While searching Gallica just now to try to see if Charles de la Ronciere had donated his personal papers to the Bibliotheque Nationale (TL;DR: I didn’t find anything, but maybe something is there), I noticed that it had a digital copy of (what was almost certainly) de la Ronciere’s last book, (1941) “Explorateurs et pionniers français“. I had a quick look: and was both surprised and delighted to find that it included (on pages 26-27) a section discussing his previous book.

Here’s my translation of these two interesting pages, followed by the original French (which doesn’t seem to be anywhere on the Internet). Enjoy!

My (free and easy) translation

The mysterious pirate: story of a hidden treasure in the Seychelles Islands.

“I would like to see a copy of The Clavicles of Solomon, to use its magical characters to help decipher a cryptogram left by a pirate.” This was the request made to the Bibliotheque Nationale by a reader from a distant region of Africa. She explained to me that, on a certain island in the Indian Ocean, in the Seychelles, one could see sculptures and rock engravings emerging from the waves during high tides, or from the ground when large trees fell, which corresponded to the signs in the cryptogram. Thus, a shape in the form of a monster’s eye appeared in this document; this same shape also appeared on M[auritius]. Near there, three bodies had been found, two of them with a gold ring on the left ear, pirate-style; the third was buried as if he had been stoned for having murdered his companions.

– “What language is the cryptogram in? I asked.

– It can be read in French.

– Do you have any idea of the name of the pirate who wrote it?

– None. Could you open an investigation into this?” asked the reader.

And so my investigation began. Was it plausible that a bandit would use a cryptogram? And was it admissible that he used a desert island as a ‘safe deposit box’? No doubt about it. In 1690, on his way to the Indian Ocean, a sea captain called Duquesne-Guitton on Ascension Island left inside a bottle – like a sort of Post Office – a list, in columns, of pounds, shillings and pence for one of his stashes (e.g. gold, 310 pounds, 10 shillings, 6 d): see the New French Dictionary of Father Charles Payot, on page 310, 10th line, 6th word.

It was also the habit of bandits to bury their loot in desert islands. The Golden Scarab by Edgar Poe is merely a fictionalized version, with a skull in a tree as a landmark, of the discovery made, in 1699, of the treasures buried on Gardiner Island by the pirate William Kidd, comprising bars of money, bags of gold and precious stones. Pirates buried their loot ten feet underground so that probes by spears and pertuisanes [?] could not detect it. Gold and precious stones were hidden by the sea; the money and what feared humidity were buried between two calabashes inside the desert island, in a very dry place. Remember this duality of the deposit. It will soon have considerable importance.

The history of French pirates in the Indian Ocean was far from banal!

A Provençal rogue by the name of Misson gained a singular fortune in the Comoros Islands. Wearing a gold-embroidered red coat of the royal princes, and a jewel-encrusted dagger on his belt, he had married the daughter of the Queen of Anjouan, with nails dyed red, eyebrows and eyelashes dyed blue. And with the help of the Anjouanese, he founded a republic of pirates. In the north of Madagascar, there is a deep bay to which a narrow neck gives access. On both sides of the Diégo-Suarez strait arose, under the direction of Misson, the strange city of Libertalia, where all the races formed one people, the Liberi. “Hsis High Excellence the conservative” is the title that Misson gave himself, as he directed its destinies, with the assistance of a Parliament, presided over by the defrocked Neapolitan priest Caraccioli. In this parliament, each group of voters, French, Portuguese, English, Dutch, Negroes or Arabs from the Comoros, appointed a delegate. The ships and sloops of the Libertalian Republic, commanded by the Englishman Thomas Tew, were armed half with blacks, half with whites. In 1705 and 1706, they stoked up trouble for our settlers on Bourbon Island (now known as Reunion). But this Babel of races shared the same the fate as the original Tower of Babel. The ships perished in a typhoon. Then, invading Libertalia at night, the Malagasy massacred the population. The republic of the bandits perished without leaving a trace.

The problem of the pirate who buried a fortune in the Seychelles Islands remained unsolved.

