This page describes what can be inferred about the Voynich manuscript from its physical makeup. It summarizes information from several sources (perhaps most notably/notoriously my 2006 book The Curse of the Voynich), and to illustrate the various arguments includes reasonable colour images [derived from the Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library’s colour scans].

(1) The Folio Numbers Are Not Necessarily Correct

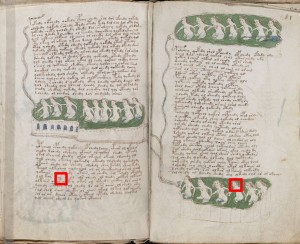

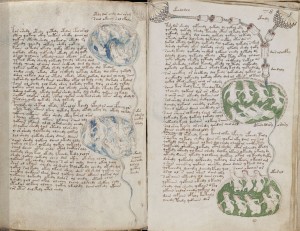

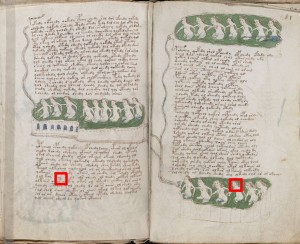

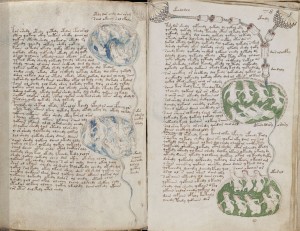

Water flows from the bath on f78v [below left] right under a separate bifolio before reappearing on f81r [below right]. These two pages must therefore have faced each other in the original page layout, and can only sensibly have appeared at the centre of a quire with consecutive folio numbers: and so the present (non-consecutive) folio numbers are plainly wrong.

Also highlighted with red squares in the above pair of images is some red paint contact transfer (going from right to left) that apparently happened while the manuscript was in its alpha [original] state. (They are not aligned perfectly because the manuscript was fully bound when scanned, leading to perspective distortion.)

(2) The Bifolios Are Not Necessarily The Right Way Up

If f78v and f81r originally sat at the centre of the quire (as shown above), what page originally preceded f78r (i.e. which page sat facing f78r, nearer the front of the quire)? If you try every permutation in the water section, I contend that you will find only that one fits perfectly: f84v. Moreover, the two-page layout across f84v [below left] and f78r [below right] uncannily echoes the two-page layout exhibited on f78v and f81r [above]. But really, what clinches the case that these pages did originally face each other is the unusual “pineapple”-like fruit at the top, which appears on both of these pages (even symmetrically mirroring each other in the top middle!), but nowhere else in the manuscript.

However, because f84v as currently bound appears right at the back of the quire, this means that the bifolio containing it was bound in back to front relative to its initial orientation (i.e. the spine of the bifolio was flipped over before it was bound in, so what was initially at the front of the bifolio ended up at the back), and hence that whole bifolio is now upside down.

What is particularly interesting about this visual symmetry between page layouts is that it implies that the drawings in the manuscript had originally been laid out not arbitrarily or randomly (as they now appear), but instead according to some kind of consistent design aesthetic. I take this as a strong sign that we should be looking in the Voynich Manuscript to reconstruct a sense of order and purpose that has been scrambled by historical happenstance.

(3) The Quire Numbers Are Not Necessarily Correct

If f84v (which has Q12’s quire number on its bottom right corner) originally preceded f78r, this implies that the quire numbers were added after the page order in Q12 had been scrambled (nobody would have placed a quire number in the middle of a quire). Furthermore, quire numbers (particularly higher ones such as Q19 and Q20) appear to have been added by later hands, so may well be unreliable for quite different reasons.

(4) The Bindings Are Not Necessarily Correct

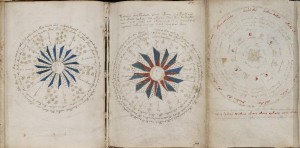

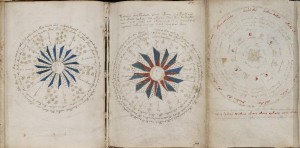

Many years ago, John Grove pointed out that while the first wide sexfolio of Q9 had originally been bound between f67r1 [below centre] and f67r2 [below right] (you can clearly see the binding marks laid out flat on the page), it had subsequently been rebound between f68v [below left] and f67r1 [below centre] after the quire numbers had been added (and before the folio numbers had been added). The centre page [f67r1] was originally at the back of the quire (which is where the quire number would have been added), but after the subsequent binding the same page ended up at the front of the quire (which is where the folio number was added) – all of which is why it ended up with both foliation and a quire number on the same page.

