For a decade, I’ve wondered whether any of the Voynich Manuscript’s circular drawings depict astronomical instruments – for before satnav there was celnav (“celestial navigation”). Here’s a brief guide to three key instrument types from the VMs’ timeframe, and my current thoughts on the enigmatic circular diagram on f57v…

* * * * * * *

A key navigational problem of the 15th century was determining your latitude. Though many different instruments (such as the quadrant, the cross staff, and the back staff) came to be used to do this around this time, I’m restricting my observations here to the three purely circular ones – the astrolabe, the mariner’s astrolabe, and the nocturnal.

(1) Though astrolabes were originally used for determining the positions of planets and stars, people realised that they could also be used for telling the time (if you knew your latitude), or for working out your latitude (if you knew what time of day it was). Astrolabes were constructed from a complex (but well-known and well-documented) set of multilayered rotating components:-

- A backplate (the mater) whose edge (the limb) is marked round with 24 hours or 360 degrees

- A large circular central recess (the matrix, or womb) in the mater, into which you insert…

- A disk (the tympan) containing a stereographically projected map of the sky for a particular latitude

- On top of the tympan goes a rotating spidery net-like thing (the rete) containing easily recognizable stars;

- On top of the rete goes a long rotating rule (the rule)

- On the back goes a second rotating rule-like thing with two sighting holes / marks (the alidade)

If you haven’t seen an astrolabe dissected, there’s a nice annotated diagram on the Whipple Museum website.

My understanding is that most medieval European astrolabes were inaccurate because they were made of wood, though this improved when they started to be made of metal (an innovation which I understand mainly began in the 15th century). Yet even with well made astrolabes to hand, using them can be a bit tricky, particularly when you are at sea: and they’re not very convenient to use at night either.

(2) So, step forward the mariner’s astrolabe (or sea astrolabe or ring). Though this was little more than a cut-down version of the astrolabe, its key design feature was that it was built to be particularly heavy (and so was much more stable at sea). In contrast to the thousands of astrolabes out there, only 21 mariner’s astrolabes are known: the earliest description of one is from 1551, while historians suspect they came into use in the late 15th century.

Really, this was little more than a superheavy astrolabe limb hanging from a ring and with an alidade on the front: but it did the job, so all credit to its inventor… whoever that may be. The Wikipedia mariner’s astrolabe page notes that it might possibly have been Martin Behaim (1459-1507), but because it seems he was adept at relabeling other people’s discoveries and inventions as his own, probably the most we can pragmatically say is that the idea for the mariner’s astrolabe was ‘in the air’ in the mid-to-late 15th century.

(3) Solving the astrolabe’s other major shortcoming, the nocturnal (or nocturlabe, nocturlabium, or horologium noctis) was specifically designed to be used at night. A 2003 paper notes that the first evidence of nocturlabes was not a textual mention in 1524 (as was long thought), but rather a series of actual devices made by Falcono of Bergamo and dating from 1504 to 1507 (who also made astrolabes, such as this one from the British Museum). For a nice picture, the National Maritime Museum has a 17th century nocturnal here (D9091).

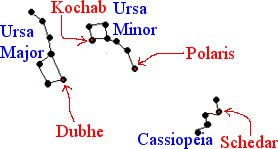

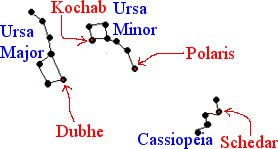

As far as construction goes, a nocturnal consisted of: a rotating outer ring marked both with the months of the year and with the 24-hour time; a hole in the middle of the central pivot that you could see through; and a second rotating ring with one, two, or three pointers. Once you had rotated the outer ring to closely match that day’s date, you would hold your nocturnal at arm’s length, line Polaris up through the central hole, and then align the second rotating ring so that its pointers pointed at some well-known stars (normally Shedar [α Cassiopeia], Dubhe [α Ursa Major], and Kochab [ß Ursa Minor]): there’s some nice discussion here on why these were chosen.) Once you had done all that, you would find (as if by high-tech magic) that the major pointer on the second ring would be pointing to the current time of day marked on the first ring. (Well… pretty much, anyway.)

