Over recent years, one topic on which I’ve expended much virtual ink (as well as actual book-buying budget) is that of Bernardin Nageon de l’Estang’s (AKA “Le Butin”, ‘Mr Booty’) letters. But one of the many questions that bother me is: where are these letters? Who owns them?

I don’t yet know the answer: but I believe I can name someone who did once own an actual copy of them…

Loys Masson

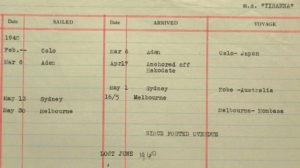

Back in April 2016, I mentioned in a post here that I had found an online reference to a 1935 article in the long-running French literary magazine “Revue des Deux Mondes” that seemed related. However, the specific issue wasn’t available online, so I (once again, are you seeing the pattern yet?) had to spend money on a copy. In fact, it proved cheaper to buy the entire set of magazines for 1935 than a single issue (don’t ask me why).

The author of the article was a young Mauritian poet called Loys Masson: when he (later) arrived in France just as the war properly kicked off, the focus of his work suddenly transformed from a rather elegiac love of Nature into the rather more conflicted (and interesting) topics of war, Resistance and loss.

But you should remember that Mauritius at that time was still a British possession, despite being predominantly French-speaking: which meant that he suddenly found himself (technically) a Briton in occupied France, which required plenty of flexibility to avoid problems. There’s much more about Masson to be found in the book “Loys Masson – Entre Nord et Sud : Les terres d’écriture“, a collection of pieces on him edited by Norbert Louis, who himself contributed a fifty-page summary of Masson’s life and works to it.

But in 1935, it was Masson’s article “La France A L’Ile Maurice” that proved to be his breakthrough piece: the goodwill and interest it raised opened many doors for him, to the point that he could genuinely consider moving from Mauritius to the French literary scene.

His Revue des Deux Mondes piece celebrates the bicentenary of the founding of Port Louis, the capital of the island. More directly relevant to Cipher Mysteries, though, is the fact that in it Masson describes owning a copy of Bernardin Nageon de l’Estang’s letters.

I mentioned this to Norbert Louis, who – though he had seen the 1935 article – was very surprised to find out that the letters to which Masson referred do genuinely exist (he suspected that they were merely Masson’s literary invention), and wasn’t aware of any article or book that discussed these further. So there would seem to be no literature relating to these letters in studies of Masson’s life or works, alas.

What follows is my free translation of what Masson wrote (and which I have transcribed separately and posted on a new Cipher Foundation page):

Masson’s Article

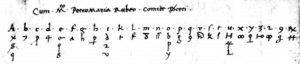

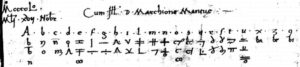

We now make a short stop at the mouth of a stream, a river full of great boulders, where you will have to suffer a nebulous history of treasures. Have they ever existed, these fabulous caches allegedly buried somewhere near the coast? Nobody knows at all. Whether legendary or true, however, there was a time in my family home when numerous Oedipuses found themselves passionately absorbed by these problems. Treasure research was fashionable. Several of my relations threw themselves headlong into it, losing themselves completely. As a child, I recall plans full of cabalistic symbols that one would study by a night lamp, their arrows and crosses traced in a faded ink. As a teenager, I had the good fortune one Sunday to accompany some romantic relatives on one of their treasure-hunting expeditions. Indeed, I saw on large flat stones some of the signs from the documents: here an anchor, there a turtle, and further on were the vestiges of a cryptographic alphabet. Despite our extensive searches, we found nothing. Yet treasure was there, I’m sure. For a long time, I have been in possession of letters from a Sieur Najeon de l’Etang, a veteran corsair, written to one of his nephews in the Seychelles. What remain of these, alas!, are but poor copies. I permit myself to extract some short passages from them for you.

The first is dated 20 floréal an III. “With help from our influential friends, get yourself to the Indian Ocean and the île de France. At the place indicated by my will, climb the river, and then climb the cliff eastward: twenty-five or thirty steps along according to the documents you will find corsair indicator marks to establish a circle of which the river is a few feet from the center. To the north and then four feet south you will find exactly the entrance to a cave once formed by an arm of the river passing beneath the cliff and blocked up by privateers to put their treasure in and this is the vault described by my will…”

The second, “I give to Jean-Marius Justin Najeon de l’Etang, my nephew, namely… treasures recovered from the Indus: I was wrecked in a cove near Vaquois and walked up a river and deposited in a cave the riches from the Indus and marked the place with B. N. my initials… ”

And a third, starting with this almost biblical quote: “Beloved Brother… There are three treasures. The one buried on my dear île de France is considerable. According to the documents, you will see: three iron barrels and jars full of minted doubloons and thirty million ingots and a copper box filled with diamonds from the mines of Visapur and Golkonda…”

What happened to this Croesian cache? Who will tell us? Have we taken completely the wrong route? Only one certainty remains: neither Jean-Marius Najeon nor his descendants solved the riddle. Nor did anyone since. The precious jars and boxes of diamonds, might they have been abducted by an affiliate of the adventurous band? Or do they slumber still in that same dark cave, guarded by a ghostly sentry? The diamond sphinx prefers not to say…

The Differences

What is intriguing is that although extracts from two of the three letters given by Masson are very close (though still not 100% identical) to what we have been working with, the other extract – though overlapping – can only be described as significantly different.

