Over at voynich.ninja, there’s an interesting recent thread on the (in-)homogeneity of Voynichese, i.e. how consistent (or inconsistent) with itself the Voynich Manuscript’s text is (either locally or globally). Given that I have been working on Q20 recently, I thought it might be interesting to take a brief look at that quire through this particular lens.

In Search of a Problem Statement

One intriguing side of Voynichese is that even though it exhibits high-level consistency (e.g. the continuous script, plus the well-known differences between Currier A pages and Currier B pages), medium-level consistency (e.g. thematic-looking sections such as Q13, Q20, Herbal-A, Herbal-B etc), and even bifolio-level consistency (more on this below), there are open questions about the apparent lack of low-level consistency.

In particular, Voynichese ‘words’ (which have been the subject of countless studies and analyses) present many apparent local inconsistencies. As Torsten Timm pointed out in the voynich.ninja thread referenced above, words that are extremely common on one page of a section can be completely absent from the next. And, awkwardly, this is sometimes even true for pages that are the recto and verso sides of the same folio.

Even though there are countless ways to airily explain away these kinds of inconsistencies (change of subject matter, change of source structure, change of underlying plaintext language, change of local cipher key, etc), all too often I think these are invoked more as a research excuse for not actually going down the rabbit hole. (And I for one am bored stiff of such research excuses.)

So, before we start reaching gleefully for such cop-out answers, we need to first properly lock down what the core low-level consistency problem actually is. Basically, what specific behaviours can we point to that indicate that Voynichese has a problem here?

Captain “ed”

It was WWII codebreaker Captain Prescott Currier himself who pointed out nearly fifty years ago that you could usually tell Currier A pages from Currier B pages simply by looking at the proportion of ‘ed’ glyph pairs on that page. (Currier A pages have almost none, Currier B pages normally have loads.)

Personally, I’d add some caveats, though:

- Even though it might be tempting to think of “ed” as a bigram (i.e. a single token), it seems far more likely to be a contact boundary between an “e”-family token (i.e. e/ee/eee) and a “d” glyph.

- To me, there often seems to be something funny going on with qokedy / qokeedy / etc that isn’t really captured by just looking for “ed”

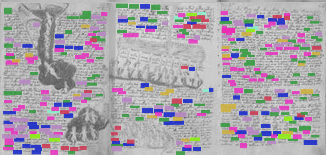

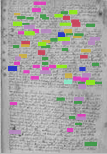

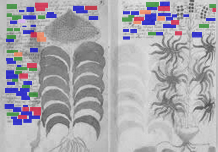

Helpfully, you can use voynichese.com’s layer feature to bring to life the variation in Voynichese words containing “ed”, e.g. this query for lots of different subgroups of “ed” words. Even though Herbal A pages have basically no ed pairs at all, the ed’s nothing short of explode at the very start of Q13:

The first three pages of Q20 are very nearly as colourful:

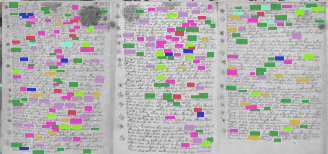

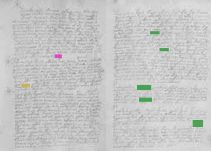

For ed, it seems to be the case that recto and folio pages have a similar kind of ed-density: for example, if you compare f107r/f107v with f108r/f108v, you can see clearly that the two halves of each folio seem quite similar:

The f111r/f111v pair seems to buck this trend slightly, insofar as f111v (on the right) seems somewhat less ed-dense than its recto side f111r (on the left):

While I’m here, I’d note that f116r (the last proper Voynichese page of Q20) seems to have a structure break halfway down, which would be consistent with an explicit and/or a colophon placed at the end of a chapter / book:

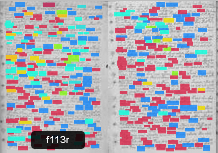

There’s also the question of whether the two folios making up each bifolio appear ed-consistent. I’d say that this appears true for most Q20 bifolios (e.g. f103 and the top half of f116r, f104-f115, f105-f114, f106-f113) but certainly not for others (e.g. f107-f112 and f108-f111). It’s very hard to be definitive about this.

