In Part 1, we saw the outlines of how technology converged with Mauritian treasure hunting mania in the 1920s. But what was that technology, and how ultimately did it link in with Mauritius?

“Listening for Coal”

The person behind the sounding technology was a Mr W. Mansfield, and the story behind it appeared (very appropriately, it has to be said) in The Liverpool Echo, 12th June 1924, page 7, under the title: “Listening for Coal / How Liverpool Inventor Finds Seams / Treasure-Hunters Agog. / Story of Hoard Buried by Pirates“. Tiresomely long title aside, I think the article bears quoting in full:

An invention by Mr William Mansfield, of W. Mansfield and Co., engineers, of Liverpool, by means of which not only the position, but the actual shape, of metalliferous deposits deep in the ground may be indicated on the surface, has aroused widespread interest, especially in the mining industry, for which it was particularly intended to apply.

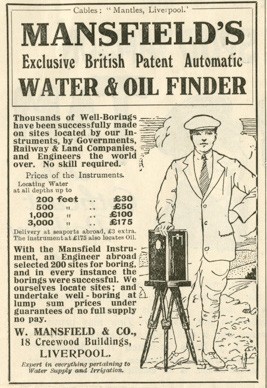

This instrument follows the automatic water and oil finders of the same company, which are being used, it is claimed, with 100 per cent. of success in all parts of the world, and which are supplied on the principle of “no full supply, no pay.”

So, what Mansfield was offering was a kind of echo-sounding technology, which he claimed could be used for many types of prospecting & searching.

In seeking for metals or coal deposits, a very simple electrical device is set up on the surface of the ground, sending a curious musical note through the earth, and a couple of assistants – a man and a boy can carry out the tests – can indicate the presence or absence of what they seek by means of sounders.

Wherever the note is clearly heard the ground is sterile so far as metals or coal are concerned, but when the note diminishes greatly or ceases entirely the indications are that they are walking over deposits. By stepping on and off this cone of partial or complete silence and driving pegs they can outline the form and extent of the deposit, and a simple calculation gives the depth.

News of the invention has greatly increased the enthusiasm of those who believe they know, roughly, where treasure lies buried, and Mr. Mansfield has had many calls from such people.

One treasure hunter had the instrument tested on a piece of ground in Cheshire, where a quantity of metal was buried some twelve feet below a ploughed field. Two men who were entirely ignorant of the position of the “treasure” located the place with precision by means of the automatic finder.

The treasurer[sic]-hunter bought the instrument, and he and a party have taken it to the Spanish Main confident that if they don’t find the doubloons they seek it will be because they are not there.

OK so far: but it’s the final section below that’s arguably the most interesting, because it makes a direct link to Mauritius a couple of years before Captain Russell travelled there (on his doomed treasure hunt):

Mr. Mansfield told an “Echo” reporter that it was child’s play to find a chest of metal a few feet down, and he was too busily occupied with the serious work of which the apparatus was capable to accept all the offers he received to join in expeditions for the discovery of hidden gold and silver which might not exist except in the minds of the seekers.

A letter from the magistrate on the island of Mauritius, in the Indian Ocean, is being looked into, however.

This gentleman, Mr. H. E. Desmarais, and a number of influential friends believe there is £30,000,000 worth of treasure buried on the island, representing booty seized by pirates from British and Spanish vessels well over a hundred years ago.

The proposal made to Mr. Mansfield is that he should locate the treasure for them, and receive a quarter of the find.

In view of the influential backing, Mr. Mansfield is making inquiries. As he points out, if nothing is found, a one-fourth share would not go far to meet his expenses in going out to Mauritius!

By the way, who was H. E. Desmarais?

The above article refers to H. E. Desmarais as a “magistrate”: and indeed Google helpfully supplies links where H. E. (Henri Eugène) Desmarais appears in the Colonial listings as Moka Magistrate for Mauritius (with a salary of 7,000 rupees in the 1890s), having been first appointed there on 1st August 1884.