Here’s a simplified look at the night sky, highlighting the four key stars referred to on a typical nocturnal:-

Incidentally, an open history of science question is whether Columbus had a nocturnal on his well-equipped voyages of discovery. This well-informed page seems to imply that he did, and that it was used to determine midnight – the ship’s boy would then turn over an “ampoleta” (a little sand-glass that would take half-an-hour to empty) to start counting out the daily cycle of shifts. Unfortunately, it turns out that Columbus didn’t properly understand how to use his various astronomical instruments, and that he faked a number of his latitude records. Oh well!

To summarize: though the astrolabe had been used and developed since antiquity, there was little about it that was secret circa 1450. However, this was the moment in history when people were starting to apply their formidably Burckhardtian Renaissance ingenuity to get around the limitations of the traditional astrolabe, by adapting the basic design for use at sea and at night. Yet for both the mariner’s astrolabe and the nocturnal, the documentary evidence is silent on who made them first.

* * * * * * *

What, then, of the Voynich Manuscript?

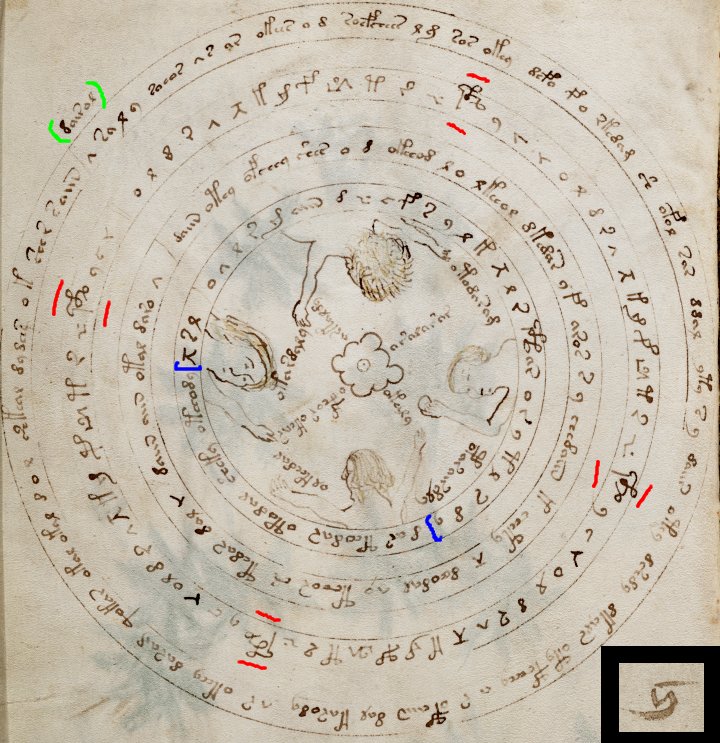

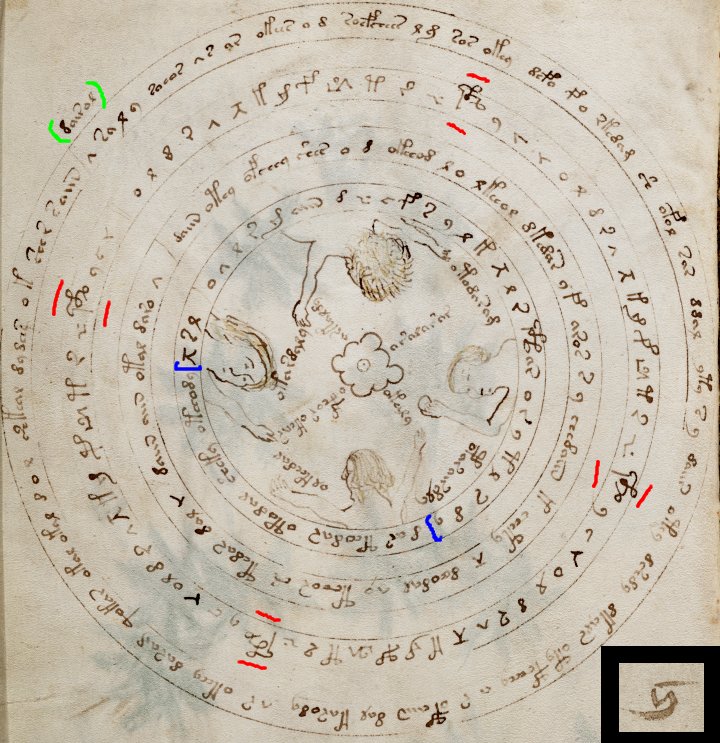

I have been trying to get under the skin of the ringed diagram on f57v for many years: even by the VMs’ consistently high level of (well) anomalousness, this page has numerous anomalies on display that seem to promise a way in for the determined Voynich researcher:-

- Its drawings most closely matches the circular astronomical drawings in Q9 (‘Quire #9‘), yet its bifolio is bound in the middle of the herbal Q8

- It has a curious piece of marginalia at the bottom right

- There’s a spare ‘overflow’ word at the top left [marked green below]

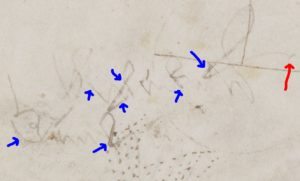

- The second ring comprises essentially the same 17-character sequence repeated four times

- Each 17-character sequence contains an over-ornate anomalous “gallows” character [marked red below]

- The 17-character sequence contains a number of low-instance-count letter-shapes

- The fourth ring contains another long sequence of single characters [marked blue below]

- It has four strange ‘personifications’ drawn around its centre (seasons? winds? directional spirits?)