Finally, I’d also note that while Quire 8’s f58r/f58v (with their starred paragraphs) do have some ed-words, their ed-fractions are extremely low, which would make classifying them as “pure” Currier B difficult:

Torsten Timm’s “in”

Torsten Timm has similarly looked at what the usage of the Voynichese glyph pair “in” tells us. Of my own set of voynichese.com experiments, the one that seemed to me to be the most interesting was comparing “iin” with “[anything else]in”.

For example, even though iin dominates [^i]in for most of the Voynich Manuscript, the first folio of Q13 has almost no “iin”s in it at all:

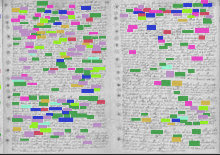

Folio f111 is also a little bit odd, in that its verso side has many more [^i]in words:

“ho”-words Way

As with Currier’s “ed”, “ho” is very much a contact locus between two families of glyphs: on the left, you have ch/sh/ckh/cth/cph/cfh, while on the right you have or/ol/ok/ot/op/of etc. As such, it looks like a useful way of exploring for a group of glyph boundaries, but this does need to be carefully qualified.

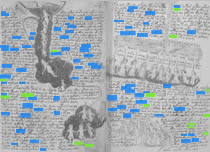

If we visually group this ho-transition (via voynichese.com) in terms of the origin of the “h”, we get a query that looks like this. This reveals that most ho instances are in fact “cho” (dark blue). However, the f93r/f93v folio does look particularly unusual in this respect:

The final two paragraphs of f116r are also unusual, this time for their almost complete lack of ho-words:

If you try to classify ho-words in terms of what follows, you seem to get less predictability.

Putting ed / in / ho Together

From the preceding sections, I’d say that the overwhelming impression I get is that pages within a folio (and indeed pages within a bifolio, though to a slightly lesser extent) are actually reasonably consistent with each other, and with relatively few counter-examples.

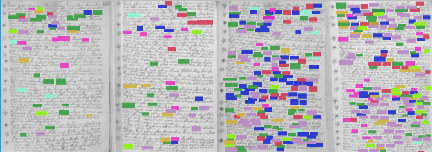

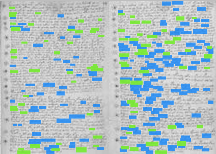

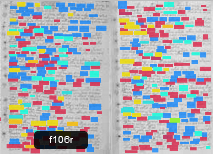

Unsurprisingly, this is also what we see if we simply merge the three ed / in / ho queries into a single voynichese.com query. Here, we can easily pick out the dishonourable exceptions, such as f111 (where f111r is dominated by “ed” [blue], yet where f111v is dominated by “in” [red]):

If we instead highlight cho and sho separately, what emerges is that, unlike the rest of Q20, the f106-f113 bifolio has a surprisingly high proportion of sho-words (in yellow):

I could go on, but I think my visual argument here has pretty much run its course.

Thoughts, Nick?

Even though Torsten Timm used ed / in / ho as part of his argument concluding that Voynichese pages are independent of each other, I’m not sure I fully accept his conclusions. (He’s certainly right about words, but the details and ramifications of that are for another post entirely.)

For me, the behaviour of ed / in / ho seems to suggest something arguably even more unsettling: which is that there seems to be consistency at the bifolio level.

And so it seems that we’re facing a BAAFU (“Bifolio As A Functional Unit”) scenario here. Which is arguably even more mysterious than Currier’s LAAFU (“Line As A Functional Unit”), wouldn’t you agree?

I disagree Nick. You can’t read the text. How are you reading this? The entire manuscript is, as the author writes, = a Jewish substitution.

Further. You will never mix Czech! With English language or Latin or Italian. It is impossible. (Czech is very difficult for an Englishman).

That it is a substitution. The author also drew for you on one side of the manuscript. That’s the bird. Which flies downhill. (the word sup. on that side means = substitution). ( SUP Is a Bird ). ( Sup is an abbreviation of SUBSTITUTION).( phonetics Sup = Sub ). This was commonly written in medieval manuscripts.

