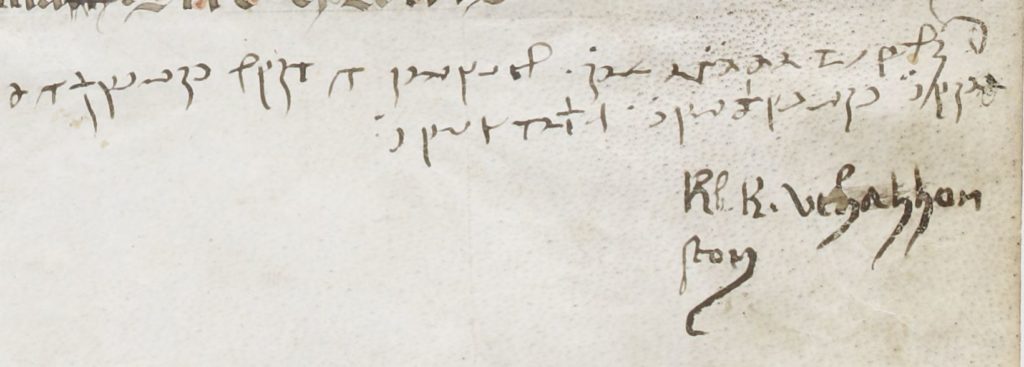

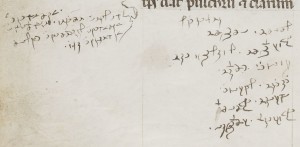

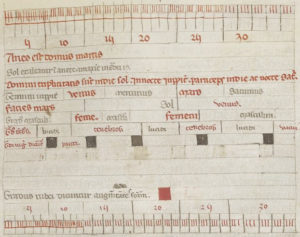

A central pillar of Mormon history is the so-called “Anthon Transcript”, which I have described in reasonable detail on the Cipher Foundations website: this was shown to Professor Charles Anthon in February 1828.

Yet there is a key problem: the description of it given by Anthon in letters dating 1834 and 1841 differs markedly from the image of a “Caractors” page (a document presumably still deep within the LDS’ X-Files-like archive) that is often described as being the “Anthon Transcript”.

In 2012, a better quality image of the same Caractors pages taken around 1884 was discovered in Clay County Museum in Missouri: and this image shows that the full piece of paper then had “The Book of Generation Adam” written on it, which would date it to not earlier than (and probably very close to) 1830.

This implies clearly and unambiguously that there is now no good reason for anyone to think that this “Caractors” sheet is related to the “Anthon Transcript”, simply because it would appear to have been written some two years after Charles Anthon was shown the Anthon Transcript. So there is no logical way that the two items can be the same thing: sorry but they just can’t, and that’s that.

