It’s one of those strange stories that sounds oddly romantic at first, then somewhat confusing, before ultimately ending up sad. The tale of Nora Emily (‘Netta’) Fornario’s curious death on Iona in November 1929 was recently picked up by Mental Floss (which is where I first heard of it), and if you just want to read a fluffy mystery version of how an occultist came to die an unexplained death on a Scottish Island, that’s probably where your reading should begin and end.

But who was she? What happened to her? And what were the curious papers she had that police found, but which have since disappeared? Sorry, but rather than accepting magickal claims that she was killed by some kind of psychic attack (as Dion Fortune implied in 1930), I’d rather be completely boring and look at the facts.

Who Was She?

Curiously, though there are countless websites to be found regurgitating facts (and fact-like things), I found only one solidly reliable source: Dedemia Harding of The New Society of the Golden Dawn in Bradford. Dedemia’s short – and I mean extremely short – booklet called “The Netta Fornario Experience“, which is only available as a Kobo ereader ebook (£0.99), lays out the bare bones of Fornario’s life:

* She was born in Cairo, Egypt in 1897, the daughter of Norah Edith Ling and Guiseppe Nicola Raimundo Fornario, an Italian doctor.

* After her mother died in 1898, she was placed in the care of well-to-do tea dealer Thomas Pratt Ling, her maternal grandfather.

* She lived with him and his family at Leigham Holme, Leigham Court Road, Streatham

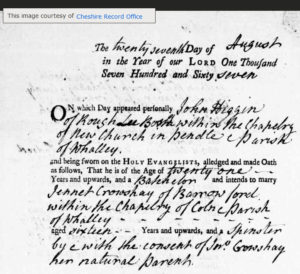

* Upon Thomas Pratt Ling’s death in 1909, his will (which was also reported here, here and no doubt in many other places) left money to his granddaughter Netta but with stringent conditions:

The will has been proved of Mr. Thomas Pratt Ling, of Bracondale, Dorking, Surrey, aged seventy-four, tea merchant, who died in February. He left £12,000 upon trust for his granddaughter, Marie Nora Emily Edith Fornario, “Provided that she shall remain under the guardianship of his son George or other person approved by his trustees and shall not for- sake the English Protestant Faith, or marry a person not of that Faith, or marry a first cousin on either her father’s or her mother’, side, under penalty of losing one-half of he; interest in this sum, and he also providel that the income should be paid to her in the United Kingdom, unless for a cause to be certified by medical certificate, or other cause to be approved by his trustees, she shall not be in the United Kingdom.”

* In 1911, she was (according to this site) at the Ladies’ College boarding school, 2 Grassington Road, Eastbourne.

* In 1921, according to Gareth Knight in a 2006 talk at the Canonbury Masonic Research Centre, Netta was appointed Outer Guardian of a co-masonic lodge in Sinclair Road in Hammersmith.

* On 4th July 1922, her naturalization certificate A9304 was issued, as per document HO 144/1765/431695 at the National Archives. Here, her name was listed as Marie Norah Emily Edith Fornario.

For her writings, this Strange History blogpost is pretty good. It lists:

* (1917) “Four sea idylls” written by M. Fornario, in “Memories of the Deep” by Gertrude Bracey, London: Boosey & Co

* a review of The Immortal Hour (an occult opera about fairies) under the name ‘Mac Tyler’, which she claimed to have watched “some three and twenty” times. (Full review here.)

* (1928) “The Use of Imagination in Art, Science and Business”, in The Occult Review

Death on Iona

As so often happens, there are a number of different accounts of her mysterious death on the Scottish island of Iona. What seems closest to the truth is the 1955 account by Alasdair Alpin MacGregor: this relied “on the testimony of two Ionan-dwelling friends Lucy Bruce and Iona Cammell”, the latter of whom wrote a (now-lost?) obituary for Netta in The Atlantis Quarterly. I believe (though I’m not sure) that MacGregor’s account appeared in his (1955) “The Ghost Book: Strange Hauntings in Britain”, Robert Hale, London: it was largely reproduced on this Strange History page.

Anyway, according to MacGregor: late one evening, Fornario left the place she was staying in on Iona (to which she had been attracted by its connections with fairies and magic) but then failed to return.

The customary knock on her door the following morning brought no response. She had gone! Whither, no one knew. Neatly arranged in the room were her clothes and jewellery. As the hours wore on, and she did not return, everybody became alarmed for her safety. Soon the islanders were searching the bays and inlets for her, searching the rocks and moorlands – searching for her on what remained of the short, dark northern November day. They failed to find her. The ensuing night was moonlit, calm and frosty. With the coming of dawn, the searchers were out again. Not until the afternoon did Hector MacLean, of Sligneach, and Hector MacNiven, of Maol Farm, find her. She lay between the Machar and Loch Staonaig, in a hollow in the chilly moor. She was quite dead, and, except for a silver chain turned black, quite naked. One hand clutched a knife: the other lay between her head and the cold moor. She had died of exhaustion and exposure.

To be precise, it wasn’t just her silver necklace that had turned black – in fact, all her silver jewellery had turned black. When she had been asked about this, she had replied that “this always happened to her jewellery when she wore it”.

