A recurring motif running through my own Voynich research is trying to grasp what happened to the manuscript over time. If you examine it carefully, you’ll find plenty of good reasons to think that its original (‘alpha’) state was significantly different to its final (‘omega’) state. My strong hunch is that if we were able to reconstruct how the manuscript looked in its original state, we would take a very different view on how it ‘worked’ or ‘functioned’ as an object – and so I keep on gently digging away at the marginalia and codicological clues, to see what subtle stories they have to tell us, what secret histories are betrayed by their presence.

Of course, to many (if not most) Voynich researchers this is just too arcane a way of looking at what (to their eyes) is simply a cryptological or linguistic conundrum. Each to their own, eh? But all the same, here’s a new angle to think about…

In a previous post, I discussed the so-called “chicken scratch” marginalia on f66v and f86v3, with a codicological aside that…

[…]if you reorder Q8 (Quire #8) to place the astronomical (non-herbal) pages at the back, and also follow Glen Claston’s suggestion by inserting the nine-rosette quire between (the reordered) Q8 and Q9, what you unexpectedly find is that the f66v and f86v3 chicken scratches move extremely close together. If this is correct, it would imply that the doodles were added very early on in the life of the VMs, probably earlier even than the fifteenth-century hand quire numbering (and hence probably early-to-mid 15th century).

However, I think this chain of reasoning can be extended just a little further. Why do these chicken scratch marks only occur on these two pages and nowhere else? I suspect that the most likely reason is that the two pages were not only (as I noted) “extremely close” to each other but also – at the moment that the chicken scratches were accidentally added to the manuscript opened out on someone’s (Simon Sint’s?) writing desk – were probably on two pages facing each other.

Yet the paradox here is about how this ever could have been, given that both marginalia are on verso pages.

Now, for normal two-panel bifolios, the assignment of “r” (recto) and “v” (verso) is unproblematic – the recto side is always the page nearest the front of the book, while the verso side is the page nearest the back. However, if you instead look at wider-than-two-panel bifolios and consider rebinding the panels along different edges, pages can change their orientation (facingness) and hence can change between verso and recto.

So, because f66v is part of a normal two-panel bifolio, for it to have originally been a recto page requires that it was on a wider bifolio that was trimmed down to two panels and then rebound… and there’s no obvious reason to think anything like that happened. Hence, I think we can reasonably infer that if the two chicken scratch pages did originally sit side-by-side, f66v was on the left hand side of the pair.

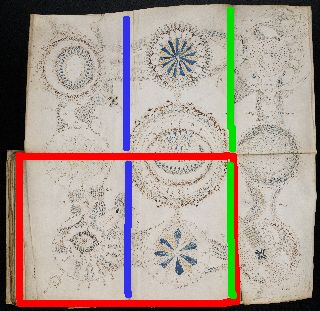

Looking at f86v3, however, we see that it is on the back of the Voynich’s infamous “nine-rosette” drawing, which comprises a large 3 x 2 set of panels that fold out. Moreover, Voynich researcher Glen Claston has proposed that at some point in its history, this quire (Quire 14) sustained significant damage along its original binding crease (green, below) and so was rebound along a different fold (blue, below).

And guess what? If you were to bind Quire 14 along the green line, make the big horizontal fold first (as it is now), and keep the blue fold internal (i.e. exactly the way it is now), the page which would sit right at the front of Q14 is (you’re way ahead of me) f86v3. And because f86v3 also has the Q14 quire mark (near the bottom right), this would give yet more support to the idea that the VMs was reordered and rebound before the quire numbers were added. Also, you can see the raggedy edge of the damaged binding on the left-hand side of f86v3:-

Now: I should add that a fair while back Glen Claston alluded to having three separate pieces of evidence that supported his claim that Q14 was originally folded and rebound along the green line, and it may well be that this whole chicken scratch argument was one of them. Well, I for one don’t mind playing catch-up with such a sharp brain as his. But hey, I got there in the end! 🙂

One nicety then becomes whether Q14 was bound into this position, or whether the whole codex was no more than an unbound set of gatherings in its early existence: but if the crease suffered significant damage (as seems apparent) when Q14 was removed from the codex, it must have been bound into position before being removed, surely?

