A month ago, I exchanged a series of emails with a nice – though somewhat retiring – correspondent, who suggested that I might consider whether the Somerton Man was in fact Charles Gazzam Hurd. Here’s Hurd and his son (Charles Gazzam Hurd Jr):

The Disappeared

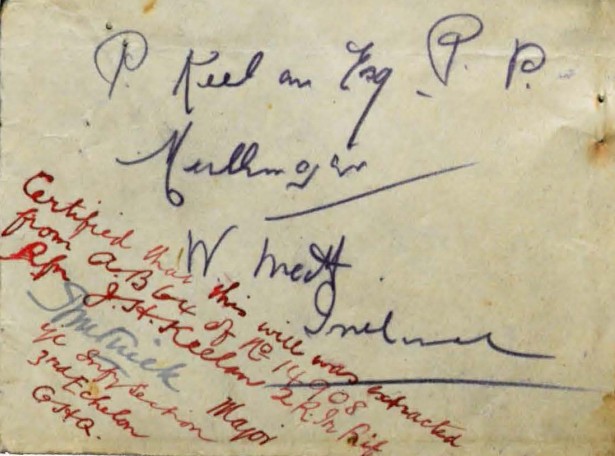

The last we know of Hurd’s life (from The Doe Network) is as follows:

- On 18th Feb 1937, Hurd left his workplace at 15 William Street, Manhattan (he was a manager of a real estate and mortgage department) at a normal time

- He had dinner at a restaurant / night club on East 54th Street

- He cashed a small cheque and left

- He crashed his Ford convertible coupe “into a pillar of an elevated railway structure at 3rd Avenue and 37th Street”

- He (apparently) suffered only minor injuries, drove off but then disappeared forever

At the time this happened, he was separated from his (wealthy) wife Marie Louise Schrieber, and was living at the Kenmore Hall Hotel on 23rd Street and Lexington Avenue. She remarried within a year of Hurd’s death.

His son Charles Gazzam Hurd Jr (born 1930, died 2015) seems to have been a thoroughly lovely bloke: “one time he orchestrated an epic Halloween prank involving a séance, the ghost of Benedict Arnold, and a couple of hydrocarbon fireballs that sent several 11-year-old girls into hysterics; an event that surely would have sparked an outcry on social media today.” Rock’n’roll!

Also: Hurd’s granddaughter Amy Hurd Fetchko has been doing a lot of her own digging, and there’s a nice podcast interview with her that covers much of what she has found, triggered by her father writing his memoirs. Did CGH Jr – as he believed he remembered – watch Tarzan with his father four months after his father’s death? Or had his father committed suicide in despair (as part of her family believes)? All very mysterious.

The Theories

It’s not widely known that there’s an (actually fairly sizeable) Internet community of people who try to identify John & Jane Does, often by connecting the few facts associated with a given person (height, build, hair colour, clothing, age) with those of other individuals who have disappeared. Indeed, a few of the more successful instances have ‘broken out’ into mass media (articles, books, TV, and probably even films).

On Reddit’s r/UnresolvedMysteries, plenty of people weigh in (a) that Hurd was probably a drunk driver, and (b) given that the East River was a mere three blocks away from where he was last, therefore (c) the most likely place you’ll find both him and his car (which disappeared at the same time) is the bottom of the river. Drunk driving, depression, head injury, concussion, impulsive suicide… all these are possible and in play (not at all unreasonably, it has to be said). (Websleuths don’t hugely disagree with this.)

Amy Hurd Fetchko also suggests that her grandfather – who she says was definitely a gambler – might possibly have got into money trouble with the Mob, and as a result either got killed or just changed his name and started afresh somewhere else. (She wonders whether the restaurant / night club where he had eaten might have been a Mob joint, etc.)

Alternatively, you won’t have far to look in the broader group of (what one might call) ‘The Disappeared‘ to find middle-aged men who dropped out of their life to start a new life with a second (often bigamous) wife. So it’s not entirely surprising to find that a number of amateur investigators have proposed that Hurd might have – by some random path – have ended up dead on Somerton Beach on 1948, i.e. that he might have started afresh in Australia but ended up as the Somerton Man.

