It turns out that we can develop the hypothesis that André Bernardin Nageon de l’Estang was in fact Bernardin Nageon de l’Estang very much further than at first seems possible.

For a start, if the two men were indeed one and the same person, I think we can (putting all the pieces together) significantly narrow the range of possible historical dates during which the Will (BN1) and letter (BN2) were written.

Because André Bernardin’s second son André Ambroise was born on 1st October 1745, and his first son Jean Bernardin died on the 16th February 1745 (at the age of only seven months), his (probable) enlistment to La Bourdonnais’ fleet in April/May 1745 would have been at a time when he had no male heir of his own. (His wife may well not have yet realized that she was pregnant with their second child.)

As a result, it seems perfectly conceivable that he would in that context leave his precious pirate treasure cache and half-lot of land in Grand Port to a male relative. But who was Bernardin’s ‘neveu’ (nephew) Jean-Marie-Justin Nageon de l’Estang?

Jean-Marie-Justin Nageon de l’Estang

The Mauritian records tell us that André Bernardin had only one sibling: his sister Jeanne Marie Nageon de l’Estang. She arrived on Ile de France with their parents in 15th July 1738, and was married in 2nd July 1742 to François De la Cour Pradel. However, there is absolutely no genuine BMD data from the Mauritian archives supporting the much-repeated notion that either she or André Bernardin had a son “Jean-Marie-Justin”.

Yet I suspect that if you read the BN2 letter (addressed to ‘Mon cher Justin’) more closely, it not only doesn’t appear to have been addressed to a tiny child, but also doesn’t appear to have been written to someone living on Mauritius at all:

“Par nos amis influents, fais-toi envoyer dans la mer des Indes et rends-toi à l’île de France à l’endroit indiqué par mon testament.”

This surely only makes sense if it was written to someone far away – someone quite probably in France, I would venture to suggest. And in the context of André Nageon de l’Estang (Senior)’s long-standing connections to the Compagnie des Indes, the “amis influents” could surely only have been senior members of the French East India Company.

But could this (still hypothetical) Jean-Marie-Justin have been remotely old enough to be classed as an “officier de la réserve” in 1745? Given that Jeanne Marie was born on 26th November 1726 (it’s on the bottom left of p.264 in GG4 here), and even if she had a child at (say) thirteen, that child would only have been four or five years old by 1745… too young to be Jean-Marie-Justin, I think.

Hence I have to say that trying to reconstruct a missing Nageon de l’Estang genealogy via Jeanne Marie Nageon doesn’t quite work.

The Missing Brother

Yet there is another alternative that threads an acceptable route through our twisty maze of historical constraints.

The gap between André Bernardin (born 1716) and Jeanne Marie (1726) is quite wide: certainly wide enough for the Nageons to have had other children in the gap. If an otherwise-unknown brother had been born (say) around 1718, and had himself fathered a child at a young age, that child might well have been in some kind of Lorient naval academy by 1745, perhaps being fast-tracked towards the life of an officer, courtesy of the Nageon family’s “influential friends”.

So who was the missing brother? Actually, I strongly believe we already saw him mentioned three times in the page on André Nageon de l’Estang:

Danaé (1728-1730)NAGEON, 3 passagers, embarquée à l’armement, débarquée à Pondichéry le 05/07/1729, D[emois]elle, avec ses enfants, Louis et Jeanne Marie.

Badine (1730-1732) NAGEON, 4 passagers, embarqué à Pondichéry, débarqué à ?, passager pour la France, avec son épouse, son fils et sa fille.

Reine (1732-1733) NAGEON, 4 passagers, embarqué à l’île Bourbon le ?, débarqué à Lorient, sr, avec sa femme et 2 enfants, passager pour la France.

If this is as I suspect it is, this missing brother was Louis Nageon de l’Estang, named here for the first time. Further, I suspect that Louis had died by 1746, because that was when André Bernardin named one of his sons “Louis Noël Nageon de l’Estang”, I suspect in his brother’s memory (the son died in 1756).

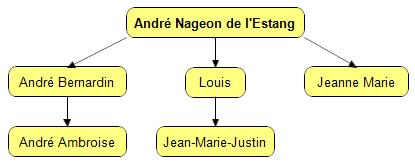

If this all fits together the way it seems (and I really don’t have any more proof than the Danaé’s 1729 passenger list), the relevant section of the Nageon de l’Estang family tree looked like this:

Alas, this is exactly as far as I have been able to reach with the evidence currently available to me. However, perhaps other people will be able to clamber onto my shoulders and use other archival resources to develop this (sketchy, but not entirely hypothetical) narrative yet further.

For example, it might well be possible to determine from the Archives Municipales de Lorient if Lorient had any kind of naval academy for training young officers circa 1745: and if so, what records relating to those institutions are still extant. Similarly, it might well be that André Bernardin Nageon de l’Estang himself – the paterfamilias of the family – might have some personal records in the sprawling historical treasure trove that is the archives of the French Compagnie des Indes.

Or… what do you think?