The small island of Sainte-Marie, just off the coast of Madagascar, was another pirate den. The virtuoso of the genre was a Calaisian, Olivier Le Vasseur, nicknamed La Buse. Among the ships he kidnapped was a Portuguese ship, coming from Goa, loaded with millions, which was bringing back to Portugal the viceroy of India and the archbishop of Goa. Diamonds were in abundance there, so much so that each of the bandits, of whom there were hundreds, received forty-two diamonds for their share. One thug, having received only one magnificent diamond, crushed it to have the same number of jewels as the others. This whole event took place in 1724. La Buse later dared to ask the governor of Bourbon Island (Reunion) for an amnesty, by returning some of the Archbishop of Goa’s sacred vases. His request was denied. Had he not kidnapped a ship from the Compagnie des Indes, to which Bourbon Island belonged? And in 1730 he atoned. Having been captured by a captain of the Compagnie, he was brought to Bourbon, then tried and hanged. Legend has it that when he went up to the gallows, he held out the cryptogram, saying: “To him who finds it.” La Buse, living on Sainte-Marie, no longer had the fruits of his plunders: he had therefore hidden them somewhere. And from 1724 to 1730, he had plenty of time to act. Back then, the Seychelles Islands were deserted: it was only in 1742 that Mahé de La Bourdonnais took possession of them.

Anyway, now listen to the rest of the story. My own investigation had led to my writing a book: “The Mysterious Filibuster: Story of a Hidden Treasure“. My friend Lenotre from the French Academy gave an excellent account of it in Le Temps, which by chance ended up being read in Cameroon by an islander from the Seychelles. The islander then sent his mother to me.

– “Could it have been that the treasure was found on our land? asked Mrs. D[…] She owns Silhouette Island in the Seychelles.

– No, Madam.

– I had, monsieur, another property on M[auritius], in Coëtivy. One day, a ship dropped anchor in the nearby cove…

– Anse des Forbans, I interrupted.

– The next day, it had disappeared. But instead of a sort of big pole-shaped rock, there was a big hole….

– Nine to ten feet deep.

– We could see at the bottom the traces left by two urns.

– Two water gourds, I interrupted again. And the bottom was very dry?

– Very dry.

– Well, madame, it was [probably] a pirate’s hiding place that was emptied, the kind of one that contained objects sensitive to humidity, such as silver or cashmeres, but what do I know?”

But then a conclusion was necessary. The habit of the bandits was to make two separate kinds of hiding places, where the gold and the precious stones would be buried close to the water’s edge: sculptures and rock engravings would be points of reference, although the coast has subsided since then and may well have buried these caches itself. May Madame S[avy] now detect their location, courtesy of the radiological dowsing of Abbot Mermet!

The original text

Le flibustier mystérieux : histoire d’un trésor caché aux îles Seychelles.

« Je voudrais voir les Clavicules de Salomon pour achever de déchiffrer, au moyen de ses caractères magiques, le cryptogramme laissé par un forban. » Telle était la demande formulée à la Bibliothèque Nationale par une lectrice venue d’une région lointaine de l’Afrique. Elle m’expliqua que, dans certaine île de l’Océan Indien, aux Seychelles, on voyait surgir du sein des flots, lors des grandes marées, ou du sol, lors de la chute de grands arbres, des sculptures at des gravures rupestres, qui correspondaient aux indications du cryptogramme. Ainsi, un œil du monstre était spécifié dans ce document ; et il existait dans l’île M… Près de là, on avait trouvé trois corps, deux d’entre eux ornés d’un anneau d’or à l’oreille gauche, selon l’habitude des forbans ; le dernier, enfoui, comme s’il avait été lapidé pour avoir assassiné ses compagnons.

« En quelle langue est le cryptogramme ? demandai-je.

– Il se lit en français.

– Avez-vous quelque idée du nom du forban qui l’a écrit ?

– Aucune. Pourriez-vous ouvrir une enquête là-dessus ? » me demanda la lectrice.

Et mon enquête commença. Était-il plausible qu’un forban usât d’un cryptogramme ? Et il était admissible qu’il prît pour coffre-fort une île déserte ? Aucun doute là-dessus. Dans le ventre d’une bouteille – qualifiée Bureau de la Poste – à l’île de l’Ascension, un capitaine de vaisseau, Duquesne-Guitton, en route pour l’océan Indien, laissait, en 1690, une liste, en colonnes, de livres sterling, de shillings et de pence à destination d’une de ses conserves. Or, 310 l. 10 s. 6 d. par exemple, devaient se lire ainsi : prenez le Dictionnaire nouveau français de Père Charles Payot, à la page 310, 10e ligne, 6e mot.

