When is Easter? A simple question, but one with quite a tricky answer: following the decision of the First Council of Nicaea in 325AD, it is the first Sunday after the full moon after the Spring Equinox (which is simplified to be 21st March): hence, Easter can fall anywhere between 22nd March and 25th April.

A moment’s reflection should be ample to reveal what a dog’s dinner of a calculation this entails: and when combined with leap years, calendrical uncertainty, and subsequent calendrical reform, what a practical mess it yielded in the centuries following. Even Carl Gauss got his own Easter-calculating algorithm wrong first time round (and he was no mathematical slouch).

From the early Middle Ages onwards, the awkward task of determining when Easter fell was known as computus – Latin for ‘computation’. In fact, you might (just about) argue that the Nicaean Council’s curious dating mix of pagan festivals, Metonic cycles, astrology and religion provided the original impetus for the modern digital computer – people in the Church had been computing Easter by hand for the previous millennium or so, and were doubtless thoroughly sick of the whole thing.

Given all the above, the obvious historical question to ask is: how on earth did anyone ever manage to calculate Easter? The answer lies in a motley bunch of tables, diagrams, and mnemonics devised, copied and adapted throughout the Middle Ages and early Renaissance that attempt to make the task do-able. For the most part, these are built upon the 19-year cycle of the moon (the Metonic cycle): this means that any time you find yourself looking at an unusual-looking table or diagram in a medieval manuscript that ‘just happens’ to be divided into nineteen columns or segments, there’s a fairly good chance it will turn out to be some kind of computus-based trickery.

The literature on computus is fairly spotty, because (I think) it tends to fall between two stools: basically, it’s too religious to be of interest to many historians of science, but also too scientific for many historians of religion. However, one decent starting point is a 1954 article in Speculum by Lynn Thorndike (one of my favourite historians, as long-time Cipher Mysteries readers will no doubt recall) called simply “Computus” (here’s the JSTOR page for it).

Thorndike had previously written a 1947 paper “Blasius the Franciscan and his Works on Computus” (again, here’s its JSTOR page), in which he discussed Blasius’ “circio” computus mnemonics and their reception in other manuscripts: for example, “CIRCIO” decomposes into CIR = “January 1st, circumcisio domini, the Feast of the Circumcision”, CI = “C, the third letter of the alphabet, which (I think) signifies the third section of the nineteen-year cycle”, O = “O, the 14th letter of the Latin alphabet, hence Easter falls on the 14th April”. Which is to say, in the thirteenth century (probably), Blasius constructed a tricksy Latin-sounding mnemonic that (it seems) replaced one of the computus tables (though note that I haven’t yet read either Thorndike article, so this is just a guess).

But this was not the only similar mnemonic from this time: what became far better known was the “Cisioianus” / “Cisiojanus” mnemonic. Because this spread mainly through 14th and 15th century German woodblock calendars, there’s a fair bit of German-language literature on this, and (for a nice change) the German Wikipedia page on Cisiojanus is actually quite helpful.

Basically, a Cisioianus mnemonic consists of 12 Latin-sounding (but nonsensical) couplets, padded out so that you step through the number of syllables to remember the saint’s days and feasts in that month. Here’s the couplet for January, from where you can see that the mnemonic got its name from the first two ‘words’:-

císio jánus epí ¦ sibi véndicat óc feli már an

prísca fab ág vincén ¦ ti páu po nóbile lúmen

(In case any passing pub quiz pop trivia fans are wondering, Carol Decker’s band “T’Pau” was named after a Vulcan priestess in Star Trek, not after the “ti pau” in the second line here. Just so you know.)

So: because January has 31 days, the couplet for it has 31 syllables, with the feast days highlighted:-

- cí → circumcisio domini, the Feast of the Circumcision

- si → (continuation)

- o → (continuation)

- ján → (a reminder that this is the couplet for January)

- us → (a reminder that this is the couplet for January)

- ep → epiphanias, Epiphany

- í → (continuation)

- si → (null)

- bi → (null)

- vén → (null)

- dic → (null)

- at → (null)

- óc → octava epiphaniae, the eighth day of the Epiphany

- fe → Felicis presbyteris

- li → (continuation)

- már → Marcelli papae

- an → Antoni abbatis

- prís → Priscae virginis martiris

- ca → (continuation)

- fab → Fabiani et Sebastiani

- ág → Agnetis virginis

- vin → Vincentii martiris

- cén → (continuation)

- ti → Timotei martiris und Titi martiris

- páu → conversio Pauli

- po → Polycarpi episcopi martiris

- nó → (null)

- bi → (null)

- le → (null)

- lú → lumen

- men → (continuation)

So, now you know a couplet to remember all the important medieval feast days in January. All you have to do is remember the other eleven couplets and you’ve got the whole year covered, right?

Incidentally, January was named after the two-headed gate-keeper Janus, god of doors and gates (though personally I would prefer it if we had stuck with the Anglo-Saxon “Wulfmonath”, the perishingly cold month when hungry wolves try to enter villages, the original ‘wolf from the door’). And also… Macrobius relates that Roman boys would play with a coin called the “as” (which had Janus on one side and a ship’s prow on the other), calling “capita aut navia?” – (‘heads or ships?’), which presumably morphed into the modern “heads or tails”… but I perhaps have digressed a tad too far here!

