This is a story about three men, two of them alive and the other long dead: and, as Steve Martin famously said at the start of L.A. Story (1991), “I swear, it’s all true“…

The Somerton Man

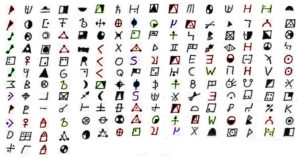

Mysteriously, our first protagonist was found dead on Somerton Beach near Adelaide on 1st December 1948: his identity, despite the passing of several decades since, has still not been determined. Yet it recently turned out [*] that this ‘Somerton Man’ was known by at least one person – a nurse who once signed herself “Jestyn”, but whose real name was Jessica Thomson (neé Harkness), and whose Adelaide phone number was written on the back page of a book later connected to the man, though she never disclosed his identity to anyone (if indeed she ever knew it).

As far as evidence goes, the cold case associated with this man has heaps of (for want of a better word) “micro-clues”: and we really should be able, with all our modern databases, computers, and crowdsourced collaborationware, to identify him without much difficulty. Yet apart from the fact that he was a fit-looking guy not much older than forty with an enlarged spleen, we don’t know (a) who he was; (b) where he was coming from; (c) where he was going to; (d) what he was doing; or even (e) what killed him, let alone anything so fancy as (f) why.

All of which is defensive researcher-speak for we know diddly-squat of importance about him: the truth is we haven’t even got started.

As a result of all this, what can only be termed wretchedly hopeful theories – was he romantically connected with the nurse? was he an American spy? a Soviet spy? a uranium prospector? a car thief? a black marketeer? a Third Officer on a merchant ship? etc etc – hover over his long-dead corpse like flies above dung.

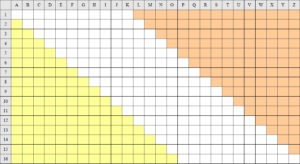

But the thing he now most resembles is a blank Sudoku grid – a puzzle which has at least as many answers as people scatching their heads over it. Why not insert your own pet theory (or indeed theories) into his still-basically-blank grid? Some days it seems as though every other bugger has: welcome to the world of the Somerton Man. 🙂

Derek Abbott

Professor Derek Abbott is our second main protagonist. A few days ago, a long-form piece in the California Sunday Magazine laid out his personal journey from obsessive London schoolboy to Professor of Electrical & Electronic Engineering at the University of Adelaide.

But most importantly, the piece finishes up with something that has been an open secret within the Somerton research community (as if anything so ramshackle and disparate can have so grand a title): that a few years ago Abbott married Rachel Egan, by whom he has three young children. Oh, and if you didn’t already know, Egan’s grandfather was Robin Thomson, the nurse’s son: which certainly directly links Abbott to the mystery of the Somerton Man, and quite possibly to the dead man himself.

Unfortunately, Abbott has devised a whole host of strategies to work around his well-trained stance of scientific impartiality, because he has become utterly convinced that the Somerton Man was Robin Thomson’s real father, despite having (as far as I can see) no proof of this whatsoever beyond really wanting it to be true. And so, over the last few years, Abbott has conjured up all manner of petition-backed legal motions to exhume the Somerton Man (essentially, a techy ‘fishing trip’ to extract DNA from the dead man’s teeth or bones), every one of which has been rejected.

Abbott’s latest variant on this theme – to convince American crowdfunders to back his group’s ongoing research via a £100,000 Indiegogo campaign – currently seems fairly dead in the water (having raised roughly £227 after 18 days, i.e. less than 0.25%), despite his efforts to promote it to gullible open-minded American backers, even floating the possibility of some long-winded family connection between the Somerton Man (or, to be precise, between Robin Thomson who he believes to have been the Somerton Man’s son) and Thomas Jefferson’s family.

For me, the two biggest problems with Abbott’s Indiegogo campaign are (a) that it doesn’t actually specify where the money would go, just that it would be spent on a range of things Abbott believes would best achieve the goal of identifying the Somerton Man, even though he only really has a single theory in play that he wishes to try to prove; and (b) that, given that he plans to put a fair tranche of this Phase 1 cash on building videos and lobbying to promote a putative “Phase 2” (raising even more cash and doing even more complicated tests), he hasn’t exactly been open about this.