C’était également l’habitude de forbans d’ensevelir leur butin dans des îles désertes. Le Scarabée d’or d’Edgar Poe n’est que l’histoire romancée, avec crâne dans un arbre comme repère, de la découverte faite, en 1699, des trésors enterrés dans l’île Gardiner par le pirate William Kidd, barres d’argent, sacs d’or et de pierreries. Les forbans ensevelissaient leur butin à 10 pieds du sol, afin que la sonde avec les lances et pertuisanes ne pût le déceler. L’or et les pierres précieuses étaient cachés au bord de la mer ; l’argent et ce qui craignait l’humidité étaient inhumés entre deux calebasses à l’intérieur de l’île déserte, dans un endroit très sec. Retenez bien cette dualité du dépôt. Elle aura tout à l’heure une importance considérable.

L’histoire des forbans français de l’océan Indien n’avait rien de banal.

Un forban provençal du nom de Misson avait eu, aux îles Comores, une singulière fortune. En habit rouge brodé d’or des princes royaux, le poignard incrusté des pierreries à la ceinture, il avait épousé la fille de la reine d’Anjouan, aux ongles teints en rouge, aux sourcils et aux cils teints de bleu. Et avec l’aide des Anjouanais, il avait fondé une république de forbans. Au nord de Madagascar, il est une baie profonde à laquelle donne accès un étroit goulet. Des deux côtés du goulet de Diégo-Suarez s’éleva, sous la direction de Misson, l’étrange cité de Libertalia, où toutes les races no formaient qu’un peuple, les Liberi. « Su Haute Excellent le conservateur », c’est le titre que se donnait Misson, en dirigeait les destinées, avec le concours d’un Parlement, présidé par le prêtre napolitain défroqué Caraccioli. Au Parlement, chaque décurie d’électeurs, Français, portugais, Anglais, Hollandais, Nègres ou Arabes des Comores, nommait un délégué. Vaisseaux et sloops de la république des Liberi, commandés par l’Anglais Thomas Tew, étaient armés moitié do Noirs, moitié de Blancs. Ils causèrent de l’iniquiétude, en 1705 et 1706, à nos colons de l’île Bourbon, l’île actuelle de la Réunion. Mais cette Babel de races eut le sort de la tour de Babel. Les vaisseaux périrent dans un typhon. Envahissant de nuit Libertalia, les Malgaches en massacrèrent la population, La république des forbans avait vécu sans laisser de traces.

Le problème du flibustier qui aurait enseveli une fortune aux îles Seychelles, restait entier.

La petite île Sainte-Marie, sur la côte de Madagascar, était un autre repaire de forbans. Le virtuose du genre tait un Calaisien, Olivier Le Vasseur, surnommé La Buse. Parmi les navires qu’il enleva se trouvait un vaisseau portugais, venant de Goa, chargé à millions, qui ramenait en Portugal de vice-roi de l’Indes et l’archevêque de Goa. Les diamants y étaient à foison, si bien que chacun des forbans, qui étaient des centaines, reçu quarante-deux diamants pour sa part. Une brute, n’en ayant touché qu’un, un diamant magnifique, le broya pour avoir le même nombre de joyaux que les autres. Le fait se passait en 1724. La Buse osa demander au gouverneur de l’île Bourbon (la Réunion) l’amnistie, en restituant quelques vases sacrés de l’archevêque de Goa. Il fut évincé. N’avait-il pas enlevé un navire de la Compagnie des Indes, dont relevait l’île Bourbon. Et en 1730, il expia. Cpturé par un capitaine de la Compagnie, il fut amené à Bourbon, jugé et pendu. Le légende veut qu’en montant au gibet, il aurait tendu le cryptogramme, en disant : « A celui qui trouvera. » la Buse, à Sainte-Marie, n’avait plus le fruit de ses rapines : il les avait donc cachées quelque part. Et de 1724 à 1730, il avait eu tout le temps d’agir. Les îles Seychelles étaient alors désertes. Ce n’est qu’en 1742 que Mahé de La Bourdonnais en prit possession.

Écoutez la suite. De l’enquête à laquelle je m’étais livré, j’avais tiré un volume : le Flibustier mystérieux : histoire d’un trésor caché. Mon ami Lenotre, de l’Académie française, en fit, dans le Temps, un excellent compte rendu, qui tomba par hasard, au Cameroun, sous les yeux d’un insulaire des Seychelles. L’insulaire me dépêcha sa mère.

