I’ve had some interesting emails recently from Patrick O’Neil, who I’m very pleased to report has picked up my long-dropped baton on Mauritian treasure hunting in the period between the two world wars. By uncovering a number of sources I was unaware of (and with only minor assists from me), Patrick has started to reconstruct a side of this story that was previously only hinted at.

“Treasure Hunting in Mauritius”

An article titled “Treasure Hunting in Mauritius” by James Hornell in the 9th April 1932 edition of “The Sphere” (p.57) vividly sets the scene. The famous Mauritian treasure is none other than Surcouf’s, its author asserts, hidden in a cave “on a lonely stretch of coast”, but never retrieved:

A few years ago a plan giving clues to the position of the cave was brought to Mauritius – once a death-bed legacy ! A syndicate [the “Klondyke Syndicate”] of well-known local people was formed to follow up the clues. It was easy enough to identify the narrow gully or gorge in the cliffs up which Surcouf had carried his loot ; two of the stones marked on the plan were located, one with what seemed to have a letter or figure roughly carved upon it. Hope ran high, but now a check was registered ; no trace of a cave could be found ; it was thought that a landslide had taken place covering the mouth. Trial cuts were made here and there but no progress was made, and when the money subscribed ran out, the work ceased.

Hornell goes on to tell us how the search for the treasure then went ‘hi-tech’:

At a later date negotiations were opened with an engineering firm in England, and under agreement of equal shares to each party, an electrical divining instrument, designed to locate metal, was brought into use. Unfortunately the only spot where the pointer became agitated was over a surface of solid rock. From this it was inferred that the landslip had covered the entrance to the cave to a great depth, and that the spot indicated was above the end where the treasure lay. Weary weeks passed in cutting a way down through dense basalt rock of extreme hardness. Ten feet down they went without success ; then to twenty and on to thirty ; at about thirty-five they struck earth, and this raised their hopes to fever pitch. Immediate success was assured – the earth-filled cave was reached at last ! The island authorities were notified and a detachment of armed police went excitedly down to the gully to afford protection, So sure was the engineer of success that a motor lorry was requisitioned to convey the gold and jewels to the bank.

What happened next? Sadly, the dismal punchline is all too easy to predict:

Alas ! Hard rock soon reappeared and the electric indicator still encouraged further effort downwards in the same spot. Two months later when the depth of the shaft had reached over fifty feet I was invited by the engineer to visit the place. I could but admire his tenacity of purpose in face of prolonged disappointment and his patience in laboriously cutting a shaft through virgin rock with chisel and crowbar, afraid as he was to use explosives.

Incidentally, if you’re wondering who the author of this piece was, I’m pretty sure he was the “internationally well known fish expert and colonial adviser based in India” (and former Director of Fisheries in Madras) James Hornell F.L.S. F.R.A.I. (1865-1949), who wrote numerous books on fish, fishing, fishermen, and fishing boats all the way from Britain to Oceania. And did I mention he was interested in fish?

Anyway, even though this helps us glimpse the big picture, we are still left with many questions. For example: where was this site?

“A spot known as Klondyke”

Helpfully, a column in The Daily News of 13th April 1926 reporting on this story describes the location (albeit somewhat inexactly):

The scene of the search is a spot known as Klondyke, on the west coast of Mauritius, in the Black River district, and the treasure, which has come to be spoken of as the Klondyke treasure, is believed to have been secreted there between 1780 and 1800 by the Chevalier de Nageon, a noted privateer.

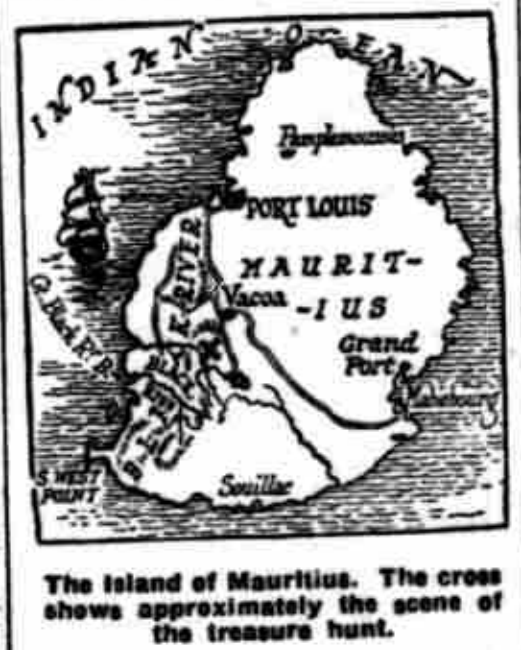

Unlike the version of the article that was reproduced in the Brisbane Telegraph (which I typed up here), this includes a rough-and-ready map, with a piratical “X” to mark the (approximate) spot:

The article continues:

A number of attempts have been made, at intervals since 1880, to find the treasure, and excavations were made in accordance with instructions sent to a Mauritian from one of his relatives in Brittany.

Then the Chevalier de Nageon’s own plan was said to have been found, and a company was formed to begin regular diggings.

Some stonework and other clues tallying with the plan were brought to light from time to time, but nothing else happened, and the shares of the Klondyke Company – held by about a score of persons – became temporarily worthless.

But by the end of last December these shares were selling at 5,000 rupees (about £375) each. This was because Captain Russell had come across new indications which gave rise to the highest hopes.

(Incidentally, has anyone ever actually seen a physical share in the Klondyke Company? I’m sure I’m not alone in wanting to have one framed on my wall.)

There was also a mention at the article’s end that “the native diggers, as I hear today, are feverishly excited concerning yet another treasure, supposed to have been hidden by the same Chevalier de Nageon at Pointe Vacoa, Grand Port“. As you’d of course expect, “(f)abulous figures are mentioned in this latest story”: the Mauritian treasure hunting ‘virus’ is one that constantly mutates…

To be continued…

In Part 2, I’ll go on to look a little more closely at the Liverpool engineering company and their strange machine…