Edith Sherwood very kindly left an interesting comment on my “Voynich Manuscript – the State of Play” post, which I thought was far too good to leave dangling in a mere margin. She wrote:-

If you read the 14C dating of the Vinland Map by the U of Arizona, you will find that they calculate the SD of individual results from the scatter of separate runs from that average, or from the counting statistical error, which ever was larger. They report their Average fraction of modern F value together with a SD for each measurement:

- 0.9588 ± 0.014

- 0.9507 ± 0.0035

- 0.9353 ± 0.006

- 0.9412 ± 0.003

- 0.9310 ± 0.008

F (weighted average) = 0.9434 ± 0.0033, or a 2SD range of 0.9368 – 0.9500

Radiocarbon age = 467 ± 27 BP.

You will note that 4 of the 5 F values that were used to compute the mean, from which the final age of the parchment was calculated, lie outside this 2SD range!

The U of A states: The error is a standard deviation deduced from the scatter of the five individual measurements from their mean value.

According to the Wikipedia radiocarbon article:

‘Radiocarbon dating laboratories generally report an uncertainty for each date. Traditionally this included only the statistical counting uncertainty. However, some laboratories supplied an “error multiplier” that could be multiplied by the uncertainty to account for other sources of error in the measuring process.’

The U of A quotes this Wikipedia article on their web site.

It appears that the U of Arizona used only the statistical counting error to computing the SD for the Vinland Map. They may have treated their measurements on the Voynich Manuscript the same way. As their SD represents only their counting error and not the overall error associated with the totality of the data, a realistic SD could be substantially larger.

A SD for the Vinland map that is a reasonable fit to all their data is:

F (weighted average) = 0.9434 ± 0.011 ( the SD computed from the 5 F values).

Or a radiocarbon age = 467 ± 90 BP instead of 467 ± 27 BP.

I appreciate that the U of A adjust their errors in processing the samples from their 13C/12C measurements, but this approach does not appear to be adequate. It would be nice if they had supplied their results with an “error multiplier”. They are performing a complex series of operations on minute samples that may be easily contaminated.

I suggest that this modified interpretation of the U of A’s results for the Vinland Map be confirmed because a similar analysis for the Voynich Manuscript might yield a SD significantly larger than they quote. I would also suggest that your bloggers read the results obtained for 14C dating by the U of A for samples of parchment of known age from Florence. These results are given at the very end of their article, after the references. You and your bloggers should have something concrete to discuss.

So… what do I think?

The reason that this is provocative is that if Edith’s statistical reasoning is right, then there would a substantial widening of the date range, far more (because of the turbulence in the calibration curve’s coverage of the late fifteenth century and sixteenth century) than merely the (90/27) = 3.3333x widening suggested by the numbers.

All the same, I’d say that what the U of A researchers did with the Vinland Map wasn’t so much statistical sampling (for which the errors would indeed accumulate if not actually multiply) but cross-procedural calibration – by which I mean they experimentally tried out different treatment/processing regimes on what was essentially the same sample. That is, they seem to have been using the test as a means not only to date the Vinland Map but also as an opportunity to validate that their own brand of processing and radiocarbon dating could ever be a pragmatically useful means to date similar objects.

However, pretty much as Edith points out with their calibrating-the-calibration appendix, the central problem with relying solely on radiocarbon results to date any one-off object remains: that it is subject to contamination or systematic uncertainties which may (as in Table 2’s sample #4) move it far out of the proposed date ranges, even when it falls (as the VM and the VMs apparently do) in one of the less wiggly ranges on the calibration curve. Had the Vinland Map actually been made 50 years later, it would have been a particularly problematic poster (session) child: luckily for them, though, the pin landed in a spot not too far from the date suggested by the history.

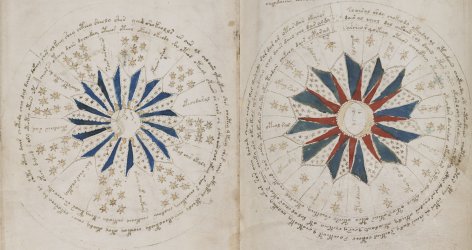

By comparison, the Voynich Manuscript presents a quite different sampling challenge. Its four samples were taken from a document which (a) was probably written in several phases over a period of time (as implied by the subtle evolution in the handwriting and cipher system), and (b) subsequently had its bifolios reordered, whether deliberately by the author (as Glen Claston believes) or by someone unable to make sense of it (as I believe). This provides an historical superstructure within which the statistical reasoning would need to be performed: even though Rene Zandbergen tends to disagree with me over this, my position is that unless you have demonstrably special sampling circumstances, the statistical reasoning involved in radiocarbon dating is not independent of the historical reasoning… the two logical structures interact. I’m a logician by training (many years ago), so I try to stay alert to the limits of any given logical system – and I think dating the VMs sits astride that fuzzy edge.

For the Vinland Map, I suspect that the real answer lies inbetween the two: that while 467 ± 27 BP may well be slightly too optimistic (relative to the amount of experience the U of A had with this kind of test at that time), 467 ± 90 BP is probably far too pessimistic – they used multiple processes specifically to try to reduce the overall error, not to increase it. For the Voynich Manuscript, though, I really can’t say: a lot of radiocarbon has flowed under their bridge since the Vinland Map test was carried out, so the U of A’s processual expertise has doubtless increased significantly – yet I suspect it isn’t as straightforward a sampling problem as some might think. We shall see (hopefully soon!)… =:-o