Online webcomic Sandra And Woo has just taken a detour into CryptoLand, with a Voynich-inspired page called The Book of Woo to celebrate its 500th edition. What’s more, author Oliver Knöerzer (AKA “Kernel River Zoo”) has offered a $250 reward to “the person who is able to provide a decipherment that’s sufficiently close to the plain text“, plus “another $100 to two charities determined by the readers who contributed the most useful information for breaking the code.” Really, Oliver, I’d have helped regardless. 😉

The Book of Woo’s most obvious predecessor would seem to be the Codex Seraphinianus, which is also “primarily a work of art, not a puzzle for the general public“, though I wouldn’t describe the Book of Woo as being quite as hardcore as that (but then again, what is?). The Vick Industries cipher seems to be a more design-oriented mindset entirely, though the art-house rationale behind that has yet to emerge into the light.

How is anyone supposed to decrypt The Book Of Woo? Helpfully, Knöerzer does throw a handful of hints in our path, though mainly about what it isn’t rather than about what it is. He says:-

* The encryption isn’t based on an algorithm only suitable for computers which executes a loop 100 times or something like that.

* The encryption isn’t based on some sort of device or mechanism that is hard to get.

* No “classical” steganographic method was used since that would just be impossibly hard to crack.

* The plain text is some sort of literature, as one can guess from Woo’s comment and the illustrations. A lot of time went into the plain text as well, it’s not just a copy of the first page of Rascal or something like that.

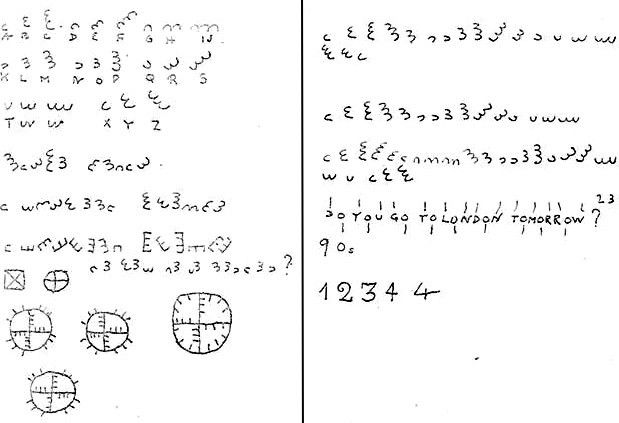

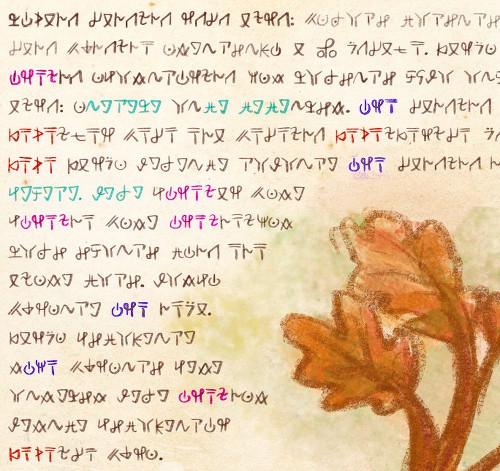

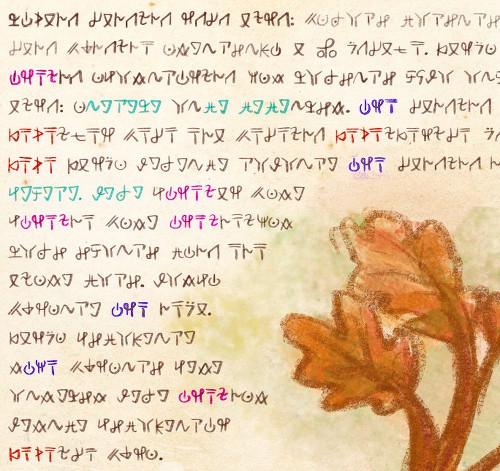

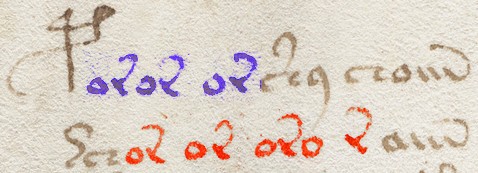

But he also warns that “[if] you think you can simply carry out a frequency analysis on the letters and be able to reconstruct the English or German plain text this way, well, that’s just a waste of time.” Indeed, even a brief look at the text reveals blocks of characters arranged in a very artificial CVCV (consonant-vowel-consonant-vowel) manner. There are also quite a few patterns that are repeated multiple times: here’s a colourized section of the first page, so you can see a bit of what I’m talking about…