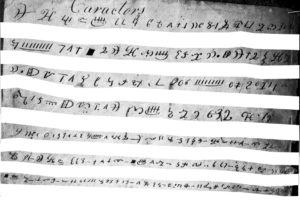

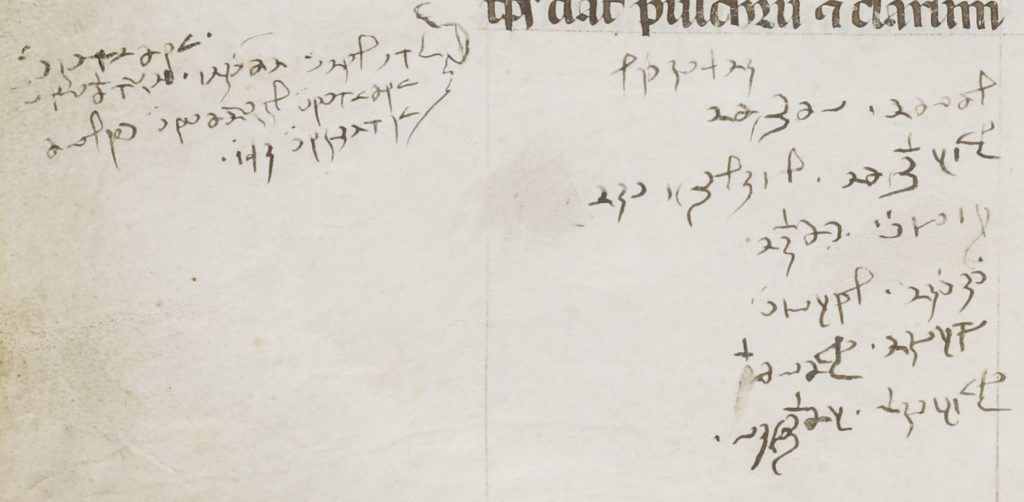

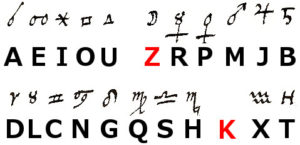

Caractors

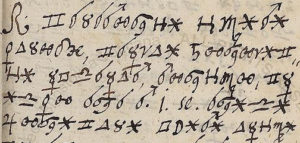

I therefore see no possible theological objection if anyone tries to decrypt the letters on the Caractors sheet: and given that we now have a far higher quality image to work with than we ever did with the original Caractors image, there’s no obvious reason not to give it a go.

So if anyone wants to try, I’ve created a worksheet you can print out and work with (by inserting blank space between the seven lines of text) – just click on the following image to get a reasonable resolution (a higher quality source image would be even nicer, if anyone happens to be passing Clay County Museum in Missouri with a digital camera *hint* *hint*):-

I should caution that it’s hard to be sure what is going on in this page. Though it at first looks like the ungainly mixture of semi-fast shorthand and foolhardily slow-to-write extras (that Isaac Pitman derided as “arbitraries”) that was typical of English shorthands deriving from Jeremiah Rich’s system (e.g. Addy’s etc) and which were still popular circa 1800, further examination makes it clear to me that it’s actually a bit of an improvised mess. As such, its shorthand-like symbols now seems more likely to me to be shapes in a mildly homophonic cipher alphabet than actually shorthand per se.

As always, there’s room for a certain amount of overlap between the two types of writing: but probably not enough to stop anyone from actually breaking it using broadly the same kind of cryptological toolkit.

