This week is “Shakespeare Week” at my son’s school: his year have been allocated A Midsummer Night’s Dream, and so get to do their lessons in costume for a day. All of which yielded an ideal family opportunity to break out one of those tediously aspirational The-Bard-For-Kidz boxed sets and run through a heavily abridged version with him to see which character he’d like to play (i.e. which outfit we’d be rapidly constructing). And so Puck it was. 🙂

In business school terms, Oberon and Puck come across to me as an idealized (i.e. pragmatic yet dysfunctional) CEO and CTO pair, i.e. where Puck trolls around the wood trying to implement Oberon’s barking mad strategies. Specifically, Puck drops a tincture of “Love In Idleness” into the eyes of those asleep, confident in the knowledge that they will fall in love with the first person (or indeed donkey) they see when they wake up. With hilarious (and/or dramatic) consequences, etc.

Shakespeare is full of folksy herbal stuff like this: in fact, you don’t have to look very far these days to find academics who argue that the witches in Macbeth were talking about not literally about “eye of newt”, “toe of frog”, and “wool of bat”, but referentially to ‘eye’ plants (such as daisies!), buttercups, and holly leaves respectively, as a humorously winking aside to the audience. If correct, this pitches the witches closer to pantomime dames (such as Nana Knickerbocker, my son’s favourite) than to Cruella De Vil… but I digress!

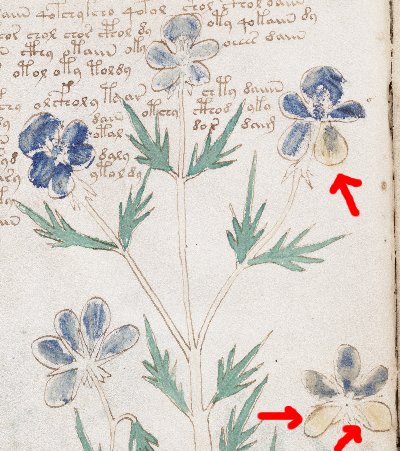

Anyway, it turns out that ‘Love In Idleness’ is actually viola tricolor, the purple wild pansy (from which modern pansies were cultivated in the 19th century), A.K.A. ‘heartsease’ and hundreds of other names. Which, of course, is the cue for a picture of the plant on Voynich Manuscript page f9v, for which numerous people have suggested viola tricolor as a good match:-

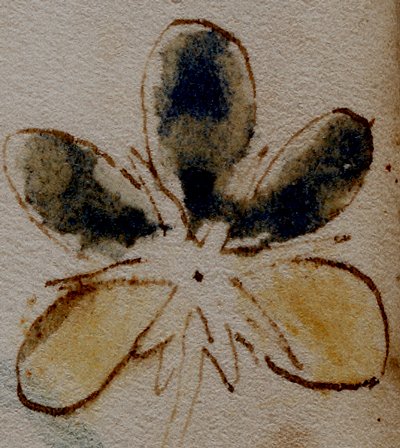

As normal, the unsympathetically-applied blue paint looks as though it was added by a later owner’s young child: yet what is strange here is why three of the leaves seems to have had yellow paint added instead (which is what my annoying red arrows are pointing at). If you contrast-enhance the bottom-right flower, you can see this quite clearly:-

Why was this so? I don’t know, but perhaps that’s not a bad question to be asking. Is that enough random digressions for one day? Probably! 🙂