According to her death certificate, she died between 10.00pm on 17th and 1.30pm on 19th November 1929, of “exposure to the elements” or “heart failure”. She is buried in a simple grave on the island, which – according to Laura from faeryfolklorist, who took the photo I found on Strange History [linked above] – looks like this:

According to the View From the Hills blog (again):

Netta died with the sum of £424 18s and 6d in her estate — worth roughly £25,000 in today’s money.

The Scotsman, 27th November 1929

This “alien” woman, who dressed in the fashion of the Arts and Crafts movement – with long cape and hand-woven tunic – settled into the house of someone only known as Mrs MacRae. The 33-year-old Fornario spent her time walking the island and in long trances, some of which could last for days.

Initially MacRae was intrigued by her guest’s “mystical practices”, but her interest turned to concern one morning when her lodger appeared in a panic-stricken state. In Francis King’s book Ritual Magic in England, Fornario told her landlady that “certain people” were affecting her telepathically. MacRae was particularly alarmed to see her silver jewellery had turned black overnight.

Fornario was determined to get off the island, but after hastily packing her belongings she appeared to have second thoughts and decided to remain.

The next day, 12 November 1929, she rose early and left the house. The alarm was raised when she failed to appear and two days later her near-naked body was found on isolated moorland.

No police investigation was carried out as the presiding physician noted the cause of death as heart failure from exposure. This explanation has never satisfied Ron Halliday, a psychic investigator and author of Evil Scotland who thinks the death should have been properly investigated.

Her unclothed body was lying on a large cross which had been cut out of the turf, apparently with a knife which was lying nearby.

There were other newspaper reports of her death, e.g.:

* “Iona Mystery – London Woman Found Dead. Mysterious Circumstances.” Glasgow Herald (27th November 1929).

* “Fate of an Iona Visitor – London Woman Found Dead.” Oban Times (30th November 1929).

As Usual, My Rationalist Account

The reason why her silver jewellery turned black was almost certainly because of acidosis – i.e. that her body acidity was particularly high. This is a condition surprisingly common in Type 1 diabetes, where it is called diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA). Even though Type 1 diabetes usually first presents either in young children or in mid-teens, a surprisingly large number (~25%) of cases present in adults: it can also be triggered by stress, changes in environment, etc.

Even though her father was a doctor, she believed (as a young woman) that she was able to cure others telepathically: so I would suggest that she perhaps wasn’t really the kind of person who would sit themselves down in front of a general practitioner to talk about her health issues. Hence it would not surprise me at all if she was suffering from Type 1 diabetes, and that this was largely what her trip to Iona was all about – to try to harness the power of fairy magick to heal herself, even though (as MacGregor describes) she was clearly becoming increasingly unwell.

Had she always been unwell? Even though (the wonderfully flaky) Dion Fortune believed that her friend Netta had died of some kind astral excess or psychic attack, she did concede that perhaps:

She was not a good subject for such experiments, for she suffered from some defect of the pituitary body.

Dead on a chilly Scottish moor in November, naked apart from a silver chain and a knife? Once she reached Iona, far from London’s hospitals, that would seem to me to be how her life would inevitably come to an end. Really: if you tell Fornario’s story like that, there doesn’t really seem to be any other route it could have taken.

Netta Fornario In Art

Dedemia Harding was, it has to be said, more than a tad miffed that her research into Fornario had (she believed) been co-opted by playwright Chris Lee and turned into a play – The Mysterious Death of Netta Fornario – that toured Scotland. “The Gothic tale of magic, madness, murder and mystery is a stylish production inspired by true events on the Isle of Iona.” There’s an interview with Chris Lee here.

But this was not the first artistic reinterpretation of Fornario’s death. Going back to 1952, “An Iona Anthology” by Marian McNeill (according to the Strange History blog again)…

[…]tells of a lady visitor who fell victim to the fairies of the fairy hill on Iona. She apparently slipped out one night to the fairy hill naked carrying only a knife with which to open the hill, and she was found dead in the morning beside the fairy hill (Sithean Mor, it’s just by the road to Machair – aka Angels’ Hill where Columba spoke with the angels). According to the story she was buried at Reilig Odhrain.

This is immediately followed by the “Ballad of lost ladye” by Helen Cruickshank (the words are online here, where you can also buy the music), which describes “[t]he unexplained discovery of the body of a visitor in the early morning beside the Sithean Mor (great fairy mound) on the small, lovely and historic island of Iona”.

But What Of Her Letters?

There are plenty more places where people have discussed Fornario’s death online: Reddit (of course), and Fortean Times (did you ever doubt it?).

There is also Chapter 17 of Classic Scottish Murder Stories online, which brings together yet more strands. e.g. “Richard Wilson quotes from the Glasgow Bulletin a report which describes the body as lying in a sleeping posture on the right side, the head resting on the right hand. A knife was found a few feet away. There were a few scratches on the feet […]. Otherwise, there were no marks on the body.

But the part of the whole story which I’d like to know more about appeared in the Oban Times article (which I haven’t actually seen, but would like to). There, it was reported (according to here, and many other places) that “a number of letters of ‘strange character’ were also taken by the police, who passed them on to the Procurator-Fiscal for ‘consideration’.”

What were these? If there was a cipher mystery angle to this, I’d certainly like to know it. Might – as with the Somerton Man – a local paper have taken any photographs of these letters? Perhaps one day we’ll find out. Just asking. 🙂