- It is far from clear what the four personifications are depicting, let alone representing

- Finally, it has a ‘sol’-like dotted sun at the centre

I therefore think that any proper account of f57v should therefore not only offer a high-level explanation of its intent and content, but also a low-level explanation of these anomalous features. The problem is that any reasoning chain to cover this much ground will almost inevitably require a mix of codicology, palaeography, history, astronomy, and historical cryptography… so bear with me while I build this up one step at a time.

First up is codicology: Glen Claston and I agree that f57v was probably the very first page of the astronomical section Q9 – by this, we mean that the two bifolios currently forming Q8 have ended up bound upside-down. So, even though the current folio order is f57-f58-(missing pages)-f65-f66, the original folio order ran f65-f66-(missing)-f57-f58. The page immediately preceding f57v (i.e. f57r) has a herbal picture on it, which is why Glen and I are pretty sure that f57v formed the first page of the astronomical section: while both sides of f58 have starred paragraphs (and no herbal drawings), which also makes it seem misplaced in the herbal section.

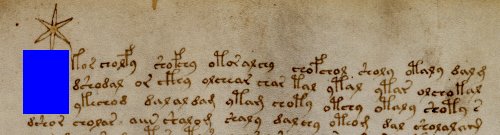

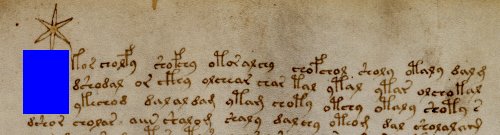

A second clue that this is the case is the marginalia mark at the bottom: I think this is a scrawly “ij” with a bar above it (i.e. secundum), indicating the start of Book II (i.e. where Book I would have been the herbal) – this probably isn’t a quire mark because it doesn’t appear on the end folio of a quire. And a third clue is that the page we believe originally facing f57v (i.e. f58r) has an inserted blank block at the start of the first paragraph, which I suspect is a lacuna [highlighted blue below] deliberately left empty to remind the encipherer that the unenciphered version of this page began with an ornamented capital.

As for the odd word at the top left, the odds are that this is no more than an overflow from the outermost text ring: a similar overflow word appears in one of the necromantic magic circles famously described by Richard Kieckhefer as I described in “The Curse” (though of course this doesn’t prove that this page depicts a magic circle).

