Here in the UK, it all started with a story in 27th August 2015’s Daily Telegraph:-

Didac Sánchez, a 22-year-old Spanish IT entrepreneur, says he has deciphered Second World War message following a three-year effort at a cost of €1.5 million (£1.1m) – but won’t reveal its message.

Sánchez claims he told GCHQ of the message’s contents: but GCHQ (of course) denies all knowledge of it.

Now, I have to admit that this is quite a different angle from the media’s usual cipher mystery-related tosh. But what’s in it for Sánchez? Ah, the Telegraph went on to say:

He [Sánchez] now plans to market new security software based on the code, a system he has christened 4YEO (For Your Eyes Only) and which will allow any text, document, WhatsApp, Messenger, SMS or Skype conversation to be encrypted, as well as telephone calls.

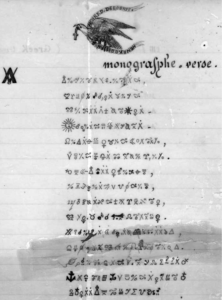

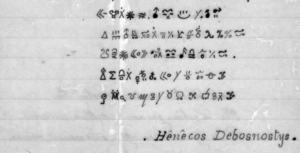

And A Didac Sánchez Cryptogram Too…

And – mirabile dictu – Sánchez’s clever people have posted up a challenge cryptogram supposedly generated using 4YEO’s software, offering a bounty of 25,000 euros to the first person who can crack its “indecipherable” secrets before, errrm, 31st December 2015:

GDNFP IUALI ZOANN EEING DUORL IELTE ROMSO EVCIS AIFON NBNTN IEPSR LAAAT JELAE IMIRN RSNEP IADIA NIATD DPVRO RURLU UAELP RLASR AAOSQ PDSOY EMINL RIDLN NSIEA AEULA AFSTO DIIUF RRRCG EEZIS BAXTI MMORI ORANO FHDER DCNNT NRADA ETAER CDNIO EEAIO EROMT TUDVI AOCDS RHSEU RLALQ CCOCC MIEON NRNIT TOESF OAAMN ANTAO OICEJ TOSBD DEPIR OIANE AOZUE ECCCN IAEIS REECI IRNUR IATCE FSEUC EIENC ROASP COPSU LNUTI VOUES RACCR SYNCA MROIU TLJOB UVSOO JIRLE SSETU TNNOT ASRNE IOBCU NALEU OMEER GINOU AAETL STHER ONLAR ROTIE LENDR AEEYO TRSBR TDRTE HETRR ICUEL TRDCE ASNND TUCOD MDUJA OESPL RESEG OMOCL TAMTI IEGLM AAERR RRSEN SIBAI EICDL RILCE LOXES ELUEO CTANP TNRYU XGGTA NSTIO DSADC CDEER EODNA SAALS CCZEE EENRE LAOOR VASHA SLEAJ CAITE HRTER ELNIA GNTEL DSAAN EOFTD NURAD OSACE MDICR IOACT NEERO OATCA IRPAO NISMD SVECT NLYLT TETNS HSACL NETNL PGIEU EEEDL DCTSR PÑMDM ATUED OOSTS YERCD TRCAO ANAIE EPSNR ZMMCI RIDIL RIAGD IOMRI SAEAN VOLEE TBEOR OEEEA SEOEA EERAO OLSLM EAERO ZUHVU ALEEM EONIA AOEEZ CEEON NNESO ANBMI DLFDP LEIIS LQCMT UROIT SRAON EICLL IQCNL LIOIT RFAAN NDMTL ECESN OCOIL STOPA OACIS SAVCN ALARE EAIEC OSBNE OOHPS TSGLO LELDP MNGCM ORNUV LCLJG IINAM AOCAS TSOIL NNELA ONTEE OAAOU LIADO VNSEL RSQAM AOMOS CLVND IUREN TTEEA IIREE FOONN OORAP IYAAT ESLAI INPSO EVARO ARONE OÑNNA IGOSI ZPENA UIAAO LUEOA OERDH SVRTO MEOUI GADLR SDNIR BOESS NDTEA PEMFI LEAUI UEEOD OSSEO RLRDI ILBEU OOLTC NDTAE OSCMO OTASR SYDNO EMLMA EAEIR MIAAA IRUOR LESSC ROULE TARAN ASNÑT UNUDS EOTHC EBEGI OEDTG LOPAL LADAB DLISI SEDOE SRGDO OTODT AROAM CLCBE FDAEA HIAAI LARAE BIBEV AAMNO AIAAE POARO IIEEA EYSAF EEIEP RAGTE ANNOS OPLEA ACEDS IIIDA INZEA INNNC YYAEB EEEPI CENCU TNOSD URJIO LDESA LIITN ODIAI MEORE AEMUP EOCLE EOCAC AOC GDNFP

Things to note about this Sánchez challenge cryptogram:

* There are three 5-letter repeats (OTASR, RLESS, GDNFP), which I think would imply that this is not a simple substitution cipher.

* From the presence of “Ñ”, it seems that the plaintext is probably Spanish or Catalan [Catalan does not have a Ñ letter].