Moreover, the circular drawing on f68v (“sun-face calendar”) very closely echoes the circular drawing on f67r1 (“moon-face calendar”): this gives powerful support to the idea that these two pages originally sat next to each other. Back in July 2002, John Grove wrote: “I’m beginning to thank that oaf for fouling up the numbering” – it is indeed true that these kind of mistakes help us to understand what happened to the VMs pre-1600 in a way that the archival evidence has so far been unable to do.

Furthermore, my suspicion is that there was a simple practical reason for what happened with these pages. In its original arrangement, this sexfolio had one page on one side of the binding and five pages on the other, which would have been somewhat impractical for handling. By rebinding it along a different boundary between pages, that oaf may well have helped to keep the manuscript intact – no bad thing, really.

(5) The Quires Are Not Necessarily In The Correct Order

I have argued that the two pharma quires (Q15 and Q19) appear to have had their order reversed, because the jar sequence seems to flow far more naturally from the end of Q19 to the pharma bifolio in Q15 than the order in which they now appear.

(6) The Quire Contents Are Not Necessarily Correct

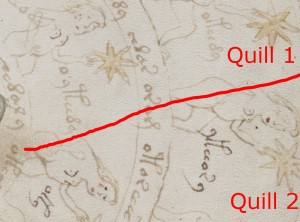

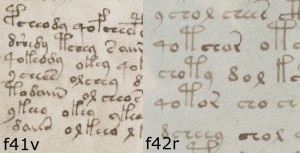

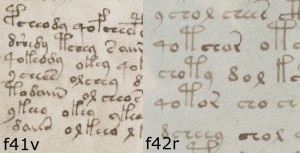

If you compare f41v and f42r in Q6, you’ll notice markedly different handwriting – the first is tight, compact, slightly right-leaning while the second is gentle, open, and slightly left-leaning (though whether this implies different authors, or different quills and/or different inks and/or times is a separate matter). This would be consistent with the basic codicological inference that the manuscript’s bifolios have been shuffled largely at random.

As an alternative explanation, Glen Claston argues that the bifolios might plausibly have been deliberately shuffled by the author (perhaps later in life) to match some change in organizational plan (say, from alphabetical order to thematic order). However, because the two halves of each bifolio are stuck together, I would point out that you can’t really restructure codices to any significant degree unless you physically divide each bifolio, and there’s (as yet) no evidence that this happened here.

(7) The Paints And Colours Used Are Not Necessarily Original

There’s been a long and spirited debate about this one. The short version is simply this: a significant number of Voynich researchers have come to believe that paint was added in several waves, with a small set of washy (possibly organic?) paints added early, and a larger set of heavy (possibly inorganic?) paints added later. Critically, the heavy blue paint appears (in a good few places) to have transferred across to facing pages within the current binding order, and with a very distinctive (and unusual) drying pattern. To me, this clearly indicates that the paint was added after the pages had been bound and then contact transferred while still drying (though Glen Claston argues that some unknown bacterial mechanism may have caused them to transfer many years later in conjunction with localized water damage).

As further evidence to support the argument, I would point to the markedly different paints on the f84v and f78r pair [section (2) above] and on the f102v and f88r pair [section (5) above]. Really, it comes down a binary choice: you either have to accept that the codicological evidence points to several misbinding (non-original) owners, or you have to reject the whole lot of it, period.

All in all, Glen spent a long time utterly convinced (as was Prescott Currier, for the most part) that the current page order, quire numbering and page appearance we now see all strongly reflect the author’s intentions: of course, this position is entirely possible – but I have yet to see a single piece of codicological evidence that supports it.