A good source on this theory is a set of (nine) pages on Unexplained Mysteries. As you’d expect, it all pivots on ear shapes and so on. But… all the same, it just feels wrong to me. Dredge the East River, save us all the hassle, OK?

(Now The Real Post Begins)

OK, even though I’ve assembled all the information on Charles Gazzam Hurd in one place above, the stuff that actually interests me here isn’t Hurd himself, but rather the swirl of stuff around ‘The Disappeared’. For me, a much better question would be about why so many people are interested in identifying John / Jane Does.

Is this about closure, doing good, being helpful, connecting to (often long dead) people in a disconnected modern world? Is it about becoming interested in something, and then repeatedly scratching some kind of previously-unnoticed research itch that never quite scabs over? Is it about just finding an online community that you can settle into, safe in the knowledge that there really aren’t any terribly bad theories? Or is it about being nosy, opinionated, mouthing off, bickering, forum fighting, disagreeing, and occasionally trolling relatives and descendants?

Or some wobbly mix of all four?

Regardless, one thing that unites almost all of these cold cases is that there is very rarely any money to be made. Unlike the Zodiac Killer (where just about everybody involved seems to have written one or more awful books, along with a fair few of the fake letters trolling the police in the 1970s), there’s no huge glory to be had in identifying nameless victims. So in many ways, ‘Doe-hunting’ is – on the face of it – a fairly harmless pursuit.

For those who try to do this in a sensible way – i.e. by going to archives and primary sources where possible, and taking a resolutely evidence-centred approach – there’s nothing much you could say is wrong with what they’re doing. What happened happened, and nothing you can do now can unhappen it, right? It’s just trying to help, right?

Sort of, yes: but also sort of no. While it’s certainly nice to help identify people who have died mysteriously without a trace, people have no alienable Human Right to be Identified in the Unlikely Event of Their Mysterious Death. And given that these searches tend to be very long-term, they consume a lot of the searcher’s life, often yielding little or nothing of significant value in return. So, putting all the “The Journey is the Destination” blather to one side, there is a personal cost to the living to be considered here: the John / Jane Doe themselves have nothing much to benefit either – after all, it’s a bit late for closure for them.

And before you channel your inner Moe and say “Think of the family! Think of the family!“: in many, many cases the family simply have no idea at all. Someone just lost touch, and for countless years they stayed lost… until the Online Cold Case Enthusiasts gleefully poked their Internet noses in, typically offering a decades-later hallucinogenic mix of sort-of-hope and victim details gleaned from scratchy old police reports.

In my opinion, the real reason people get involved tends to be something quite different: typically (I suspect) more to do with finding kinship in an online community than with an overdeveloped sense of morality or desire for natural justice. Finding Charles Gazzam Hurd’s family tree more interesting than your own family tree is all very well, but a dispassionate observer probably couldn’t help but wonder whether this does sort of hint at an awkward modern dissociation from your own basic reality, hmmm?

Blame Davina & Co? Why not!

This is also a pastime that familial DNA is rapidly transforming, making it just about as redundant as redundant can be. Why trawl through thousands of pages of scrawly old archives for years (or even decades) for a half-glimpse at something that may or may not be connected, when GEDmatch can move you closer to a rock solid answer inside a day?

Maybe it’s wrong to blame Davina and her TV buddies for making this so gosh-darn visible. All the same, it’s hard not to look at both the serried ranks of DNA-themed documentaries – national treasures (Piss-)Ant & Dec, dahlin’ Stacey Dooley, Bloodline Detectives, etc etc – and the rise in interest in DNA police cold-casery and see some kind of correlation there, right?

And as more and more people upload their DNA to databases, there seems little doubt in my mind not only that database results will become more and supportive, but also that the ever-improving familial-searching tools wrapped around them will automate more and more of the research processes involved.

