By now, everyone and his/her crypto-dog must surely know that the second Beale Cipher (“B2”) was enciphered using a lookup table created from the first letters of the words of the Declaration of Independence: that is, a number N in the B2 ciphertext corresponds to the first letter of the Nth word in the DoI.

Even working out that this was the case was far from trivial, because the version of the DoI used was non-standard, and there were also annoying numerical shifts (which strongly suggest that the encipherer’s word numbering messed up along the way). There were also a few places where the numbers in the B2 ciphertext appear to have been miscopied or misprinted.

Yet I don’t share the view put forward by some researchers that this would have made it nigh-on-impossible for anyone to figure out that the DoI had been used, simply because most of the number instances are low numbers, i.e. they are concentrated near the front end of the DoI where there are fewer differences with normal DoI’s, and before the numbering slips started to creep in. This means that even if you used nearly the right DoI, a very large part of the ciphertext would become readable: and from there a persistent investigator should be able to reconstruct what happened with the (not-so-straightforward) high-numbered indices to eventually fill in the rest of the gaps. Which is basically where Beale research had reached by the time Ward’s pamphlet was printed.

So far, so “National Treasure”. But this isn’t quite the whole story, because…

B1 Used The Same Table!

Even if we have so far failed to work out precisely how B1 was enciphered, we do also know something rather surprising, courtesy of Carl Hammer and Jim Gillogly: that the process used to construct B1 used almost exactly the same DoI used to encipher B2. Jim Gillogly, in his famous article “The Beale Cipher: A Dissenting Opinion” [April 1980, Cryptologia, Volume 4, Number 2, pp.116-119, a copy of which can be found in the Wayback Machine here] concluded that the ‘plaintext’ patterns that emerged from this were artificial nonsense, and so B1 (and by implication B3) were empty hoax texts, i.e. designed to infuriate rather than to communicate.

From the same evidence, Carl Hammer concluded (quite differently) that B1 and B2 were encrypted in the same way using the same tables, though he didn’t have a good explanation for the mysterious patterns. For what it’s worth, my own conclusion is that B1 and B2 were encrypted slightly differently but using the same tables, which is kind of a halfway house between Gillogly’s coglie and Hammer’s clamour. 😉

All three agree on this: that if you plug the DoI’s first letters into the B1 ciphertext, mysterious patterns do appear (more on those shortly). But for many years, my view has been that Gillogly’s end conclusion, though clear-headed and sincere, was both premature (because I don’t believe he had eliminated all possible explanations) and unhelpful (because it had the possibly unintentional effect of stifling nearly all subsequent cryptological research into the Beale ciphers).

Regardless, it seems highly likely that almost exactly the same DoI was used to construct B1 as was used to encipher B2. This is because the statistically improbable mysterious patterns only emerge in the B1 plaintext if you use the DoI.

Furthermore, what I think is quite striking is, as I pointed out some years ago, that if you use the corrected cipher table (i.e. the cipher table generated from the same DoI and using the same numerical mistakes as were used in the cipher table used to construct the B2 cipher text), the mysterious patterns not only remain, but become even more statistically improbable than before.

What this implies, I believe, is that not only was the same non-standard DoI used in both, but also the same enciphering tables derived from it, numerical errors and all.

Here’s what B1 looks like when combined with the raw DoI (numbers above 1000 map to ‘?’)

s c s ? e t f a ? g c d o t t u c w o t w t a a i w d b i i d t t ? w t t a a b b p l a a a b w c t

l t f i f l k i l p e a a b p w c h o t o a p p p m o r a l a n h a a b b c c a c d d e a o s d s f

h n t f t a t p o c a c b c d d l b e r i f e b t h i f o e h u u b t t t t t i h p a o a a s a t a

a t t o m t a p o a a a r o m p j d r a ? ? t s b c o b d a a a c p n r b a b f d e f g h i i j k l

m m n o h p p a w t a c m o b l s o e s s o a v i s p f t a o t b t f t h f o a o g h w t e n a l c

a a s a a t t a r d s l t a w g f e s a u w a o l t t a h h t t a s o t t e a f a a s c s t a i f r

c a b t o t l h h d t n h w t s t e a i e o a a s t w t t s o i t s s t a a o p i w c p c w s o t t

i o i e s i t t d a t t p i u f s f r f a b p t c c o a i t n a t t o s t s t f ? ? a t d a t w t a

t t o c w t o m p a t s o t e c a t t o t b s o g c w c d r o l i t i b h p w a a e ? b t s t a f a