– « Serait-ce chez nous que se trouve le trésor ? me demanda Mme D… Je possède, aux Seychelles, l’île Silhouette.

– Non, madame.

– J’avais, monsieur, une autre propriété dans l’île M…, à Coëtivy. Un jour, un navire jeta l’ancre dans l’anse voisine…

– L’anse des Forbans, interrompis-je.

– Le lendemain, il avait disparu. Mais à la place d’une sorte de grande perche, il y avait un grand trou….

– De neuf à dix pieds de profondeur.

– On voyait au fond la trace laissées par deux urnes.

– Deux calebasses, interrompis-je encore. Et l’endroit était très sec ?

– Très sec.

– Eh bien, madame, c’est une cachette de forban qui a été vidée, celle qui contenait des objets craignent l’humidité, argent, cachemires, que sais-je ? »

Mais alors s’imposait une conclusion, L’habitude des forbans étant de faire deux cachettes, l’or et les pierreries seraient biens ensevelis au bord de la mer : sculptures et gravures rupestres seraient bien des points de repère, encore que la côte se soit affaissée depuis lors et les ait souvent elles-mêmes ensevelies. Puisse madame S… déceler le gîte, grâce a la radiesthésie de l’abbé Mermet !

I’m more familiar with the Lesser Key of Solomon, or Lemegeton Clavicula Salomonis, esp the Ars Goetia (and if I hear one more so-called expert on the occult on YouTube pronouncing it Go-eesha I will scream – it’s Go-ettia!), as translated by SL Macgregor Mathers and published by Aleister Crowley (him again – he also drew some dirty pics of a few of the 72 demons/spirits constrained by King Solomon in his bronze vessel!), but in what sense could the (Greater) Key of Solomon, a 14th or 15th century Italian Renaissance grimoire, “help decipher a cryptogram left by a pirate”?. Guess I’ll have to look into A. E. Waite’s 1898 Book of Black Magic and of Pacts (or The Book of Ceremonial Magic) which is stuck in my huge books to read pile.

My French is far too rudimentary to read the original so I’ll have to rely on Mr P’s (free and easy) translation.

Pertuisanes.

“Spontoons may have evolved from earlier spear-like weapons called pertuisanes or partisans. The partisan had a large blade, sharp on both sides. The blade was wider at the bottom, where twin symmetrical blades of various shapes sprouted from the sides. Rather blurry lines separate the spontoon and a number of other spear-like staff weapons. There were hybrids known as “partisan spontoons,” and some 18th-century European accounts refer to officers’ weapons as partisans rather than spontoons. Other sources refer to spontoons as “half-pikes,” and some simply call them spears.

Never primarily intended for combat, the spontoon was introduced to armies as a new symbol of officer rank. They appeared in France in 1690, with new military regulations requiring infantry officers to carry an espontoon. After 1710, junior officers carried fusils instead, but senior officers retained their spontoons until the French Army abandoned them in 1756.”

See: https://warfarehistorynetwork.com/article/halberds-and-spontoons/

Always like to see Edgar Allen Poe get a mention and there was an interesting In Our Time discussion of the great man with Melvin Bragg and his three sages recently – check it out on BBC Sounds. Hugely influential writer although many literary types, including our American friends, used to be terribly sniffy about him, and some renowned critics – John Sanders for example – still are. No Poe, no Baudelaire, no Sherlock Holmes, no Treasure Island, no HP Lovecraft, maybe no Alfred Hitchcock.

Just to remind readers of the cryptogram in The Gold Bug:

” 53‡‡†305))6*;4826)4‡.)4‡);80

6*;48†8¶60))85;1‡(;:‡*8†83(88)

5*†;46(;88*96*?;8)*‡(;485);5*†

2:*‡(;4956*2(5*-4)8¶8*;40692

85);)6†8)4‡‡;1(‡9;48081;8:8‡1

;48†85;4)485†528806*81(‡9;48

;(88;4(‡?34;48)4‡;161;:188;‡?;”

From Wikipedia: “Poe had an influence on cryptography beyond increasing public interest during his lifetime. William Friedman, America’s foremost cryptologist, was heavily influenced by Poe. Friedman’s initial interest in cryptography came from reading “The Gold-Bug” as a child, an interest that he later put to use in deciphering Japan’s PURPLE code during World War II.”