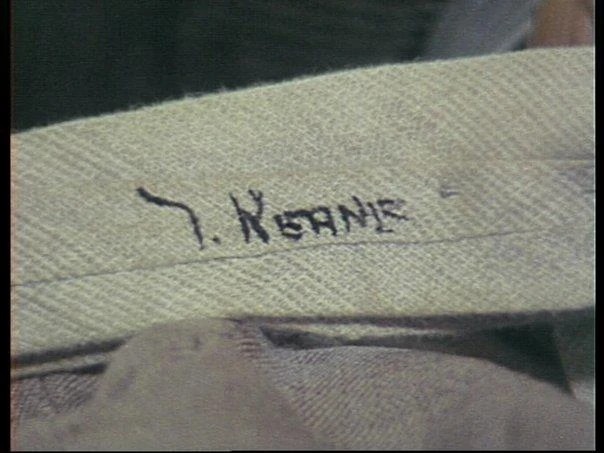

At the same time, my understanding is that we’re simultaneously about to be hit by a rapid influx of AI-powered tools able to read old handwritten documents. Hence it seems highly likely to me that it won’t be too long before we see companies making this accessible at scale, where their “Google for genealogy”-style offerings pull together and automate a lot of the genealogical grunt work. (And let’s face it, most online family trees you’re likely to see are full of over-optimistic junk unsupported by any genuine evidence. So there’s a great deal to improve on here.)

So, even though we’re just about at the point where a load of researchers are getting actually quite good at genealogy and cold case research, we might also be at the start of a period where all that stuff becomes heavily automated and commoditised. And what then of online cold case forums? Computer says yes, computer says no: but either way, the computer says it.

Looking ahead, then, I expect DNA tools will obliterate not just individual cold cases but in time also the whole idea of cold cases. Similarly, I expect AI will obliterate genealogy (and why on earth haven’t LDS tried this, you’d have thought they’d be at the front of the queue?). I give it 10-15 years before they’re both as passé as wax cylinder recordings.

What Then of Cipher Mysteries?

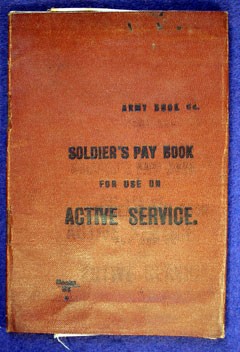

So what then about the Somerton Man, and the Adirondack Enigma, and so forth? Yes, where cipher mysteries form just one strand of any cold case that is more of a WhoWasIt than a WhoDunnIt, I indeed think it’s a pretty safe bet that the plucky DNA genealogists will (eventually) get on board and figure out the person’s real identity.

In the case of the Zodiac Killer, police cold case teams (and the swarm of TV documentary teams kissing their poh-lice butts) must now surely be slowly grinding their way through the mass of Zodiac envelopes, stamps and other evidential gubbins looking for DNA hits. At the very least, you’d have thought – as I’m told happened not so long ago with the Cheri Jo Bates cold case – they’d have figured out which nutters sent taunting letters to the LAPD (hint: most of these probably weren’t sent by Zodiac). To be honest, it wouldn’t surprise me if 75% of those were actually sent by idiot Zodiacologists, but that’s perhaps going to be an unpopular opinion for a while yet.

However, the one thing that we’re still a loooong way from is using technology to crack top-end cipher mysteries. For example, while Hauer and Kondrak’s 2021 paper (on the Dorabella Cipher) accepted that Keith Massey’s observations were extremely strong, the authors still just waltzed past them regardless, despite their obvious inconsistency with, say, everything that they had hypothesized, written, and concluded. All of which made what would have otherwise been a basically good paper end up a bit too ‘baity’ for my taste.

So there you have the actual start of the art: known-system ciphers we can now crack in no time, but cipher mysteries? There’s no sea turtle that can hold its breath long enough for cipher mysteries to reveal their secrets. But in the end, perhaps that’s a good thing, right? 😉