A family tree on MyHeritage says that Desmarais was born 11 March 1843, and died 22 August 1928. He married Wilhelmina Sophia Henriette Ferdinandine Dancker on 2nd September 1868 in Melbourne: they had ten children. He was the third son of Jean Baptiste Evenor Desmarais, of Port Louis, Mauritius, who himself had been an attorney-at-law. His own law training was as a student of the Middle Temple (18th August 1863): he was called to the bar 30th April 1866.

There is a (paywalled) mention in Alfred North-Coombes’ (1971) book “The Island of Rodrigues” that suggests one of Desmarais’ early appointments was as Rodrigues’ Police Magistrate in 1876.

And finally: in the 1922 Blue Book of the Colony of Mauritius, H. E. Desmarais was listed as receiving (as a retired District Magistrate) a 4,216 rupee pension (79%) since 1913, having then retired “of Old Age”.

All in all, it seems entirely reasonable that Desmarais would have been a member of the Klondyke Syndicate. Incidentally, the mention of his “influential friends” was without doubt a heavy-handed (and deliberate) reference to the “Par nos amis influents, fait toi envoyer dans la Mer des Indes et rends-toi à l’Isle de France, à l’endroit indiqué par mon testament” sentence that appears in letter BN2.

W. Mansfield’s Company & Technology

The 1914 “Who’s Who In Business” includes the following description of W. Mansfield’s company:

Mansfield, W., and Co. Consulting Engineers and Well Boring Engineers, Creewood Buildings, Brunswick Street, Liverpool. Hours of Business: 9.30 a.m. to 6 p.m. Established in 1900 by W. Mansfield, the present principal. Premises: Extensive. Branches: Yenangyat, Promo and Eastern Boronga. Business: Consulting Engineers for many important irrigation projects. Pioneers of Long Staple Cotton Growing in Burma. Owners of Oil and Mineral properties; Well Boring Engineers. Patent: Mansfield’s Automatic Water and Oil Finders. Connection: United Kingdom, Foreign and Colonial. Telephone: No. 1392 Central, Liverpool. Telegraphic Address: ” Mantles, Liverpool.” Codes A B C, Engineering and Private. Bankers: National Provincial Bank of England, Ltd. Mr. W. Mansfield is a member of several Engineering and other Societies. He is interested in Educational questions and has travelled throughout Europe, Asia, and Africa.

From the Grace’s Guide entry on the company, you can see that it was selling its water finder technology by at least 1911. Mansfield’s company later hit the papers in 1931 (10th October, Liverpool Echo, p.13) when a 30-year-old employee sadly got hit on the head and died: and it was still advertising in 1934 (18th July, Liverpool Echo, p.13).

So, what did its metal-finding device look like? Luckily, we don’t have to rely on mere verbal descriptions of Mansfield’s echo-sounding technology, because there are a number of advertisements and articles that contain actual pictures (even if the endorsements that go with them do sound somewhat made-up, it should be added). Here’s a W. Mansfield advert from Chambers’s Journal that sits above an advert for a Dulcitone (which is why the Royal College of Music has a scan of the page on its website):

Coming up next…

In Part 3, I hope to tell a little of the story behind Captain Russell, who led Mansfield’s treasure hunting expedition to Mauritius…

Absolutely fascinating, Nick. I had no idea the technique – basically the same we still use in archaeology today – had such early origins.

It’s essentially the basis for what Tony Robinson calls (rather annoyingly) “the geophys.”

These days we have hand-held instruments which show a lot more than minerals – they map disturbances in the soil and show where even wooden posts, now vanished, were originally sunk, where graves were and so on.

But even as recently as the 80s we had to sink metal pegs into the soil at regular intervals and measure the impulses between them. It was considered a ‘new’ technology then, but it is clearly related to the old ‘echo’ and the sonar. Fascinating stuff.

I was about to ask the question if there is a modern underground search technology, when I saw Diane’s comment. Geologists shouldn’t miss this kind of stuff. Has anyone ever tried to apply this on this island?

Ruby – the sort of work archaeologists do doesn’t need the kind of deep mapping a geologist needs, only maps relative densities. Disturbed soil is less dense, undisturbed soil more so, metals are dense, wood less dense and so on. I suppose you could identify a buried cave, but not one that behind a slab of solid rock.

The very latest instruments of this kind might identify specific minerals, but if so I’ve not seen or used one.

Other technologies serve geology.