Actually, it turns out that crowdfunders are far less gullible and, frankly, far cleverer than Abbott seems to believe them to be. They like proper details on a project page (ones they can actually check for themselves); they like plans that are specific, believable and actionable; and they like to back people who are taking on difficult things that benefit everybody, not just themselves. Abbott clearly believes that he has ticked all of these boxes: I don’t think he has.

Of course, it’s down to individual crowdfunders where they put their money, and Abbott might yet get stumble into a nest of random accidental energy billionnaires who end up throwing a wodge of Monopoly oligarch money in his direction. All I can say is that as far as codes and ciphers go (this is, after all, Cipher Mysteries), all Abbott and his students have managed to do in eight years is essentially what Aussies super-codebreaker Eric Nave did in one day in 1949 (and without computers to help him). Hence I wouldn’t expect them to make any progress with the specifically cipher mystery side of this story any time soon.

Feltus

The California Sunday magazine piece also lays out Abbott’s bitter ongoing rivalry with former South Australian detective Gerry Feltus. Feltus, who retired back in 2004, considers Abbott a pest, and – I’m sure it’s there between the lines somewhere, but please correct me if I’m wrong – an annoying prick with it. Furthermore, though Gerry has never said such a thing to me, I’d be unsurprised if the phrase completion “…and Costello” looms large in his mind whenever he hears the Professor’s surname. Let’s face it, the Aussies really are masters of sledging, so Abbott’s surely bound to come out wet in any pissing contest.

The key difference between these two men’s appraches is plain to see. While Abbott knows exactly what family history he wants to prove and is willing to spend £100K of other people’s money (in Phase 1, and probably double that in the Phase 2 lined up in his mind) to do it, Gerry Feltus is the opposite: patient, meticulous, careful, and seemingly immune to theories. He thrives on the fuzz of doubt: and what he says and writes is all the better for it.

You also don’t have to look very deeply to contrast Abbott’s attempts to embrace the wonders of crowdfunding and Internet self-promotion with Feltus’s dislike for the Internet’s noisy troll-yappery. In many ways, Feltus’ book The Unknown Man is the epitome of doubt, care and patience: the two men may be united by the Somerton Man, but in every other aspect they really are chalk and cheese.

Yet in a way, this kind of starkly opposite pair of trenches isn’t a helpful part of their discourse: in my opinion, pure credulity and pure doubt are both inadequate methodologies for tackling something as historically complex as the Somerton Man.

And so it is for me that even though Abbott often comes across as though he is a scientist doing bad history, Feltus is still thinking too much like a detective, and not enough like an historian – and there’s a big difference.

For sure, Feltus’s overall approach is hugely better than Abbott’s: but – in my opinion – what differentiates the best historians is a driven willingness to choose just the right kind of a limb to go out on to help them find the key evidence they need, and I’m not sure Gerry – who I like, if you hadn’t worked that out by now – has yet developed that ability. (Abbott thinks he has, but he plainly hasn’t.)

The Lessons Of History

Oddly, the cipher mystery world has seen something similar to all this before, insofar as Abbott is trying to raise funding for what constitutes a full-frontal attack on the Somerton Man mystery. Argably the closest parallel is Colonel Fabyan’s Riverbank Labs from a century ago, that famously brought William Friedman and Elizebeth Friedman together. Yet the central point of what Fabyan was doing was to try to prove something that he firmly believed was an a priori truth: that the real genius behind all William Shakespeare’s fine words was none other than Francis Bacon.

Despite the fact that the whole exercise yielded good incidental results (though I would expect that the Friedman’s would have met and perhaps even married through Govermental crypto channels), Fabyan’s attempt to prove Bacon’s authorship was still a foolish thing to be trying to do.

Perhaps Abbott’s efforts will incidentally / accidentally yield secondary long-term benefits: it’s always possible. But it doesn’t mean that I don’t think he’s ultimately doing just as foolish-minded a thing as Fabyan was doing, back a century ago.

[*According to her family in a recent TV documentary*]