Maybe Bella in the Wych Elm was put there by a pirate “as a landmark” to guide others to some treasure. Anyone fancy a dig up in Worcestershire?

Quelle histoire!! Si j’étais « Madam » je répondrais, « Si je tu parle du mon cul, c’est n’est pas pour ton faire cadeau! » !!

(My best comp school French there…).

Radiological dousing of l’abbé sounds a little hard core as an investigative tactic!! Pray tell, sir, what is it with CM and Abbotts?

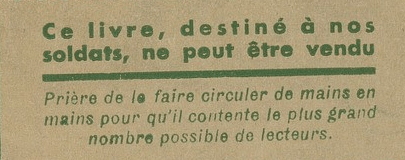

@ Nick – do do you think the original book was in a Legionnaire library? I think a bit of gold could be made with a film about 1940s-50s legionnaires traipsing through misadventures in the Seychelles in search of cryptographic clues & treasures. I’m going to email Claire Denis…

Finally intrigued to the point of asking Audible, found there (free to members)

The Republic of Pirates

Being the True and Surprising Story of the Caribbean Pirates and the Man Who Brought Them Down

By: Colin Woodard

I had no idea La Buse was such a great name. The author speaks of him with genuine awe, and it seems that both pirates and buccaneers of the time did, too.

Since I sat on it for at least a decade, Roncierce gave an interview to one R.S. Fenwick. Milwaukee Post.

The elusive document was done on goat skin, the missing lines are described as a rebus, that’s where you will find the most accurate, not assumptions & conclusions on poe.

The article referenced in the comment above is “R.S. Fendrick. 1934. Cryptogram clue to Pirate Hoard. The Milwaukee Journal, July 15th” although I haven’t found a way to access it through any digital collections. I’m curious to know the contents but doubtful it sheds much light as R.S. Fendrick seems to have mostly written about salacious news of the weird type subjects.

Roncière’s motivation for writing Le Flibustier Mystérieux remains the biggest mystery to me in this whole saga. Perhaps the economic turbulence of the 1930s forced his hand to crank out a few pages for a dime-store publisher, or the rising political chaos of the interwar years left him wanting to provide his country with a few entertaining stories while expressing his pride for French mariners, or maybe this was just a fun creative writing exercise after decades of abstemious writing.

I mostly suspect the latter based on his earlier work which makes it hard for me to believe this was meant to be read as anything other than fiction.

The article as told by ronciere, gives the account of the visit by Rose Savy, the suggestion given to her about being the clavicles of Solomon.

Ronciere did his research & deductions of which pirate it may relate to.

The missing lines as described in the article as a rebus. However as a standalone there is no context.

It does have similarities to others assumptions of Poe. I suspect there is an old shanty/ yarn which is similar prior, yet no record seems to appear.

As for access to article, it was originally accessible before access was denied online

I am highly confident he was the first to understand the cryptogram, to its full extent, I doubt it, partly yes & for whatever reason did not act upon- for whatever reason his status/ position head of manuscripts, politics, who knows.

There is at least a dozen plus articles written at the time in various forms all within a few months, but only this one produced a rebus

As for the journey of the Cabo, as told by the viceroy himself, the events of the storm, damage to Cabo, him being on land & arch bishop on ship as pirates to vessel – that can be found in ‘le Mercury’ may 1722 (that can be accessed online)

As for origins of the pirate – look to ‘Tourcoing’ Nord pas de Calais, his mother came from a neighbouring village, perhaps he used the river ways in his youth that linked to Calais ferrying crops.

As for schooling – there was a school at his time, those records will be somewhere random.

As for relations, streets are named after his ancestors, dig deeper & you’ll find his great grand parents

Hope it helps

Toulouse dit baillon,

If you have the timelines, the contexts & various other understandings, then that article is very relevant, in more ways than one.

As a teaser – from cryptogram

A2FDMEPRNLNIDEU (from memory)

Every letter at start of each line

= A 2 find map run I line I do for you

However, to follow this process would end in flaws.

So, what is the right way(s)?

Mr Pelling almost came close to partially grasping it.

As an additional – to get the fullest character of levasseur, in Cape Town, in the VOC archives is a full assessment done by the governor of the fort at delagoa, Maputo Bay. (The current stone fort ruins is on the same location as the original wooden one in the pirates time. (Google earth) This document describes the main pirates in this legend. Sadly this document has been withdrawn along with countless others & sold.