What’s going on here? Well… I’ve had a few brief email exchanges with Oliver recently, so have possibly at least a flicker of an idea. And given that he has already openly flagged both the Voynich Manuscript and my book on it (The Curse of the Voynich) as having been useful (he’s even reused the Voynich’s “T” gallows character in his cipher alphabet), it probably wouldn’t hurt to recap a few Voynich-related observations here. 🙂

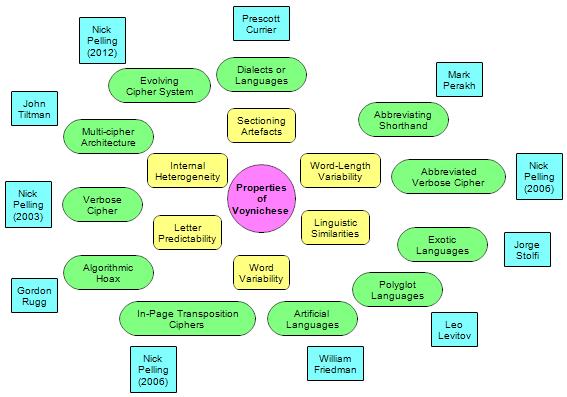

The first thing to say about ‘Voynichese’ (the structure that shapes the Voynich Manuscript’s text) is that there seem to be two main schools of thought: (a) that it’s a cipher system that for some reason our statistical toolkits aren’t able to help us much with, and (b) that it’s a real language but we’re too in love with our analyses to see the bleedin’ obvious.

(For the record, I’m in the (a) camp, which means that when I look at a map of all the different types of Voynichese evidence, I want to understand what kind of trick was used to confound all the different statistical tests, rather than throw my hands up in the air and say “Stats, shmats!”.)

The second thing to note is that almost all of the Voynich Manuscript is written using a very compact alphabet (roughly 22 characters), whereas The Book of Woo uses something like fifty unique shapes (I haven’t transcribed it yet, but that’s how it looks). What connects them is that they are both very predictable at the character level… up to a point. That is, in some circumstances you can reliably predict what the next character along is going to be, but in other circumstances predictions can be of little use.

(For what it’s worth, I believe that it is this specific combination of predictability and unpredictability that convinces people that Voynichese is a language, whereas real languages only tend to work like that in a few very specific ways, e.g. “q” almost always being followed by “u”.)

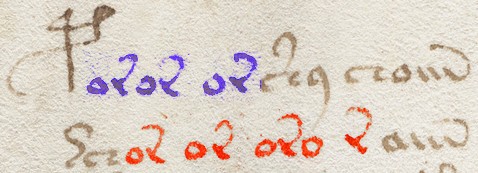

Trying to account for this property ultimately led me to conclude that the Voynich Manuscript in part uses “verbose cipher”, i.e. employing pairs or groups of letters to encipher single letters in a misleading way. For example, the Voynichese letter-pair “or” gets repeated immediately after itself a number of times, with the best known examples being on page f15v:-

Do any real-life languages do this? I don’t think so, but that remains a matter of opinion.

The Voynich Manuscript has a large number of extra curious properties that I believe point to other tricksy mechanisms (e.g. in-page transposition of some sort, if you please), but my suspicion right now (based only on having a nose around it) is that Oliver may have found these unnecessarily abstruse to build a cipher around.

No: I think what’s going on in The Book Of Woo will turn out to be largely based around verbose cipher – specifically a combination of paired letters. Having said that, the big problem with a simple verbose cipher is that it is, well, as verbose as it sounds: and so to make it not bloat as badly as a Microsoft application, it needs some compression tricks to be used at the same time.

In the case of the Voynich Manuscript, I suspect that verbose cipher gets combined with the kind of scribal abbreviation in use during the 15th century. Similarly, because the overall word-length isn’t too extreme for The Book of Woo, I suspect (a) that certain letters used at the start or end of words will encipher prefixes or suffixes, somewhat like a kind of shorthand; and (b) that it’s more likely to be English than German. 😉 It may well also be that certain letter pairs themselves encipher common letter pairs or even letter triples (such as “the”): these are the kinds of tricks I’d expect to see here being used to disguise the structure.

And yet… words seem to be words (i.e. it’s an aristocrat cryptogram rather than a patristocrat cryptogram), so it’s very much as if he wants to help us, not hinder us. So even though it looks a bit tricky at first glance, maybe it will all fall out nicely in the end. We shall see, hopefully before issue #1000! 😉