Perhaps you well-informed people already knew, but recently I was surprised to discover that during WWII, these three luminary SF writers all worked at the Naval Aviation Experimental Station in Philadelphia. Because this overlaps some of the other history I’ve been working my way through of late, I thought I’d tell this story again (but from my own angle).

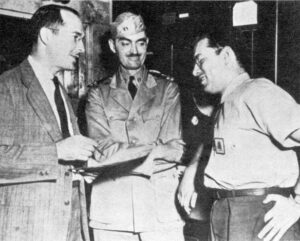

(Image from Asimov’s 1979 autobiography “In Memory Less Green”)

“Astounding Science Fiction”

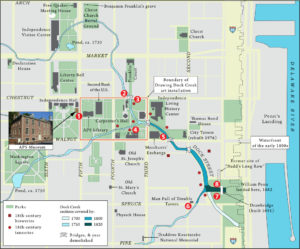

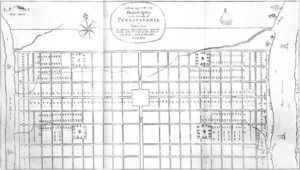

When the United States joined WWII in 1941, Robert Heinlein (who had previously served in the US Navy, but had been discharged in 1934 because of ill-health following tuberculosis) immediately asked to be re-enlisted. Though he was (eventually) turned down (because of poor eyesight), he was then asked (by Commander A. B. Scoles, his old classmate and fellow Naval Academy graduate) to write an article for Astounding magazine about the Aeronautical Materials Laboratory at the Naval Aircraft Factory in Philadelphia (that Scoles ran). When Scoles also asked if he would like to work there, Heinlein agreed. As an aside, one of his superior officers there was Virginia Doris Gerstenfeld, who Heinlein later married (after his second divorce in 1947).

While working as a civilian employee (his military clearance took a while to come through), he recommended they hire his fellow writer L. Sprague de Camp, who had a similar background in engineering. As with Heinlein, Sprague de Camp then encountered a delay before he could attend a suitable course at the Naval Training School at Dartmouth. Hence he also initially worked as a civilian engineer there before completing his course and gaining a commission as a full Lieutenant (much to his surprise, because he had only expected to become a Lt J-G).

Heinlein’s other personal personnel recommendation to the factory was Isaac Asimov, who had a Master’s in chemistry. Yet again, it took six weeks for Asimov to get clearance, his “first experience with government red tape”. This was his first time he had lived away from his family, and quickly discovered that he “wished to live soberly and reasonably – exactly as my parents had expected me to live. It was a dreadful disappointment.” Asimov subsequently thought of his time working there as a failure – that if he had been employed to do the same work during peacetime, he would have been fired. And so he returned to writing in 1943.

All the same, that’s how come the three (now very famous) SF writers all ended up working in the same Navy Yard during WWII – not exactly coincidental, but an interesting historical adjacency nonetheless.

What did they each work on?

This is actually the part I’m most interested in, because their memories of what they did there all help cast a bit of light on the innermost workings of the US Navy’s generally secretive R&D.

According to this page, Heinlein supervised a pressure chamber for testing the high-altitude suits (e.g. for stratospheric ballooning) that would later become space suits. In a 1986 foreword he wrote for Theodore Sturgeon’s novel “Godbody”, Heinlein heavy-handedly hinted at his top secret work there, including an (unnamed) radar project plus a brainstorming job on “antikamikaze measures” for “OpNav-23” (whatever that was). Though for balance, I should add that many of the Heinlein biographical sites I’ve looked at are more than a little skeptical that he actually did much top secret stuff at all.

Similarly, de Camp ran a separate engineering section, which “perform[ed] tests on parts, materials and accessories for naval aircraft; and when called upon, to do original design and development work.” Part of his worked involved running a “Cold Room” for low-temperature equipment tests. This is described in his 1996 autobiography “Time and Chance” (available for £1.99 on the Kindle). [Did you know de Camp’s first name was “Lyon”?] The contractor’s freon cooling circuit never worked, so in the end they used dry ice cubes to brute-force the Cold Room to -96F. De Camp also worked on “trim-tab controls, windshield de-icers, oxygen regulators, low-temperature protective equipment, hydraulic valves, corrosion controls, and piezoelectric materials“. Though I should add that he poured scorn on a story about ‘three pulp writers designing a space suit’ that appeared in print: “the nearest any of us got to space suits was when I saw a suit, designed by a private contractor, being tested by Larry Meakin, one of the civilian engineers, in the Altitude Chamber“. The last noteworthy thing de Camp did while at the Naval Air Experimental Station was “to put on an Exhibition Day, with flying demonstrations“, as a piece of general public outreach. However, his memoirs give no further details of what that involved.

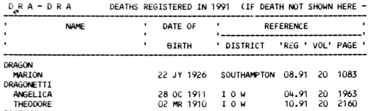

Asimov’s memories in his 1979 autobiography “In Memory Yet Green“ appear in Chapter IV “The War and the Army – in That Order“. His work at the Philadelphia Navy Yard rarely took him out the chemistry laboratory: “its purpose […] was to maintain the quality and performance of hundreds of different materials used by the naval air forces“. His work “consisted largely of testing different products intended for use on naval aircraft – soaps, cleaners, seam sealers, everything – according to specifications. […] I was testing various plastics and other substances for waterproofness by placing weighed amounts of water-absorbing calcium chloride in aluminum pans, covering them with the film to be tested, and sealing those films with wax around the edges. I then weighed them, placed them in a humidifer for twenty-four hours, took them out, dried them and weighed them again.” I don’t know about you, but that sounds like a scream.

Finally, “The Philadelphia Experiment”

L. Sprague de Camp was once asked by a fan about “The Philadelphia Experiment”, as described by Berlitz and Moore in their 1979 book. “Aha!“, said the fan, “Now I know what you, Heinlein and Asimov were up to in that Naval laboratory” – i.e. popping the destroyer escort USS Eldridge and its crew through some kind of crazy dimensional portal to the Norfolk Navy Yard (which was 200 miles away), and then popping it back again.

Of course, de Camp thought the entire thing was complete nonsense (“a book of marvels for the gullible”) that none of the three writers had even heard of during their time there. Having said that, he did concede that “an invisibility project would have been more fun than running endless tests on hydraulic valves“. I’m sure Asimov, at least, would have agreed.