Diane O’Donovan recently stumbled across a reference to a relatively little-known Italian-Jewish engineer / cryptographer / magician called Abraham Colorni (Abramo Colorni) who was for a short while at Rudolf II’s court: and wondered aloud (in some comments to Cipher Mysteries) what we might learn from his 1593 book on cryptography.

“Scotographia etc etc”

As you might expect, Colorni’s book title is badly afflicted by the prolixity so typical of the age: “Scotographia, ouero, Scienza di scriuere oscuro, facilissima, & sicurissima, per qual si voglia lingua : le cui diuerse inuentioni diuisi in tre libri, seruiranno in più modi, & per cifra, & per contra cifra : le quali, se ben saranno communi a tutti, potranno nondimeno usarsi da ogn’uno, senza pericolo d’essere inteso da altri, che dal proprio corrispondente”. That is, “Scotography, or the science of concealed writing, most easily and most securely, etc etc etc“.

Various physical copies exist: MIT Library, in the Cryptology Collection of UPenn’s Van Pelt Library (I always wondered what happened to Lucy), Harvard Library, BnF, the British Library, the Hungarian Academy of Sciences’ Library, Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, and the Klau Library at Hebrew Union College in Cincinatti to name but eight. There are also microfilm copies at Herzog August Bibliothek and the British Library, if squinting into dusty old back-lit magnifying boxes floats your boat.

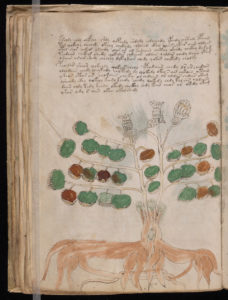

Obviously, what you’d actually like to know is what online versions exist. The BNCF website includes only a ragged copy of the first couple of folios of MAGL.3.8.24, which is not that impressive:

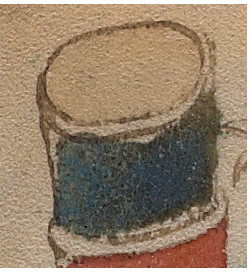

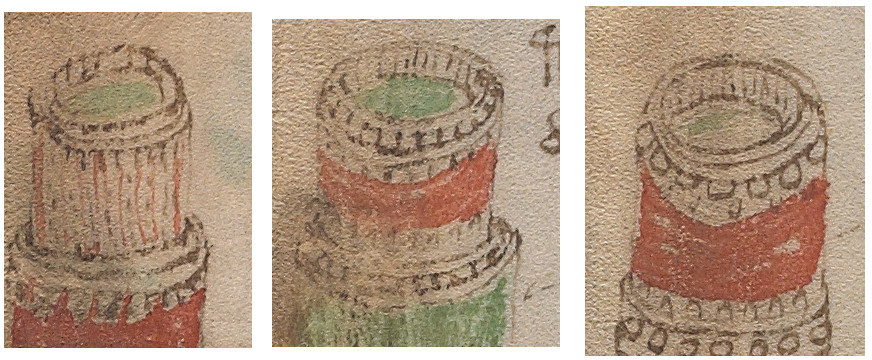

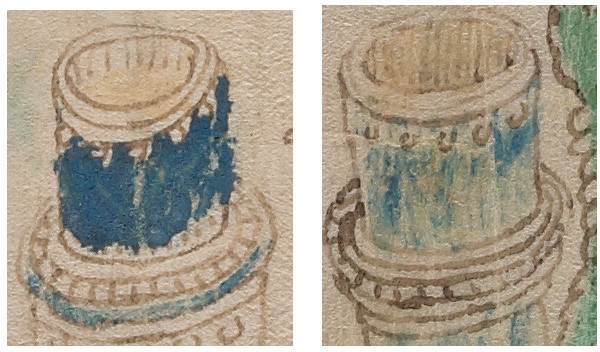

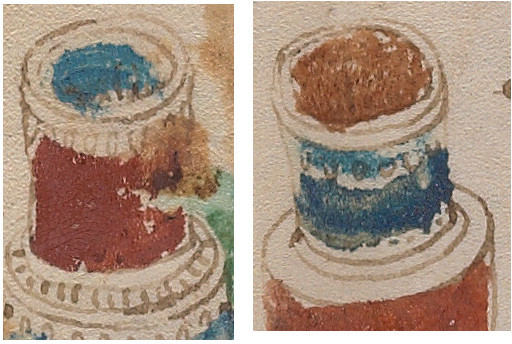

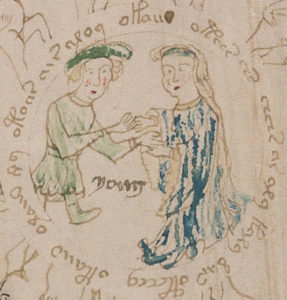

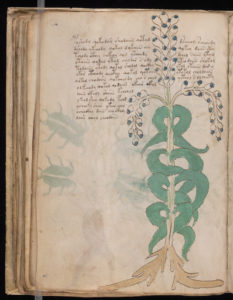

The Museo Galileo’s website has a complete set of scans of the BNCF MS, though (perhaps because the whole book has an unusual aspect ratio, i.e. it’s much wider than it is tall), all the Museo’s scans have come out vertically stretched by a factor of three in their reader (the “Reader” icon at the top of the page). This is also true of the PDF download option, e.g. how it is (left) and how it ought to be (right):

Alternatively, you can read the same pages from the index webpage, though only one at a time, and the (unstretched) image goes off the right hand edge of the web page unless you really widen the size of the browser window, which is annoying in a quite different way.

Having said that, none of this is fin du monde etc.

The Book’s Contents

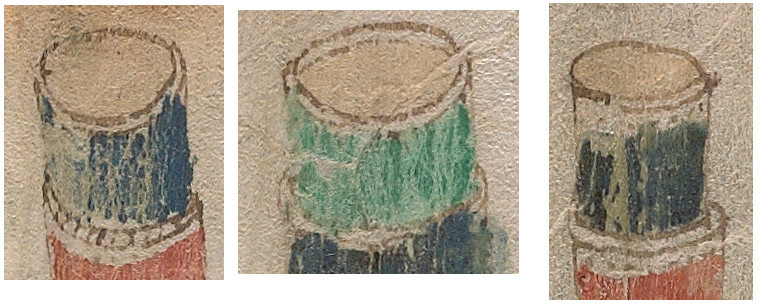

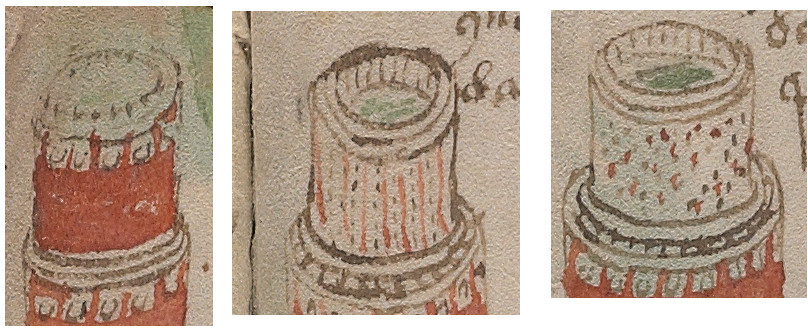

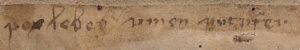

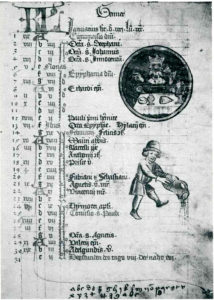

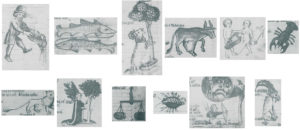

As normal, the book starts with a seven-page laudatory preamble praising Colorni’s most magnificent patron, Holy Roman Emperor Rudolf II, and explaining the symbolic meaning behind the four specific zodiac signs chosen for the frontispiece (Scorpio, Libra, Virgo, Leo):