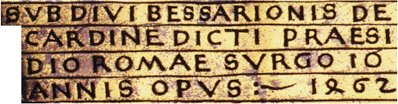

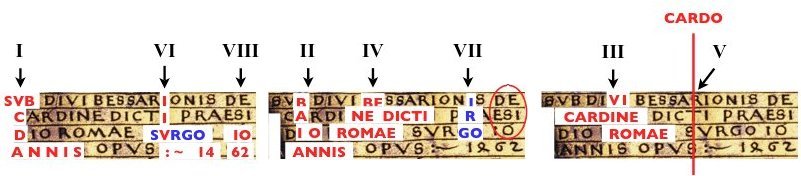

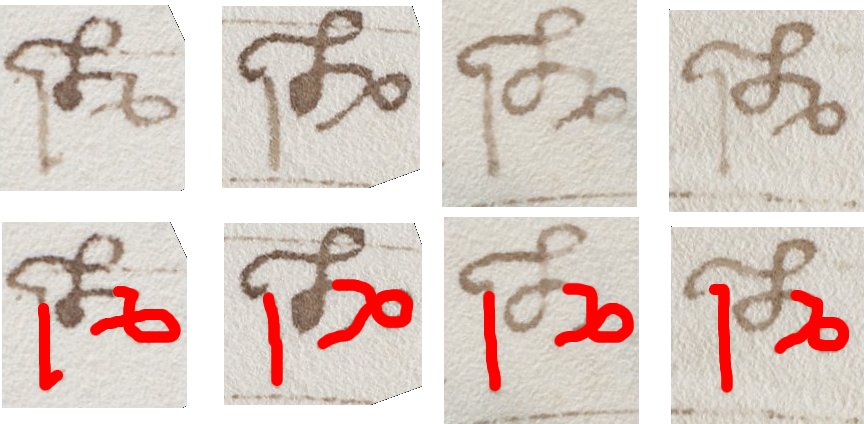

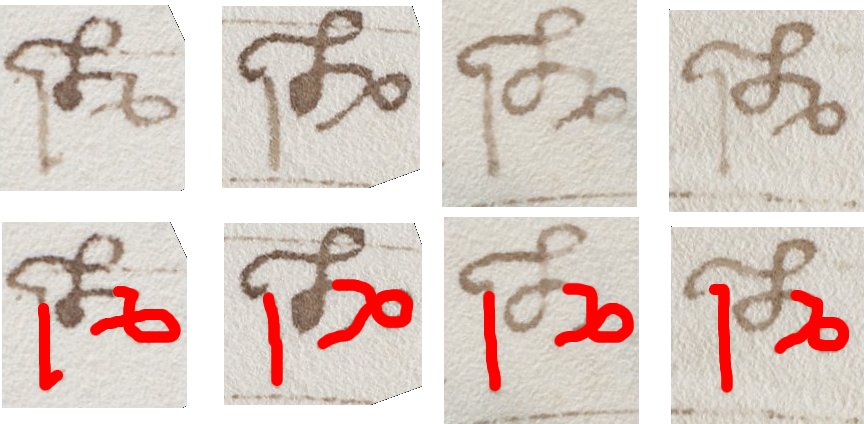

I think codicology can also help us to understand the mysterious 17-glyph repeating sequence, a pattern that has inspired many a high-concept numerological riff over the years: for if you look carefully at the four over-ornate gallows, you might notice something a bit unexpected…

Even though I’d prefer to be making this judgment on the basis of better scans (which seem unlikely to be arriving any time soon, unfortunately), I’m pretty sure that what we’re seeing here is a pair of characters which have been joined together to resemble a non-existent gallows. I’d even go so far as to say that I think that the decision to make this change was probably made while the author was still writing the page: from which I infer that 18 x 4 would have been too obvious, but 17 x 4 was obscure.

If you accept that this is right, then this changes the number patterns completely, because whereas 4 x 17 = 68 doesn’t really have much numerical (as opposed to numerological) significance, 4 x 18 = 72 does – for you see, 72 x 5° = 360°. And if we are looking at some kind of 360° division of the circle, then all of a sudden this page becomes a strong candidate for being some kind of enciphered or steganographically concealed astronomical instrument, because division into 360° has been a conceptual cornerstone of Western astronomical computing for millennia.

