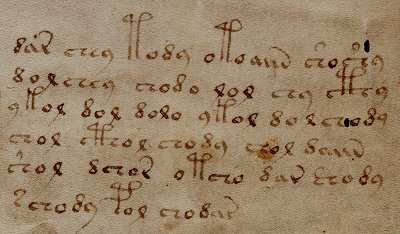

In his 1665 letter to Athanasius Kircher accompanying what we now call the Voynich Manuscript, Johannes Marcus Marci wrote [Philip Neal’s translation]:-

Doctor Raphael, the Czech language tutor of King Ferdinand III as they both then were, once told me that the said book belonged to Emperor Rudolph and that he presented 600 ducats to the messenger who brought him the book. He, Raphael, thought that the author was Roger Bacon the Englishman. I suspend my judgement on the matter.

You be the judge of what we should think about it. […]

All very well: but surely this begs a huge question, one that everyone has seemed content to duck for the last century. Let’s not forget that Raphael Sobiehrd-Mnishovsky de Sebuzin & de Horstein was a lawyer, writer, poet, cryptographer, and even a favourite at the Imperial Court: basically, a smart, super-literate, well-connected cookie. So why on earth did he think this odd manuscript had anything whatsoever to do with Roger Bacon, of all people?

Of course, now that we have a 15th century radiocarbon date for the manuscript, Voynich researchers are a little inclined to be sniffy about Bacon, thinking this mostly a sign of Wilfrid Voynich’s personal folly – or, more specifically, WMV’s antiquarian obsession with finding any link that could be proven between his “Roger Bacon Manuscript” and Roger Bacon himself. Perhaps it was WMV’s burning desire that ultimately claimed poor William Romaine Newbold’s life, drained by his pareidoiliac compulsion to reveal its craquelure shorthand, with his friend Lynn Thorndike then unwillingly laying Newbold’s hopeful nonsense to rest.

But all the same, Roger Bacon is mentioned right there in Marci’s letter: and this is one of the very first things we have that describes the Voynich, as well as the manuscript’s earliest provenance link with Rudolf II’s Imperial Court. So why Bacon? What possible candidate explanations have been put forward?

Actually, surprisingly few of any great credibility, it has to be said. Some people have argued (without great enthusiasm) that the manuscript might possibly be a 15th century copy of a lost work by Roger Bacon. However, its tricky cryptography seems light years beyond Bacon’s era, while the near-complete absence of religious imagery (combined with the nakedness of its ‘nymphs’) also seem sharply at odds with Bacon’s monastic severity, let’s say.

In “The Curse of the Voynich” (2006), I speculated [p.219] that Roger Bacon might have been part of a cover story deliberately planted by the original author. Certainly there is reasonable evidence that the Voynich’s cipher alphabet was consciously constructed to look somewhat archaic to mid-fifteenth century eyes: say, 100 to 150 years older than its physical age. Bacon’s familiarity with Arabic sources and even possibly his (alleged) link with alchemy might then have commended him to the real author as a fake author… back then history was a little more forgiving, let’s say, over such issues as authenticity.

However, a key problem with this hypothesis is that many of the previous objections (the lack of religious imagery, the nymphs) apply just as strongly. Moreover, I’m now fairly sure that Bacon only had alchemical works (falsely) ascribed to him many decades later (around 1590-1600), which further weakens the argument. Hence six years on, I’m not so convinced any more… oh well!

And yet Dr Raphael thought it was Bacon ‘wot dun it’. How can that be? What reasonable explanation might there have been for this otherwise inexplicable lapse of judgement? Well, here’s my 2012 attempt to form an Intellectual History account of all this…

Could it be that the link with Roger Bacon wasn’t in the content of the manuscript but in something to do with Bacon’s Franciscan order? Simply put, might the Voynich Manuscript have been owned by Franciscans? Might it have lived in a Franciscan library? Even more specifically, might it have lived in a Franciscan Library not too far from Lake Constance?