If I had to make a wild guess I would say so called Courier A and Courier B aren’t two different ciphers. They use the same signs and you wouldn’t know where each of them starts and ends, it would be unpractical.

I would say there is one cipher but used for sections of different content. Like two languages used.

And if I had to make an even wilder guess I would say these languages could be Latin and some version of German.

In some cases it could be even first part of a sentence begun in some language and finished in another. I don’t have links now but I’ve seen things like that. That would explain pages with “mixed” content

Since the issue has been raised before and I have given my opinion, I will simply repeat it.

I assume that in both cases it is the same language and dialect.

I think one hand, however many people are writing an explanation or procedure to a single person.

“Du nimmst 2 Zwiebeln geschnitten und mischt es”

“You take 2 onions cut and mix it”.

The second hand explains it to a group.

“Ihr nehmt 2 Zwiebeln gehackt und mischt es mit”

“You take 2 onions chopped and mix it with”.

So it would look quite different in German from a purely visual point of view, the content of the text would remain the same.

This is how it looks in German. How would it look in English as an example?

Is it not true that in his later retirement years, post 1976 (DC seminar) Capt. Currier claimed no further interest in his past forlorn obsession with Voynich language complexities. Didn’t he tell either Jacques Guy, Jim Reeds or maybe Mary D’Imperio that, the MS translation was beyond his capacity to fathom, beyond there being at least two languages in the text and, as for how many hands were involved, “pick a number between 4 and 12” .

john sanders: I have no idea what happened with Currier post-1976, sorry. There’s a picture of him in the 1990s, and a brief bio in “U.S. Navy Codebreakers, Linguists, and Intelligence Officers against Japan”. (He died in 1994.)

Nick Pelling: I recall PC being interviewed as an old man maybe living alone and infirm, in his log? cabin somewhere an eastern state possibly New Hamshire. He was very frank about his life and his interest in VM though guarded about his 30 year naval intelligence career. Very interesting, like to read the article again.

….no big deal, Preston Currier died in Demariscota (Lincoln County) Maine Pop. 1200 (pumkins and oysters) near the Canadian border 1995 aged 83. Wrote articles in the WW2 Naval Veterans journal. Will keep looking!

Here are some scientists :https://media.defense.gov/2021/Jul/13/2002761511/-1/-1/0/DAWNAMERICANCRYPTOLOGY_HATCH.PDF

What was trying to crack the voynich. But Captain Presston Currier of the US Navy. There is not.

But Eliška is there. (Elizabeth)

The captain probably didn’t know much, so nothing is written about him.

Oh, and I’ll keep looking.

The thing you say about “bifolios as a functional unit” is very interesting, I had never considered that it could be like that for the text. When it comes to imagery, I have often thought that the VM behaves like a bunch of gathered sheets that seem hardly aware that they are supposed to form a book. For example, in Q13, all four pages of each bifolio appear to belong to the same thematic subsections (or even sub-subsections). The famous connected pipes of 78-81are also on the same bifolio. It’s almost as if they made bifolios separately, which were then gathered into quires as an afterthought. Or were gathered into quires at a later stage? Is it possible to bind a book without nesting?

Koen Gheuens: I remember asking this exact question many years ago, and as I recall the consensus back then was that nesting seemed to be absolutely the cultural norm.

Having said that, when I worked out back in 2006 what the central two bifolios of Q13 originally were, they were definitely nested. Consequently, it’s all rather mystifying – BAAFU makes no sense for bifolios in much the same way that LAAFU makes no sense for paragraphs. “And yet it moves”… 😮

Here’s a fictional-hypothetical scene.

Some threat – war, plague, compulsory orders to leave etc., means that it’s impossible to take a certain library, so the information really vital to the person/family/clan/organisation has to be extracted and copied – fast.

The drawings were made first – we’re all agreed on that, I think(?). The drawings thus provide a basic narrative-plan, to which more detailed information is to be added by the text.

This would make some sense of the fact that the drawings’ sequence os (relatively) more coherent and can run across a sequence of pages.