(8) One Day, We’ll Reconstruct The Page Order (But Not This Week)

From (2)-(8) above, it should be reasonably clear that what we are looking at in the VMs is not the original page order, or even the original page state: and that even the (apparently 15th century hand) quire numbering is an unreliable guide to the ‘alpha’ state of the manuscript. Still, there are plenty of ways in which we might (in time) be able to reconstruct the original page order (multispectral scans, Raman spectroscopy, thickness mapping the vellum edges, DNA testing the vellum (!), etc). But as none of that is likely to happen anytime soon, all we can do is try not to base our arguments on the present colouring, order, orientation, grouping, foliation or quire numbering of any given pages, unless we have very specific reasons to believe they happen to be correct.

Currently, the only examples I know of likely original page adjacencies are:

- Faint ink / paint contact transfers from f2v to f3r appear to be original (see “The Curse of the Voynich”, pp. 65-67)

- Vellum flaws (see “The Curse of the Voynich”, pp. 53-56) suggest that f9-f10, f10-f15, f35-f36, and f37-f38 were originally neighbouring pages, and may well have all been a single quire in the order f35-f36-f9-f10-(centre)-f15-f16-f37-f38, possibly with the f28-f29 bifolio wrapped around them.

- The reconstructed order of Q9 and Q10 (see “The Curse of the Voynich”, pp. 57-61)

- The order of the zodiac pages, can only (from the way they have been bound) start from Pisces

- I argue (see “The Curse of the Voynich”, pp. 62-65) that the original page order for Q13 (the “water” section) was very probably f76-f77-f79-f84-f78-(centre)-f81-f75-f80-f82-f83.

- From the doodles and unreadable letters on the final page, I think there is good reason to believe that f116v was also the final page of the manuscript as it was originally laid out.

As far as quire grouping in general goes, I suspect that the Herbal pages Prescott Currier described as “Hand 2” originally were arranged in two separate quires (see “The Curse of the Voynich”, pp. 69-70), which I named “Quire F” (containing the current Q8), and “Quire E” (holding the other six “Hand 1” bifolios). But unfortunately this currently isn’t really a lot of help – sorry, I did try my best.

(9) How Can We Untie This Knot?

Basically, we would like to break down the writing into groups so that we can work out in what order the pages were originally intended to appear. Yet while the colour of the ink does vary through the manuscript (implying both multiple sessions and multiple sources of ink), the RGB scans we currently have are not really sufficient to separate them out.

The straightforward solution would be to carry out a calibrated multispectral scan of the manuscript, which should yield plenty of information to track and match inks and paints (and possibly even individual pieces of vellum). As long as we ensure that the range of wavelengths chosen produces useful information, this approach should open up an entirely new angle on the main page-ordering issue, as well as on corrections, emendations and other subtle codicological layering issues.

However: back in early 2006, when I asked the Beinecke’s curators for permission to do even a limited multispectral scan, they turned down my proposals. Perhaps they will change their minds some time soon (after all, “no” only ever means “no today”), but anybody wishing to propose this kind of thing should bear this in mind. Don’t get me wrong, the Beinecke’s RGB scans have been a tremendous asset – it is just that the next stage of physical inquiry now beckons.

A Raman spectroscopic investigation would enable a very different type of art historical analysis: finding out what type of physical materials were used for the very many distinctive individual paints would be a fascinating study in itself (albeit one probably revolving more around 16th century paint composition). However, it is worth noting the difficulties in interpretation thrown up by the Raman analysis of the Vinland Map (another famous Beinecke holding), as this will doubtless colour the curators’ decision here.

A microscopic analysis of the vellum (if it could be done in situ) might, as Glen Claston has suggested, reveal pollen particles trapped inside the vellum. This is another type of analysis to consider: and there may also be enough information present at the microscopic scale to help identify individual hides.

One other analytical approach would be to use a non-contact micrometer to draw up a precise thickness map along the edges of the herbal pages, and from that write some clever software to predict how the original sheets of vellum were folded and cut into quires (these values can be matched with the length of the pages and the shape of each bifolio). OK, it’s not very glamorous: but it’s a simple non-invasive approach which (I think) the Beinecke would be comfortable with (if they think you are sufficiently credible).

(Really, I think any of the above would be the basis of a good student project – please email me if you would like advice about structuring or presenting any proposal to the Beinecke along these general lines.)