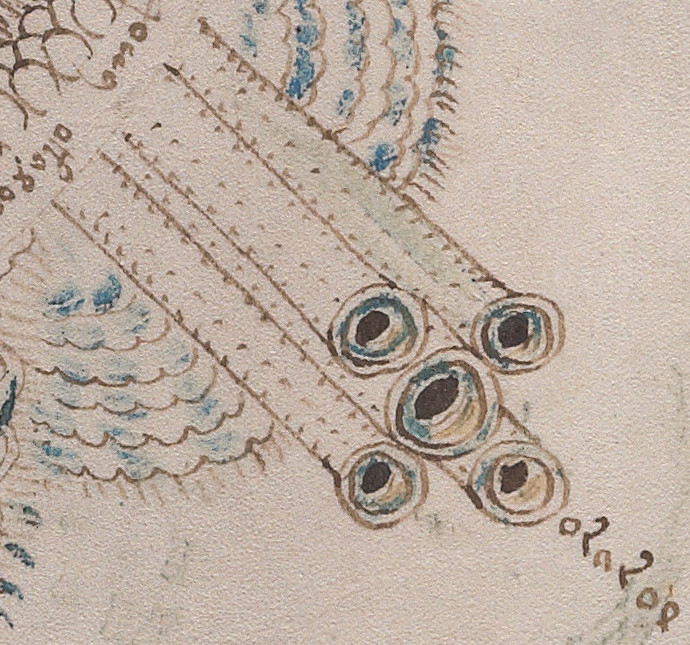

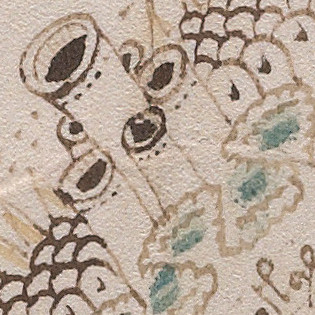

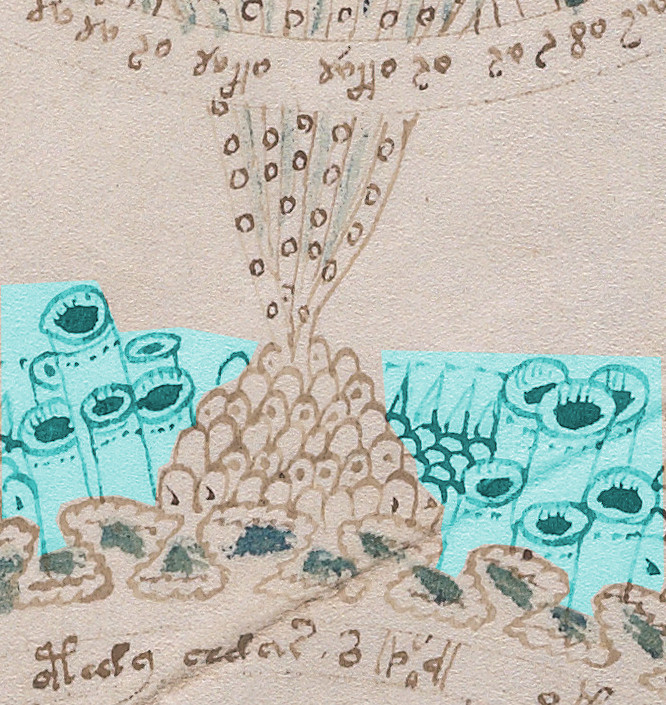

The book continues with three main chapters (though the middle chapter is tiny), and then finishes up with an enormous enciphering table (more than half the remainder of the book). It also includes some interesting cryptographic figures which I don’t recall seeing elsewhere.

From what I have read, it seems to me (and feel free to correct this impression) that Colorni was not a theoretical codemaker or codebreaker. Though his cipher history account starts with the normal SCYTALE (long thin message wrapped around a stick) cipher yarn, his writing doesn’t seem informed by the work of contemporary crypto theoreticians such as Bellaso.

Rather, I suspect what happened was that Colorni collected together a series of cryptographic tricks (such as nulls, verbose cipher, etc) and then adapted and extended them into something cunning and ingenious which he believed to be practically impregnable. So I think his book (to answer one of Diane’s questions) documents various cunning “peasant ciphers” rather than being part of a theoretical crypto mainstream.

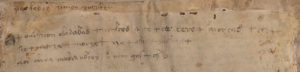

Incidentally, just about the only ciphertext given in Colorni’s book (there are no challenge ciphers) is:

GWGHPCXKGBEDMMYWOPWQPWO

HMAAHXNAYLPKOOBPXKFFLTGWYIXG

Feel free to try to crack it if you wish. 🙂

Colorni and the Voynich Manuscript?

But, Diane continues, might it have been Abraham Colorni who brought the Voynich Manuscript to Rudolf II’s Golden Court in Prague? Superficially, Colorni would certainly seem to tick many of the boxes, and there’s unlikely to be evidence out there that explicitly proves that he didn’t bring it. (After all, what are the chances a letter now turns up saying “It wasn’t me, Abraham Colorni, who sold that scandalous naked women cipher book to the Emperor, it was that blasted John Dee“?)

All the same, I don’t believe that Colorni’s book’s introductory dedication to Rudolf II (written in 1593) mentions anything sounding at all like the Voynich Manuscript (as always, please feel free to correct me if I’m wrong). It does namecheck Oedipus, but presumably for broadly the same reasons that Georg Baresch also (independently) namechecked Oedipus several decades later.