* The most common letters are EAOINRSLTC, whereas the most common letters for Spanish are EAOSNRILDT, and the most common letters for Catalan are EASRLTINOUM.

* Hence it seems that, completely unlike the WW2 pigeon cipher, this is nothing more than a path transposition cipher of a Spanish plaintext.

* The length (in characters) is 1428, which factorises as 2 x 2 x 3 x 7 x 17. [But see the update below!]

* Hence this might feasibly be formed from four sequential transposed blocks of 17 x 21 (or of 21 x 17) characters. [But see the update below!]

* Given that no algorithm is specified, it seems that the cryptogram maker is inexperienced in cryptography and hoping for “security by obscurity”.

Naturally, my normal 15% crypto-consultancy rate applies if you manage to crack it from this. 😉

What Does Nick Think?

What do I make of all this? Well, from all this I hear the clear guiding voice of someone who appears to know almost nothing about how encryption technology works in the real world of heterogenous networks and protocols: there could be no single ‘silver bullet’ that could satisfy the technological needs of encryption in all these areas simultaneously.

So all I can honestly see here is a fake from start to finish, a homegrown transposition cipher cobbled together by someone who has perhaps seen the Feynman Challenge Ciphers (but little else besides), and designed to hype some vapourware (i.e. software which hasn’t yet been written). Do I honestly believe that Sánchez’s allegedly crack team of, errm, code crackers ever existed, never mind cracked ‘our’ WW2 pigeon cipher? No, sorry, I don’t. I really don’t.

So unless anyone has proof otherwise, I call this entire story as a Big Fat Modern Bluff, someone trying to appropriate a real-life cipher mystery to promote some crypto-security vapourware that hasn’t even been written. Would I entrust my data to any company who thinks this is in any way “indecipherable”? No, I would not, sorry.

And this is exactly where I planned to finish the whole coverage of this story…

But Then I Read This…

According to this first part and this second part of detailed Spanish exposé from last September, courtesy of Madrid-based online political daily ‘El Confidencial’:

* Didac Sánchez is just a frontman for a group of companies

* Of those (at least) fifteen companies, only three have so far filed any accounts, with a total combined turnover of less than a million euros, some 2% of the amount claimed in the press.

* The journalists were unable to find any genuine trace of several of the other companies (e.g. Hilton Clinic), despite numerous promises made by Sánchez himself to supply them documentation on the companies’ activities.

* Sánchez’s original name was Diego Giménez Sánchez, but he changed it to Diego Sánchez Giménez

* Sánchez’s real history is to be found in connection with his original name (Diego Giménez Sánchez)

* On 29th May 2005, Diego Giménez Sánchez was (at the age of 12), while living in the Casal dels Infants del Raval in Barcelona, sexually abused by a 45-year-old man by the name of José María Hill Prados. José María Hill Prados was convicted in February 2007 (and banned from contacting Giménez Sánchez for five years or coming within 1000 metres of him), but later appealed, saying that Giménez Sánchez had withdrawn all the claims. However, the court was not swayed by this, or by Sánchez’s many letters (and even TV interviews) at the time. José María Hill Prados has since been released.

* Fast forward to 2015, and El Confidencial’s journalists discovered that the person actually behind all Didac Sánchez’s companies was none other than… José María Hill Prados, whom El Confidencial helpfully labels as “pederasta del Raval”.

Personally, I have no way of knowing what the truth of this matter is. At the very least, the existence of Sánchez / Hill Prados’s company ‘Eliminalia’ that helps people remove their unwanted past from the web is an aspect to this whole affair that is either horribly cynical or spectacularly ironic. Closets have rarely held more skeletons simultaneously, it would seem.

Make of all this what you will. 😐

Update: I just now noticed (*sigh*) the connection with the WW2 pigeon ciphertext – the first five-element code group (GDNFP) is the same as the last (GDNFP). In the case of the WW2 cipher, this is almost certainly because it encrypts the initial settings for the five drums used in the Typex machines used so much by the British Army: but in this challenge cipher, who knows? But this would probably make the length of the ciphertext either (by excluding the final GDNFP) 1423 (which would be a high unlikely message length for a transposition cipher, because it’s prime 🙂 ), or (by excluding both the first and final GDNFP) 1418 which equals 2 x 709, which is also somewhat unlikely as a transposition ciphertext length.

So what is probably going on is that “GDNFP” is encrypting some kind of reordering key to the transposition cipher. If A = 1, then (in ascending order) G = 7, D = 4, N = 14, F = 6, and P = 16. If an idiot programmer was behind this, one might possibly predict that this encodes a five-letter-long hex number (i.e. 0x63D5F = 408927) as the enciphering key. If an idiot mathematician was behind this, these might be indices into a list of prime numbers, A = 2, B = 3, C = 5, D = 7, E = 11, F = 13, G = 17, H = 19, I = 23, J = 29, K = 31, L = 37, M = 41, N = 43, O = 47, and P = 53, so [GDNFP] might instead encode [17,7,43,13,53]. Chances are that these are the kinds of thing this peasanty / homegrown transposition cipher will prove to use.