All the same, there is one further problem to consider: if both sets of chicken scratches were added when the manuscript was open at a single page, then something must have happened to Q8 before then – because the f66v chicken scratches are on the back page of Q8 in its final order, not its original order.

This points to a number of hypothetical codicological timelines to evaluate, such as:-

Scenario #1

- The manuscript is assembled. The two bifolios of Q8 are (relative to their current orientation) inside out and back to front, with f58v on the back page. Q14 is inserted immediately afterwards (but with the primary fold along the blue line). Q9 immediately follows (also with the primary fold different what we see now).

- Q8 is reversed, leaving f66v on the back of the quire (next to f86v3)

- The manuscript is bound with Q8 reversed

- The chicken scratches are added

- Q14 is removed (damaging the binding) and rebound with the other outside quires. Q9 is also rebound to be less “flappy”.

- Quire numbers are added

Scenario #2

- The manuscript is assembled. The two bifolios of Q8 are (relative to their current orientation) inside out and back to front, with f58v on the back page. Q14 is inserted immediately afterwards (but with the primary fold along the blue line). Q9 immediately follows (also with the primary fold different what we see now).

- Q14 is removed and accidentally reinserted into the middle of Q8, placing f66v next to f86v3.

- The manuscript is bound in this order

- The chicken scratches are added

- Q8 is reversed, leaving f66v on the back of the quire

- Q14 is removed (damaging the binding) and rebound with the other outside quires. Q9 is also rebound to be less “flappy”.

- Quire numbers are added

Personally, I’m rather more convinced by the first scenario (mainly because it seems a slightly simpler sequence) – but you may well have your own opinion. Still, at least it’s an issue that could be codicologically tested (by checking sewing stations, contact transfers etc). The secret history of chicken scratches! 🙂

Some interesting points.

Additionally, if you search for the EVA character “x”, I count only 19 folios within the entire manuscript that contain it. (46r,55r,57v,66r,85r,86v6,94r,104r,105r,105v,106v,107v,108r,108v,111r,112r,113v,114v,115v). Speculating, this symbol may have only been used for a short time (beginning, middle or end) during the construction of the VMS, thus the above folios would appear to be linked in time. It seems reasonable that all of the EVA “x” folios would be in the same group, namely Quire 8. Not a hard leap given that Quire 8 already has herbals, thus could absorb 46r, 55r and 94r. Also, all of Quire 20 fits as well given the “star” markers found on f58r/v. The only odd link was Quire 14, of which you have now made a decent case above. Thus, when trying to fit the codicological puzzle, a grouping with EVA “x” seems plausible.

FYI…I still don’t see Simon in the “chicken scratch”, no matter how I flip it around.

TT

Tim: given that f109 and f110 are missing (I expect Baresch sent this innermost bifolio to Kircher), this is pretty good coverage of Q20 – in fact, every folio apart from the first folio and the last folio contains ‘x’es. Just a thought… could it be that Q20’s outermost bifolio has different content to all Q20’s inner bifolios? Furthermore, might the outermost bifolio have originally been tacked on as an afterthought? I’ve always thought that f103r was somewhat implausible as a first page, and f105r (with its overelaborate initial gallows) a much likelier candidate.

So, could it be that the ‘x’es are telling us that the original bifolio ordering for Q20 was more like:-

/—f105

| /— f106 (say)

| | /— f107

| | | /— f108

| | | | /— f104

| | | | \— f115

| | | \— f111

| | \— f112

| \— f113

\—f114

/—f103

\—f116

Co-incidentally, f103 and 116 are linked as they are the only folios in Q20 that do not have tails on the stars ( I’m sure I’m not the first to see that), but it does seem odd that they are also the ones without the “x”es, as you point out above.

Also, if you look at F105r and 115r, the top few para’s appear darker…as if the beginning and end of the Q20 work was bounded by a different pen. Curious why you put 115 in the middle.

TT