DC-8078-C1028E507E7C

- Date/time = 2007-06-18 22:50:49.180065.0 UTC

- MAC Address = c1:02:8e:50:7e:7c

60507ee.jpg had only XMP:

| <xmp:CreateDate>2007-06-16T22:41:33</xmp:CreateDate>

| <xmp:CreatorTool>Adobe Photoshop CS2 Macintosh</xmp:CreatorTool>

| <xmp:ModifyDate>2007-06-16T22:43:14</xmp:ModifyDate>

60507ff.jpg had only XMP: | <xmp:CreateDate>2007-06-16T22:53:02</xmp:CreateDate>

| <xmp:CreatorTool>Adobe Photoshop CS2 Macintosh</xmp:CreatorTool>

| <xmp:ModifyDate>2007-06-16T22:54:34</xmp:ModifyDate>

60507gg.jpg had only XMP

| <xmp:CreateDate>2007-06-16T22:38:36</xmp:CreateDate>

| <xmp:CreatorTool>Adobe Photoshop CS2 Macintosh</xmp:CreatorTool>

| <xmp:ModifyDate>2007-06-16T22:40:57</xmp:ModifyDate>

60507hh.jpg had only XMP:

| <xmp:CreateDate>2007-06-16T22:43:29</xmp:CreateDate>

| <xmp:CreatorTool>Adobe Photoshop CS2 Macintosh</xmp:CreatorTool>

| <xmp:ModifyDate>2007-06-16T22:44:44</xmp:ModifyDate>60507ii.jpg had only XMP:

| <xmp:CreateDate>2007-06-16T23:03:21</xmp:CreateDate>

| <xmp:CreatorTool>Adobe Photoshop CS2 Macintosh</xmp:CreatorTool>

| <xmp:ModifyDate>2007-06-16T23:05:26</xmp:ModifyDate>60507jj.jpg had both:

| <xap:CreateDate>2007-06-16T23:01:06-06:00</xap:CreateDate>

| <xap:ModifyDate>2007-06-16T23:03-06:00</xap:ModifyDate>

| <xap:MetadataDate>2007-06-16T23:03-06:00</xap:MetadataDate>- UUID 668A3FCB-1DEF-11DC-8078-C1028E507E7C

- Date/time = 2007-06-18 22:58:16.899783.5 UTC

- MAC address = c1:02:8e:50:7e:7c

60507kk.jpg had both:

| <xap:CreateDate>2007-06-16T22:58:42-06:00</xap:CreateDate>

| <xap:ModifyDate>2007-06-16T23:00:30-06:00</xap:ModifyDate>

| <xap:MetadataDate>2007-06-16T23:00:30-06:00</xap:MetadataDate>- UUID = 668A3FC7-1DEF-11DC-8078-C1028E507E7C

- Date/time = 2007-06-18 22:58:16.899783.1 UTC

- MAC address = c1:02:8e:50:7e:7c

Finally, 60507ll.jpg had both:

| <xap:CreateDate>2007-06-16T22:55:22-06:00</xap:CreateDate>

| <xap:ModifyDate>2007-06-16T22:58:17-06:00</xap:ModifyDate>

| <xap:MetadataDate>2007-06-16T22:58:17-06:00</xap:MetadataDate>- UUID = 5BADA452-1DEE-11DC-8078-C1028E507E7C

- Date/time = 2007-06-18 22:50:49.180065.8 UTC

- MAC Address = c1:02:8e:50:7e:7c

From this, it seems as though these images were initially processed on 2007-06-16 between 22:32 and 23:03, before being saved out two days later (as a batch?) between around 22:50 and 22:58.

The Drone Research Team Forum

According to MUFON, Raj’s 12 drone pictures were sent to Linda Moulton Howe who scanned them in and posted them. So any digital forensic analysis of these should only lead back to her, not to him.

In terms of content analysis, I should note that one group of 2007-drone researchers (the now-defunct Drone Research Team, though their pages live on in the Wayback Machine) believed that they had identified the precise telegraph pole in Capitola, CA that appeared in Raj’s pictures. They even printed out 400 flyers and posted them to all the pole’s neighbours to see if anybody had seen anything. (I believe the answer was a resounding no.)

Incidentally, the Drone Research Team’s main members were (according to this site):

- Tomi01uk (UK)

- Onthefence (Canada)

- 10538 (USA)

- Nemo492 (France)

- Raska (France)

- Elevenaugust (France)

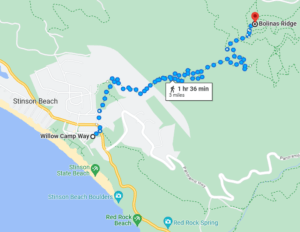

To identify the site, they hired private investigators Frankie Dixon and T.K. Davis, but also asked them to try to identify the other drone sites. (A story covering their search ended up in the Los Angeles Times in 2008.) Here’s an animation created by arkhangels overlaying one 2007 drone image with an image taken by the private investigators:

Even though “Chad” claimed to have taken his photos in Bakersfield, it turned out that the actual location was a little distance away. Similarly, the “Stephen” drone picture turned out to be not Big Basin State Park, but (thanks to Pacific Gas and Electric meter reader Tom) Bohlman Road Ridge in Saratoga.