Of course, human nature being what it is, people then went on to construct rude and/or ridiculous versions of this basic cisioianus mnemonic that were easier to remember, but that’s a story for another day. 🙂

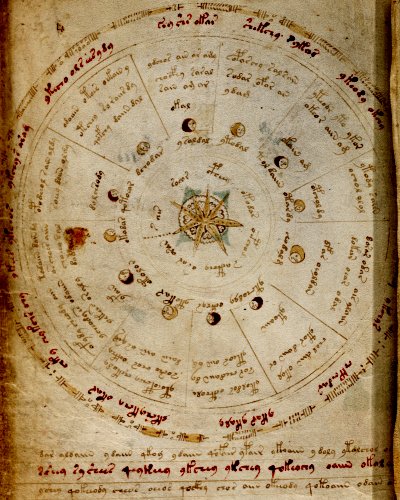

“Fascinating, Nick… but how on earth is this all linked to the Voynich Manuscript?“, I hear you (very reasonably) ask. Well… this all started with an intriguing email from Steve Herbelin, who got the online Voynich / historical research bug a while ago. He had been particularly intrigued by the circular picture on f67r2, which seems to be built around some kind of rational, 12-way division, presumably depicting something calendrical… but what?

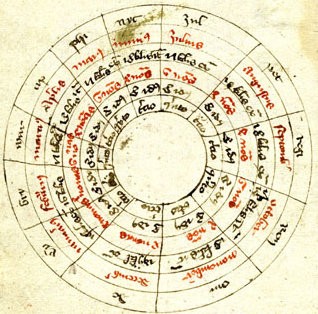

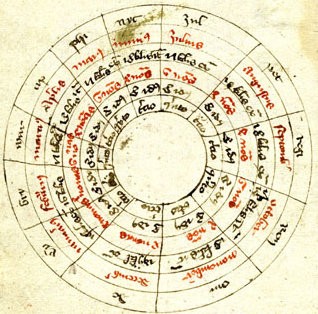

Specifically, Steve wondered if this (or something similar) might reappear in other medieval manuscripts. After some protracted searching, he found this online image from a manuscript from Auxerre from circa 1400 which has plenty of circular computus diagrams (hence all the discussion of computus above), and the following 12-way circular diagram on fol. 9v:-

Decoding this: the outer ring (#1) is a reminder of which cisioianus couplet to use, ring #2 is the month name (“januari9” is at about 8 o’clock), #3 is the kalends, #4 is the nones, #5 is the ides, and the innermost ring (#6) says whether the month belongs to the third (lunar regulars) or fifth (new moon calculation) cycle.

Basically, Steve wonders whether these two images might somehow be part of the same (cladistic / stemmatic) family-tree of manuscripts: that is, whether the text in f67r2’s twelve segments might encipher the same kind of information on the Auxerre MS’s fol. 9v.

Having thought about this for a few days, though the precise details probably don’t quite mesh as well as they at first appear, I really don’t think you can dismiss this comparison out of hand. Mnemonics were useful and not widely known (and so might well fall into the category of “secret practical knowledge“): and it has long been noted that the “medallions” in the centre of the Voynich Manuscript’s zodiac pages do seem to hark back to the kind of illustration you’d find in early German woodblock-printed calendars, so there may well be some kind of reasonably direct influence there.

My own take on f67r2 (The Curse of the Voynich, pp.59-60) has long been that it seems to link a 12-way division around the outside with an 8-way division in the centre, and so (as astrology historian David Juste suggested to me several years ago) could very easily depict or signify some kind of calendrical conversion between a 12-way (lunar) zodiac/administrative calendar and an 8-way (solar) pagan/agricultural calendar. All of which is very neat: but fails to explain the 12 coloured moons or the structure of the text.

Of course, if we could only find the way in which any one ring of the f67r2 diagram enciphers the same information as a ring on the Auxerre MS fol. 9v, then we’d have an almost unbeatably good crib to crack the VMs’ cunning cryptography. However, nothing to do with the Voynich has ever proved to be that straightforward…

For a start, there don’t seem to be 30-31 syllables in each of the 12 segments (however you try to count them), so we can probably rule out a full cisioianus plaintext: so matching this in some abbreviated way would require a bit of thought. Also, I don’t (yet) know the details of Blasius’ “circius” mnemonic, but that might possibly be a better match (as long as it is a 12-part mnemonic rather than a 19-part mnemonic). Furthermore, I can’t see an obvious match with month names (which others have tried to do here for decades), and we don’t even know where the sequence of twelve segments start (or indeed end).

Interestingly, there’s a marginal mark at the top left of f69r2 which came out artificially sharply in the enhanced image above. At full resolution it looks rather messier, but might possibly include a left-to-right-flipped “J” at the bottom:-

Might this be indicating where to start on the diagram; or might it instead signify the start of the quire or chapter? (This was formerly the frontmost page of Quire 9, before it was rebound along the wrong fold, pace John Grove).

At this point, I have to call a halt on this (already far too long) post: once again, I don’t have all the answers, but perhaps I have managed to ask one or two reasonably good questions. All credit to Steve Herbelin!

.jpg)