In a comment to a recent post on Alberti & Averlino, ‘infinitii’ asks what my recommendations would be for a Voynich Manuscript reading list… a deceptively hard question.

Apart from the direct literature on the subject (Mary D’Imperio’s “An Elegant Enigma”, my “The Curse of the Voynich”, and perhaps even Kennedy & Churchill’s “The Voynich Manuscript”), probably the best first step would always be to buy yourself a copy of “Le Code Voynich” – not for its prolix French introduction *sigh*, but simply so that you can look at the VMs’ pages in colour. The best guide to the manuscript still remains the evidence of your own eyes. 🙂

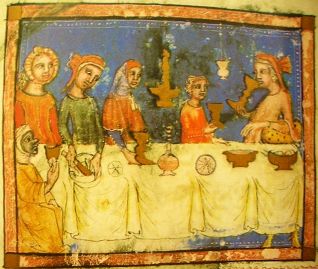

All of which is the easy, lazy blogger answer: but the kind of proper answer infinitii alludes to would be much, much harder. I should declare here that the VMs’ life in Bohemia (and beyond) strikes me as merely a footnote to the main story (though admittedly one that has been interminably expanded, mainly for lack of proper research focus).. Given that I’m convinced (a) 1450 is pretty close, date-wise; (b) Northern Italy is pretty close, location-wise; and (c) it’s almost certainly some kind of enciphered book of secrets, then the main subject we should be reading up on is simply Quattrocento books of secrets.

Doubtless there are three or four literature trees on this that I’m completely unaware of (please tell me!): but as a high level starting point, I’d recommend Part One (the first 90 pages, though really only the last few touch on the 15th century) of William Eamon’s “Science and the Secrets of Nature” (1994). Unfortunately for us, Eamon’s main interest is in Renaissance printed books of secrets. “In Nature’s infinite book of secrecy a little I can read” (Shakespeare, Antony and Cleopatra), indeed. 🙂

From there, you’ll probably have to drill down (as I did) to individual studies of single books. Virtually everything written by Prager and Scaglia fits this bill, such as their “Brunelleschi: Studies of His Technology and Inventions” (1970) and “Mariano Taccola and His Book De Ingeneis” (1972). I recently blogged about Battisti and Battisti’s splendid “Le Macchine Cifrate di Giovanni Fontana” (1984), and that is also definitely one to look at (though being able to read Italian tolerably well would be a distinct help there). I’ve also read articles by Patrizia Catellani on Caterina Sforza’s “Gli Experimenti” (which has a smattering of cipher in its recipes), and read up on the possible origins of Isabella Cortese’s supposed “I Secreti” (which is about as late as I’ve gone). Beyond that, you’re pretty much on your own (sorry).

As general background for what secrets such books might contain, I can yet again (though I know that infinitii will groan) only really point to Lynn Thorndike’s sprawling (but wonderful) “History of Magic & Experimental Science” (particularly Volumes III and IV on the 14th and 15th century), and his little-read “Science and Thought in the XVth Century”. Thorndike’s epic books stand proud in the middle of a largely desolate research plain, somewhat like Kubrick’s black monoliths: if anything else comes close to them, I don’t know of it.

As far as Quattrocento cryptography goes, David Kahn’s “The Codebreakers” is (despite its size) no more than an apéritif to a book that has yet to be written. I found Paolo Preto’s “I Servizi Segreti” very helpful, though limited in scope. For Leon Battista Alberti’s cryptography, Augusto Buonafalce’s exemplary modern translation of “De Cifris” is absolutely essential.

What is missing? There are a few relevant books I’ve been meaning to source but haven’t yet got round to, most notably the century-old (but possibly never surpassed) “Bibliographical Notes on Histories of Inventions & Books of Secrets” by John Ferguson. You can buy an updated version with an index and a preface by William Eamon, for example from here.

In many ways the above is no more than a very personal selection of books, and one obviously based around my own particular research programme / priorities. Yet even though I have tried to cover the ground reasonably well over the last few years, there are doubtless large clusters of (for example Italian-language) papers, books and particularly dissertations I am completely unaware of.

It should be clear that I think the basic research challenge here is to build up a properly modern bibliography of Quattrocento books of secrets, and thereby to map out the larger literature field within which the whole idea of ‘the VMs as an enciphered book of secrets’ can be properly placed. Perhaps I should use this as a test case for open source history?