Next, in this fictional scene, the bifolios with drawings as ‘cue’ are distributed through a number of scribes who must find the expansive matter for labels and commentary from larger, less-portable, volumes in that library (this raises the question of whether the ‘quire numbers’ aren’t actually reference numbers – as vol 1 section 3 rather than quire 1 p.3. That is something unresolvable at present, I think.

So these hypothetical exiles/refugees or whatever take the material in unbound quires to wherever they’re going (this occurring c.1350 or so).

At some later time – presumably around the early fifteenth century, this material which has been further disordered in the meantime (because not bound) is copied *as is* and at that time a couple of excitable scribes mess a bit trying to ‘improve’ the drawings by turning lakes into architectural ‘baths’ on one folio etc.- but that meddling doesn’t last long. A precise copying is what the original fifteenth-century commissioner wanted, and mostly got.

What we end up, then, in this fictional scenario, is a coherent collection of drawings that are mostly consistent though a given narrative such as the ‘bathy-‘ section (though not remotely about going bathing), and yet pages that display a variety of scribal hands and evidently more than one underlying language, despite all being in a script (possibly genuine, possibly created) whose set of glyphs is maintained fairly consistently throughout. Different languages/dialects/topics in the original library-volumes then account for the oddly patchwork-like presentation of the written text.

As I say, the story is fiction but if the model serves, might help get a grip on what seem so many contradictions in the evidence.

For me, I’ve been thinking lately about the fact that Voynich studies has always assumed, tacitly or consciously, that the informing text must derive from an ‘alphabetic’ tradition – that by analysing our written text we can get direct access to the original language as ‘plaintext’.

But what if that’s not so? What if we need to change from focus on writing to language-as-spoken.

Hmmm.

Happy New year to all.

D. N. O’Donovan: I prefer my hypotheticals short and to the point. Simply put, the Voynich Manuscript, named for the author of course, was a subtle message to all the fake book dealers/buyers in America that his F. U. B. L. (Finest Un-listed Biblios London) company was in town to do business, year being 1912.

I just thought about Nick’s theory once. Let’s assume that f58 is the introduction to Quire 20. If the page is turned, it would also be the end of plants ( large ). When I look at the pictures of the plants, there are those that have been painted very conscientiously with colour. Now it could be that the clean plants were first, and in a second part the somewhat botched ones, or even without paint and later painted to increase the price of the book.

The other way would be f58 is not the introduction to Quire 20, but the introduction to Astronomy. Thus the plants would be the end of the herbal part

Diane, what you write in the initial part of the entry is most consistent with what I think about the cause and effect genesis of the Voynich Manuscript. More, it is a clue to follow in order to understand the uniqueness of this work – given the historical context of those times (earlier liquidation of the Templar order, religious wars in the early fourteenth century, and the like).

Short and to the point hypotheses have dominated the thinking of various home-grown cryptologists for several centuries, and nothing but the ridiculousness of argumentation has so far not resulted from it.

John,

I don’t appreciate narrative fictions being imposed on any historical artefact. In my field, it’s usually Yoda all the way. You know, “Either know or not know, grasshopper”.

Sure, for mathematicians, cryptologists, theoretical physicists.. hypothesising is an essential tool in their work.

Very rarely though creating a fictional model to understand how a sequence of events *could* occur, can help.

Grzegorz,

The delicate business of forming an historical hypothesis is something else again.

Nick has spoken to that issue in earlier posts. From beyond the confines of Voynich studies, Tim O’Neill has done so more recently – Nov.29th., 2022.

That post is certainly sharp, absolutely to the point and (as a result) not very short.

With Nick’s permission, here’s the link to that post:

https://historyforatheists.com/2022/11/how-history-is-done/?utm_source=rss&utm_medium=rss&utm_campaign=how-history-is-done

Diane: physical theories might be hypothetical and math incomplete and not total consistent as axiomatic system. But it sounds as if you are claiming a deductive superiority for your domain (“know or not know”)… or I get you wrong and you only suggest to do like natural scientists do. More science is definitely what the whole VMS investigation needs and, sorry for all historians, cryptology is at first a mathematical discipline, then comes linguistics and history is the last to consult.