I suspect that the deliberately plain brown habit and white belt of a Franciscan or Capuchin monk would have been an unusual sight at the Imperial Court, where the white and black habits of the Benedictine, Cistercian and Augustinian orders were very much more usual. Please correct me if I’m wrong, but Wikipedia’s list of Imperial Abbeys seems not to contain a single Franciscan friary, monastery or convent.

So, might the messenger bearing the Voynich Manuscript have therefore been a Franciscan monk? If it was, then I think Dr Raphael could indeed have reasonably inferred that the author of the Voynich Manuscript might well have been Roger Bacon: for if it was an enciphered manuscript of the right age from a Franciscan library with an unknown early provenance, Roger Bacon’s authorship could well have been a perfectly reasonable inference, and in fact no less wobbly than most of what has generally been passed off as 20th / 21st century Voynich theorizing.

Hence I’m pretty smitten by this Franciscan Voynich Theory: if true, it would explain Dr Raphael’s testimony in a parsimonious and reasonable way, even if it doesn’t actually help us read the manuscript itself. It may also be the case that the back page (f116v) was a little more readable circa 1610: the presence of what looks like “six pax nax vax ahia maria” interspersed with crosses then might have had far more religious import back then than it does to us moderns.

A reasonable next step might well be to start looking for Franciscan libraries in the Lake Constance area circa 1600-1610: I asked the well-respected Franciscan historian Bert Roest where to look next, and he very kindly directed me to the extensive online list of Works/info on medieval and early modern Franciscan libraries he helps maintain. I should mention quickly that it’s, errrm, a bit big.

Does anyone want to kindly volunteer to trawl through it to compile a preliminary list of candidate Franciscan libraries? For example, Bad Kreuznach, Thuringia, Gottingen, and Frankfurt are all in there, but I suspect that these might all be a little bit too far North, while Fribourg was also perhaps a little too far West. I’m not sure if there are many left! Perhaps this would best be done as some kind of Google Maps overlay?

However, I should caution that real history often turns out to be an unexpected anagram of all the things we suspect: that is, all the right ingredients, but arranged in an order that subtly confounds your expectations and carefully laid plans. Here, the historical ingredients are:

* a Franciscan Library

* Lake Constance (i.e. the Bodensee)

* Rudolf II’s Imperial Court

* a Chinese Whispers-like process whereby the original provenance was forgotten over many decades.

Given all that, I did notice one rather intriguing alternative possibility: Lindau, an Imperial Free City on its own island in the Bodensee. This was formed from the core of a Franciscan Library that was given over to the city in 1528 as part of the Protestant Reformation: it’s now part of the Reichsstädtische Bibliothek Lindau. Once again, do I have any volunteers for looking through the library’s early catalogue?

Really, the question comes down to this: might a representative of the Imperial Free City have taken a strange herbal-like book to Prague circa 1605-1610 from the former Franciscan library in Lindau as a splendidly odd gift for Emperor Rudolf II? Personally, I think it’s entirely possible and – best of all – something that might well be checkable against the historical record. Testable history: it’s something I can’t get enough of! 🙂

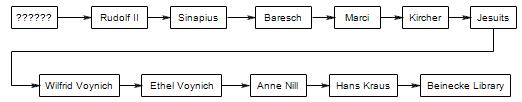

Once upon a time (in 1912) in a crumbling Jesuit college near Rome, an antiquarian bookseller called Wilfrid Voynich bought a mysterious enciphered handwritten book. Despite its length (240 pages) it was an ugly, badly-painted little thing, for sure: but its strange text and drawings caught his imagination — and that was that.

Once upon a time (in 1912) in a crumbling Jesuit college near Rome, an antiquarian bookseller called Wilfrid Voynich bought a mysterious enciphered handwritten book. Despite its length (240 pages) it was an ugly, badly-painted little thing, for sure: but its strange text and drawings caught his imagination — and that was that.