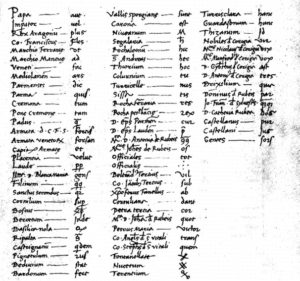

I’ll make the differences there clear, sentence by sentence, by comparing them with the better-known versions of the letters that appeared in “Trésors du monde” by Robert Charroux, Édition J’ai lu (1962):

[Charroux 1962] Par nos amis influents, fais-toi envoyer dans la mer des Indes et rends-toi à l’île de France à l’endroit indiqué par mon testament.

[Masson 1935] Par nos amis influents fais-toi envoyer dans la mer des Indes et rends-toi à l’Ile de France.

[Charroux 1962] Remonte la falaise allant vers l’est ; à vingt-cinq ou trente pas est, conformement aux documents, tu trouveras les marques indicatives des corsaires pour établir un cercle dont la rivière est à quelques pieds du centre.

[Masson 1935] Au lieu indiqué par mon testament, remonte la rivière, remonte la falaise allant vers l’est : à 25 ou 30 pas Est conformément aux documents tu trouveras les marques indicatrices des corsaires pour établir un cercle dont la rivière est à quelques pieds de centre.

[Charroux 1962] Là est le trésor.

[Masson 1935] Au nord donc et à quatre pieds du sud tu trouveras exactement l’entrée d’une caverne jadis formée par un bras de la rivière passant sous la falaise et bouchée par les corsaires pour y mettre leur trésor et qui est le caveau désigné par mon testament.

My Thoughts

Back in 1935, treasure hunting was hugely in vogue – not just in Mauritius, but all over the world. Yet might it have been the case that people were relying on the versions of the letters Charroux later printed in his book, rather than the versions Loys Masson had? Or on yet other copies of those letters?

We don’t know: I know of no retrospective literature on this, and treasure hunters rarely reveal their secrets, even when they – finally, having blown all their personal money and any syndicate money they raised – give up the chase.

More recently, I pointed out that there seems to be strong internal evidence that the final “Beloved Brother…” letter was written by what I called a “missing corsair“, who had inherited the first two documents. If this is correct, it helps give some clarity to what has long been a muddy picture.

Might it be that Loys Masson saw two types of handwriting in his documents, and inferred that they must be copies of older documents, when they could easily have been originals? Unless we ever get to see these (and who owns them now I have no idea, and Norbert Louis had no idea either), we’ll never know.

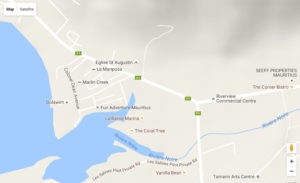

But perhaps modern investigators will be able to use up-to-the-minute techniques to follow the slightly more detailed instructions in Masson’s versions of the treasure documents: to travel up the river from Vacoas, eastwards along a cliff to some pirate marks, northwards then four feet back, before finding the underground cavern hidden by pirates all those centuries before. Might the cache still be where he left it?

Which River Vacoas?

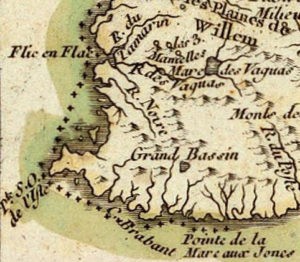

Here’s the south-west corner of Mauritius (“Isle de France”) from a 1791 map:

You can see clearly that there are only two inlets that are near Vacoas. The first (to the right of “Flic en Flac”) collects the Rivière du Tamarin, the Rivière des Vaguas, and an unnamed third smaller river; while the second has only the ominous-sounding Rivière Noire feeding into it.

It would seem logical that the writer of the first two documents believed that he had had been shipwrecked close to the mouth of the Rivière des Vaguas: yet the problem with that is that there are no cliffs whatsoever beside that river.

In fact, only the Rivière Noire runs past cliffs of any size (according to the topographical map I looked at):

Anyway, just so you know… if I was going to go on a treasure hunt here, I’d start by looking at all the early maps of the island I can find. Could it be that Bernardin Nageon de l’Estang confused two different inlets, and so was never able to recover his treasure?

I hear the distant sound of metal detectors being warmed up… who knows where this story may lead?