Have a good year altogether.

Darius – it’s simpler than that.

If someone is paying for an opinion, they are entitled to know a lot more than just your opinion; they’re entitled to know step-by-step the evidence and developing argument, and they are entitled to be affronted if told they should believe whatever they are told. In the Voynich world, the opposite is true.

I’m speaking only of the quasi-historical narratives and assertions made about the drawings.

A hundred years of handwriting research and you’re still at the beginning. A scientist should ask himself a question. Why am I at the beginning of manuscript research? Where am I going wrong when examining the manuscript? So does my work have any meaning? Wouldn’t it be better to pursue another activity? Will I ever be successful in manuscript research?

Any scientist working on the problem of MS 408. They should sort it out in their heads. That means putting it together. And then dive back into your problem. Or if he discovers that, for example, ten years of his work does not bring any results, then stop the research.

If he wanted to continue. So it is important for him to keep an open mind and read carefully what I have written for example.

Above all, a scientist should not read what was written about a manuscript a hundred years ago. That won’t help him and he’ll be at the start anyway.

Holy Trinity:

In our galaxy and in general in the entire universe known to us, everything depends on: 1. Information.

2. Energy.

3. Matter.

_________________________________________________

1.Impulse (that’s me) I give you information.

2. Work (it’s you and your energy) So try.

3 The result (of your work).

Josef prof. Many people on this site underestimate you, but for me you are either a madman or a genius…. or a brilliant madman… or a mad genius…. Choose what you want… :))

In this last statement of yours “breaks off” something that some might call – The Theory of Everything.

John 1:1

In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God.

1. In the beginning was the Word – Information.

2. and the Word was with God, – Energy.

3. and the Word was God. – Matter.

Josef, many people on this site underestimate you, but for me you are either a madman or a genius…. or a brilliant madman… or a mad genius…. Choose what you want…

In this last statement of yours “hides” what some might call – The Theory of Everything.

John 1:1

In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God.

1. In the beginning was the Word – Information.

2. and the Word was with God, – Energy.

3. and the Word was God. – matter.

Diane: I suppose mostly there is only one step, so step-by-step would be then impossible. I include myself into this criticism, but I started to make up for it.

Prof: you are a pitiless judge, like YHWH described on 102v. Did you read my 102v translation? But one remark: rest mass (say matter) and energy are essentially the same thing as we know from😛, so we could put 2) and 3) together. Otherwise, why to start a new Trinity debate, after 1700 years…

Josef (if I may)

In Voynich studies, unless people read what was said a hundred years ago, they do not realise how very short a way the study has really come, or understand that some wise-sounding and ‘inspiring’ pronouncement is no more than parroting a couple of lines from an old, old idea that went no-where then and will go no-where again if they’re misled by it.

For example, the idea of the ms as containing neoplatonic matter is Newbold’s idea – perhaps his own, perhaps ultimately from Richard Garnett, before 1906.

Similarly, the idea that the leaf-and-root section contain medieval European pharmacy jars is total nonsense from both the historical and the archaeological evidence. It too was Newbold’s notion – and it was obviously wrong even in the 1920s, but many people believe it still.

Don’t touch it until you know where it’s been is a good motto in this study.

@Diane. ( I can )

MS 408 is not a Neoplatonic mass. 🙂

Otherwise what someone Newbold or Garnett wrote is very wrong. It’s clear from their research that they didn’t know much. Something like you. Even you can never decipher the text of the manuscript. You can only parrot what you read somewhere. And be here on these pages of Mr. Pelling. Or elsewhere on the web. You are limited to only reading what someone somewhere has posted. Because you can’t think for yourself. That’s your big problem. Of course I don’t blame you. It’s your destiny.

And how you change different information on your blog based on what you read here is ridiculous. Like yours: copyright applies. 🙂

Where do you say it’s not about pipes? 🙂 But that they are body organs. 🙂

Why don’t you just write that they are veins. 🙂 And you can also write there that I revealed it to you. Josef Z.