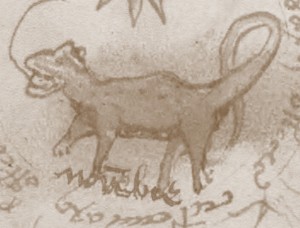

While snooping around the (mostly empty) user subsites on Glen Claston’s Voynich Central, I came across a page by someone called Robin devoted solely to the Scorpio “Scorpion” page in the VMs. This has an unusual drawing of a scorpion (or salamander) at the centre, and which I agree demands closer attention…

My first observation is that, while the paint in the 8-pointed star is very probably original, the green paint on the animal below is very likely an example of what is known as a “heavy painter” layer, probably added later. But what lies beneath that?

Luckily, there exists a tool for (at least partially) removing colour from pictures, based on a “colour deconvolution” algorithm originally devised (I believe) by Voynich researcher Gabriel Landini, and implemented as a Photoshop plugin by Voynich researcher Jon Grove. And so the first thing I wanted to do was to run Jon’s plugin, which should be simple enough (you’d have thought, anyway).

However… having bought a new PC earlier in the year and lost my (admittedly ancient) Adobe Photoshop installation CD, Photoshop wasn’t an easy option. I also hadn’t yet re-installed Debabelizer Pro, another workhorse batch image processing programme from the beginning of time that I used to thrash to death when writing computer games. If not them, then what?

Well, like many people, I had the Gimp already installed, and so went looking for a <Photoshop .8bf plugin>-loading plugin for that: I found pspi and gimpuserfilter. However, the latter is only for Linux, while the former only handles a subset of .8bf files… apparently not including Jon Grove’s .8bf (I think he used the excellent FilterMeister to write it), because this didn’t work when I tried it.

For a pleasant change, Wikipedia now galloped to the rescue: it’s .8bf page suggested that Helicon Filter – a relatively little-known non-layered graphics app from the Ukraine – happily runs Photoshop plugins. I downloaded the free version, copied Jon Grove’s filter into the Plug-ins subdirectory, and it worked first time. Neat! Well… having said that, Helicon Filter is quite (ready: “very”) idiosyncratic, and does take a bit of getting used to: but once you get the gist, it does do the job well, and is pleasantly swift.

And so (finally!) back to that VMs scorpion. What does lie beneath?

And no, I wasn’t particularly expecting to find a bright blue line and a row of six or seven dots along its body either. Let’s use Jon’s plugin to try to remove the blue as well (and why not?):-

Well, although this is admittedly not a hugely exact process, it looks to me to be the case that the row of dots was in the original drawing. Several of the other zodiac pictures (Gemini, Leo, Virgo, Libra, Sagittarius) have what appears to be rather ‘raggedy’ blue paint, so it would be consistent if Scorpio had originally had a little bit of blue paint too, later overpainted by the heavy green paint.

And so my best guess is that the original picture was (like the others I listed above) fairly plain with just a light bit of raggedy blue paint added, and with a row of six or seven dots along its body. But what do the dots mean?

I strongly suspect that these dots represent a line of stars in the constellation of Scorpio. Pulling a handy copy of Peter Whitfield’s (1995) “The Mapping of the Heavens” down from my bookshelf, a couple of quick parallels present themselves. Firstly, in the image of Scorpio in Gallucci’s Theatrum Mundi (1588) on p.74 of Whitfield, there’s a nice clear row of six or seven stars. Also, p.44 has a picture of Bede’s “widely-used” De Signis Coeli (MS Laud 644, f.8v), in which Scorpio’s scorpion has 4 stars running in a line down its back: while p.45 has an image from a late Latin version of the Ptolemy’s Almagest (BL Arundel MS 66, circa 1490, f.41) which also has a line of stars running down the scorpion’s back. A Scorpio scorpion copied from a 14th century manuscript by astrologer Andalo di Negro (BL MS Add. 23770, circa 1500, f.17v) similarly has a line of stars running down its spine.

In short, in all the years that we’ve been looking at the iconographic matches for the drawings at the centre of these zodiac diagrams, should we have instead been looking for steganographic matches for constellations of dots hidden in them?

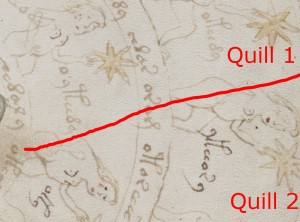

Incidentally, another interesting thing about the Scorpio/Sagittarius folio is that the scribe changed his/her quill halfway through: which lets us reconstruct the order in which the text in those two pages was written.

Firstly, the circular rings of text and the nymphs were drawn for both the Scorpio and Sagittarius pages. The scribe then returned to the Scorpio page, and started adding the nymph labels for the two inner rings, (probably) going clockwise around from the 12 o’clock mark, filling in the labels for both circular rows of nymphs as he/she went. (Mysteriously, the scribe also added breasts to the nymphs during this second run). Then, when the quill was changed at around the 3 o’clock mark, the scribe carried on going, as you can see from the following image:-

What does all this mean? I don’t know for sure: but it’s nice to have even a moderate idea of how these pages were actually constructed, right? For what it’s worth, my guess is that these pages had a scribe #1 writing down the rings and the circular text first, before handing over to a scribe #2 to add the nymphs and stars: then, once those were drawn in, the pages were handed back to scribe #1 to add the labels (and, bizarrely, the breasts and probably some of the hair-styles too).

It’s a bit hard to explain why the author (who I suspect was also scribe #1) should have chosen this arrangement: the only sensible explanation I can think of is that perhaps there was a change in plan once scribe #1 saw the nymphs that had been drawn by scribe #2, and so decided to make them a little more elaborate. You have a better theory about this? Please feel free to tell us all! 🙂