The Last Sixteen Words

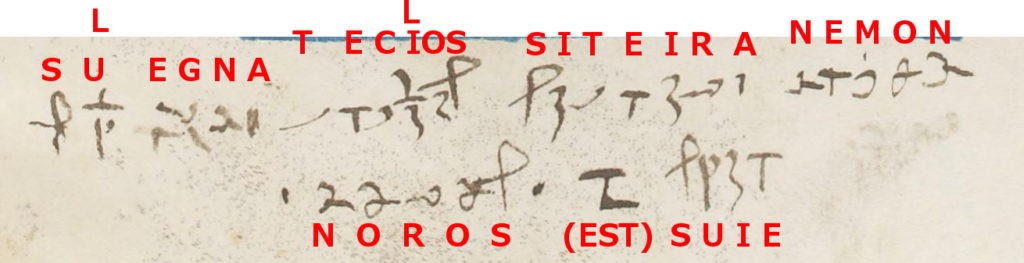

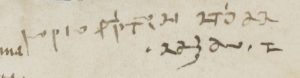

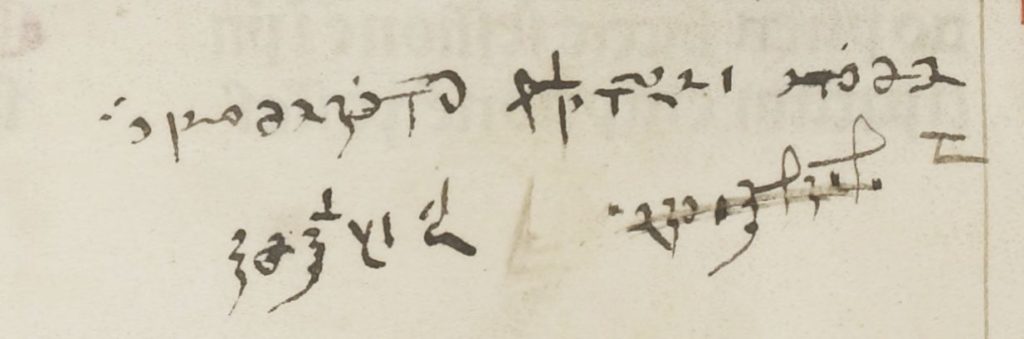

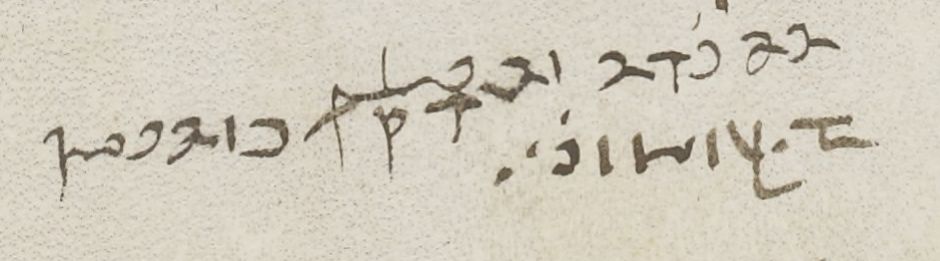

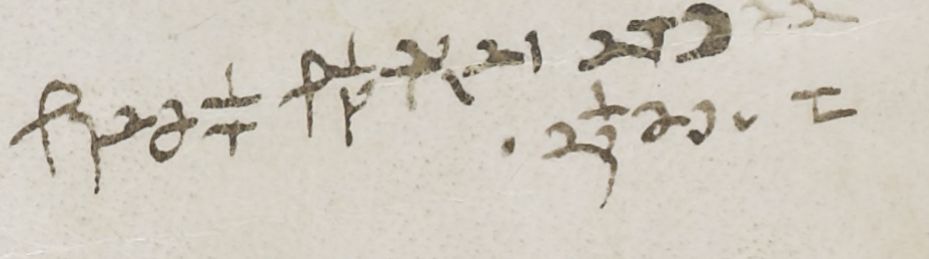

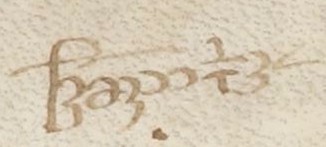

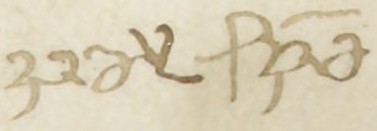

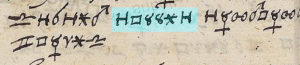

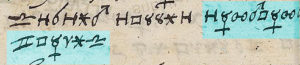

Interestingly, the last three lines (where the text gets smaller and smaller) seem to be written far more systematically than the first four lines. Indeed, there also appears to be a regular use of dashes or hyphens, very possibly as word separators. If you use this to turn the last two-and-a-half lines into a series of sixteen words, this is what you get (click on the following for a much higher resolution image):

Decrypting The Caractors

There is plenty of old-fashioned codebreaking meat to get your cryptological teeth into here: though I’m still trying to resolve the numerous ambiguous / miscopied letter-shape issues, I thought it would be good to give a work-in-progress update on where I’ve got to, in case this inspires someone to crack this (as Marco Ponzi did for the Paris 7272 cipher here the other day).

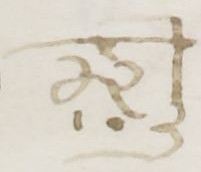

Word #10 is almost identical to Word #6 (though with a letter inserted), which makes the pair of words look like “ONE / ONCE” or some similar phrase (no doubt there are lists of similar ABC / ABDC pairs on the Internet somewhere, please tell me if you know where they are).

The presence of the “6L6” shape in word #1 and word #4 makes it look as though the similar (but slightly malformed) shape in word #15 was the same shape in the original but miscopied: this makes it look to me that much of what we are up against here is miscopying of a simple-ish cipher rather than a genuinely complicated cipher. As such, I suspect that the first letter of word #4 is ther same backwards-crossed-C-C character in words #14 and #15 (and which is the first letter of the top line on the whole page).

Word #12 looks like it may well be a name: but without higher quality scans, I suspect it will be difficult to parse the symbols definitively (some may well be pairs, so it is hard to be sure how many letters we are looking at).

Word #14 and word #15 also offers a cryptographic oddity that might yield a way in: if we use letters to denote patterns rather than actual letters, the two consecutive words would seem to be ABCDE and FGEHAC. Given that there’s a high chance that the plaintext of this page is in some way related to the Bible, I suspect a keenly observant codebreaker with a side interest in Biblical studies might possibly be able to crack these two words alone.

Finally, for those we are interested by the possible connection between the various Whitmers and the Caractors document that has been suggested in recent years, I found a 1989 article that mentioned where the Whitmer family had been to church: “In Fayette [near Seneca Lake, NY], the Whitmers drew closer to God by working the soil and worshipping at Zion’s Church, a German-speaking Presbyterian church“. So there is also a (small) possibility that the plaintext of what we are looking at here might possibly be German. I just thought I’d mention this in passing. 🙂

Good luck!