e w c a ? c b o w l t p o a c t e w t a f o a i t h t t t t o s h r i s t e o o e c u s c ? r a i h

r l w s t r a s n i t p c b f a e f t t

Of the many artificial-looking sequences here, the one that caught Hammer’s and Gillogly’s eyes was:

a b f d e f g h i i j k l m m n o h p p

If we instead plug the same set of B1 numbers into the corrected DoI cipher table, this is what you get:

s b s ? e t f a ? g c d o t t u c w o t w t a a i s d b t i d t t ? w t f b a a b a d a a a b b c d

e f f i f l k i g p e a m n p w c h o c o a l l p m o t a m a n h a b b b c c c c d d e a o s d s t

b n t f t a t p o c a c b c d d e p e t p f a b t h i f f e h u u b t j t t t i h p a o a o s a t a

b t t ? m n m p a a a a r b o p j d t f ? ? t s b c o h d a f a c p n r b a b c d e f g h i i j k l

m m n o h p p a w t a o m b b l s o e s a t o f i s p c t a o l b t f l h d o a h g b w t e n c l c

a s s a a s t a t d t g t a w g f e a a o c a a a t t w h t t t a a o e t s a f a a s b s t c i h r

c a b t o t s c t d c n h w t s t e h i o o a t s t w t t s o f a a s t a a m s i w c p c w s o t l

i n i e e i t t d a t t p i u f a e r f a b p t c t a o i d n a t t o a t s t a ? ? a t m a t w n w

t t o c w t o t p a t s o t e b a t r c h b t o g a w c d r o l i t i a h l w a a s ? b c s t a f a

e w c m ? f t o w l t s o c c t e w t a f o a o w t t t t t o t h r i s u e o h a c u a f ? p o i h

r m s s t r a s n i t p c t u o w f t t

This yields even more mysteriously ordered patterns than before:

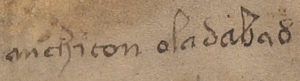

* a a b a d a a a b b c d e f f i f

* a b b b c c c c d d e

* a b c d e f g h i i j k l m m n o h p p

Sorry, Jim, but something is going on there to cause feeding B1’s numbers into the refined DoI to produce these patterns: and even if I agree that the rest of the Beale pamphlet is a steaming heap of make-believe Boy’s Own backfill, I still don’t think the B1 ciphertext is a hoax. There’s just too much order.

Filling In The Gaps

Now, if it is true that exactly the same cipher table was used to construct both B1 and B2 (and though I believe this is highly likely, I have to point out that this remains speculative), these mysterious patterns may offer us the ability to advance our understanding of the cipher table yet further. This is because we can look at those places where the mysterious patterns break down in mid-sequence, and use those places to suggest corrections either to the table or to the B1 ciphertext itself. That is, even if we can neither decrypt nor understand B1, we can still use its mysterious plaintext patterns to refine our reconstruction of the enciphering table used to construct it and/or our understanding of the B1 ciphertext itself.

150=a 251=a 284=a 308=b 231=b 124=c 211=d 486=e 225=f 401=f 370=i 11=f

370=importance BUT 360=forbidden, so I suspect that 370 may have been a copying slip for 360.

24=a 283=c 134=b 92=c 63=d 246=d 486=e

283=colonies BUT 284=and, so I suspect that 283 may have been a copying slip for 284.

890=a 346=a 36=a 150=a 59=r 568=b

59=requires, but I’m not sure what happened here.

147=a 436=b 195=c 320=d 37=e 122=f 113=g 6=h 140=i 8=i 120=j 305=k 42=l 58=m 461=m 44=n 106=o 301=h 13=p 408=p

301=history BUT 302=of, so I suspect that 301 may have been a copying slip for 302.

OK, I’d agree this isn’t a huge step forward: but given that the printed version of (the solved!) B2 has seven similar copying slips…

* B2 index #223 is ’84’, but should be ’85’

* B2 index #531 is ’53’, but should be ’54’

* B2 index #571 is ‘108’, but should be ‘10,8’

* B2 index #590 [#591] is ‘188’, but should be ‘138’

* B2 index #666 [#667] is ‘440’, but should be ’40’

* B2 index #701 [#702] is ’84’, but should be ’85’

* B2 index #722 [#723] is ’96’, but should be ’95’

…I’d expect that we’re likely to have between 10 and 20 copying slips in B1’s series of numbers. That, combined with the larger ratio of homophones (i.e. as compared with the size of the ciphertext), keeps pushing B1 out of the range of automated homophonic ciphertext solvers. So all we can do to try to correct for those may well be a help!