For several years, I therefore wondered if f57v might be depicting an astrolabe: but I have to say that the comparison never really gained any traction, however hard I tried. However… the question now comes round as to whether f57v’s circular drawing might instead depict a mariner’s astrolabe or a nocturnal.

That this might be a mariner’s astrolabe is perfectly plausible. The ‘overflow word’ might denote a ring, the second 360° ring could be the scale round the edge, and the four people in the middle could simply be decorative “fillers” for the four holes normally placed in the middle.

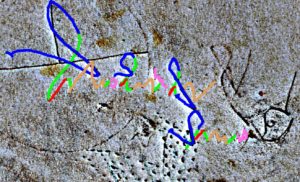

Comparing f57v with a nocturnal, however, is particularly interesting. The obvious thing to hide in the central design would be depictions or denotations of the constellations and the sighting stars so crucial to the operations. Given that there are plenty of different strength lines and curious shapes in the four characters to be found there, let’s take a closer look…

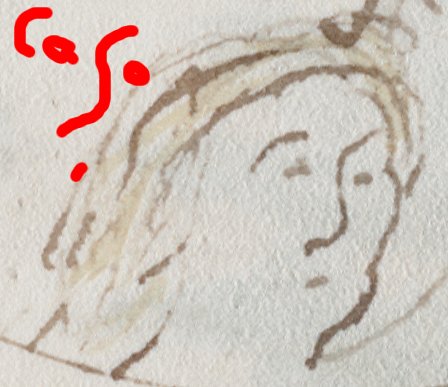

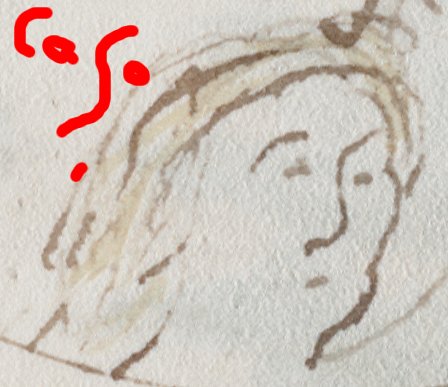

Now, the four elements we’d expect to see in a description of a nocturnal are Cassiopeia, Ursa Major, Ursa, Minor and Polaris: and I suspect that this is what we have here. Look again at the woman’s face on the left, and I wonder whether her name has been quite literally written across her face:-

As for the top and bottom characters here on this page, they have long puzzled Voynich researchers – why are they so wildly hairy and apparently facing away? What kind of a person is being shown here? Perhaps the answer is simply that these represent not people but bears, specifically the Great Bear (Ursa Major) at the top and the Smaller Bear (Ursa Minor) at the bottom.

The final character of the four would represent Polaris (short for stella polaris), which in the 16th Century (?) came to be called ‘Cynosura’ (the Greek mountain nymph who nursed Zeus in Crete). I have to say that I don’t really know what is going on here – perhaps other people better versed in astronomical history or mythology might be able to tell me why this person should be carrying a ring or an egg (?), and what the character’s curious strong lines (nose and top of upper arm) might be denoting.

Yet perhaps the biggest clincher of all, though, is the ‘sol’-like shape right at the centre of f57v. We might be able to discount the possibility that this represents the astrologers’ glyph for the sun, because this only came into use around 1480 (as I recall). For in the context of a drawing of a circular astronomical instrument, is this not – almost unmistakeably – a depiction of Polaris (the dot) as viewed through a hole in the pivot (the circle)?

As always, the evidence is far from complete so you’ll have to make up your own mind on this. But it’s an interesting chain of reasoning, hmmm?

Spookily, the kind of analogue computing embedded in nocturnals has a thoroughly modern equivalent. Polaris does not sit precisely on the Earth’s pole but rather rotates around it very slightly, and so requires a correction in order to be used as a reference for true North (on a ship, say). Hence a spreadsheet can be constructed to make this fine adjustment – essentially, this is a nocturnal simplified and adapted to yield the north correction required. Some good ideas can remain useful for hundreds of years!