Perhaps a more productive route to take would be to look at Colorni’s correspondence, and see if that casts any light on the subject. And, very helpfully, there are (at least) two freely downloadable 19th century articles by Professor Giuseppe Jarè that might assist us in this regard:

- Abramo Colorni : ingegnere Mantovano del secolo XVI. ; con documenti ined.

- Abramo Colorni : ingegnere i Alfonso II. d’Este ; memoria letta nell’ adunanza 30 marzo 1890

Both articles include transcriptions of a number of letters (in both Latin and Italian) culled from numerous archives. In fact, the second article contains so many that I suspect that Jarè must have had Colorni as an ongoing research interest for some twenty years or more.

Though some of these definitely mention Colorni’s Scotographia, I didn’t notice anything related to the Voynich Manuscript in there. However, others more observant and diligent than me may have more luck: and wouldn’t that be nice? 😉

Secondary Literature on Abraham Colorni

Though I’ve tried to limit my discussion here of Abraham Colorni to primary evidence, there is also a pretty good modern literature on him if you’re interested:

- The age of secrecy : Jews, Christians, and the economy of secrets, 1400-1800 – Daniel Jütte

- Or, in German: Das Zeitalter des Geheimnisses : Juden, Christen und die Ökonomie des Geheimen, (1400-1800) – Daniel Jütte

- Trading in secrets : Jews and early modern quest for clandestine knowledge (Isis, Vol. 103 (2012), p. 668-68)

- Il prestigiatore di Dio : avventure e miracoli di un alchimista ebreo nelle corti del Rinascimento – Ari’el To’af – Milano : Rizzoli, 2010

- Rene Zandbergen also points out there is a chapter on Colorni by Vladimir Karpenko in:Alchemy and Rudolf II, Exploring the Secrets of Nature in Central Europe in the 16th and 17th centuries, edited by Ivo Purš and Vladimír Karpenko, Artefactum, Prague (2016), though probably building on Daniel Jütte’s book.

A Needle In A Haystack?

For twenty-plus years, Rene Zandbergen and a whole host of others have invested a lot of time into trying to dig up references / historical evidence relating to the Voynich Manuscript’s (probable) time at Rudolf II’s court: but have so far found nothing.

From what I know, I don’t currently believe that Abraham Colorni will turn out to be the missing link, the “Herald” (in Joseph Campbell / Hero’s Journey terms): rather I think that if it did make its way to Rudolf II’s court, it was very much towards the end of his rule (notionally at Rudolf II’s death in 1612, but he was under a kind of house arrest by his brother Matthias for the last few years – families, eh, who’d have ’em?). And with Colorni dying in 1599, the two therefore probably didn’t overlap in Prague.

All the same, I find Professor Giuseppe Jarè’s articles hugely heartening, because he was able to collect together from a whole list of archives all manner of correspondence relating to Colorni: and that gives us access to a evidential slice cutting through Colorni’s life.

So perhaps the right thing to do, Voynich-wise, is to stop looking for a needle in a haystack – i.e. a single perfect piece of evidence – and to instead start looking for a sewing box in a haystack. By this I mean collections of diligently-collected letters and documents not unlike Jarè’s collection of Colorni’s correspondence, but for technical-minded court insiders who were at Rudolf II’s court nearer the end.

The best attempt at doing this so far has been by looking at the correspondence between Duditius and Tadeáš Hájek z Hájku (1525-1600), who was Rudolf II’s Imperial Astronomer, as studied by Josef Smolka (with help from Rene Zandbergen). I previously discussed their lack of (Voynich-related) success here, and concluded that the 1600-1612 period might be more fruitful.

But do we have a list of people who we might even consider as candidates for this kind of search? One would have thought that the 15 volumes of Tyco Brahe’s correspondence (in Tychonis Brahe Dani Opera omnia) to 1601 would have been thoroughly mined by Voynich researchers by now. Christoph Rothmann (of Kassel) similarly died in 1600, while Caspar Peucer died in 1602. Even so, I suspect we are likely to have no luck with any of them.

Has anyone trawled through Kepler’s correspondence looking for partial or indirect references to the Voynich Manuscript? I’m thinking that perhaps the best way forward would be to look at the network of correspondents linked to Kepler in the 1600-1615 period. The letters between Kepler and Galileo are well-known, but they surely can’t make up even 25% of Kepler’s correspondence, right?

Perhaps one of these letter writers will have heard mention of the Voynich Manuscript: and perhaps this is how the first big piece in the Voynich jigsaw will be found, who can say? 🙂