Back in 2001, David Hockney proposed a radical new take on art history: that around 1430, artists began to use a camera obscura arrangement to focus images onto a canvas. This was to help them attain a level of draughting accuracy not available to artists who were simply “eyeballing” (Hockney’s term) a scene. The key paintings he employs as evidence for this claim are Jan Van Eyck’s ultra-famous “Arnolfini Portrait” (1434) and Robert Campin’s “Man In A Red Turban” (circa 1430) [though it’s not actually a turban but a “chaperon” – bet you’re glad you know that].

What is unavoidably odd about these Flemish pictures is that they suddenly aspire to a level of representational precision that had no obvious precedent – the technique of oil painting (developed much earlier) was suddenly refined and heightened in these artists’ apparent quest for almost (dare I say it) photographic imagery. Hockney sees all this as posing the implicitly technological question “How did they do that?” (particularly things like van Eyck’s highly complex chandelier, which has neither underdrawings nor construction marks): his own answer is that they must have used some unspecified (and now lost) optical means to assist them. But what?

Initially, this seems likely (he argues) to have been a convex mirror (though somewhat confusingly Hockney calls this a “mirror-lens”) within a camera obscura arrangement: but its technological limitations (particularly the small size of the projected image and the shallow depth of field) would only have allowed them to project one depth slice of one picture element at a time; and so would have required a kind of sequential collage effect to build up a complete composition. Much later (In the 1590s), the mirror was apparently (Hockney asserts) replaced by a lens, with Caravaggio’s two drunken Bacchuses held up as evidence (a “before-the-lens” and an “after-the-lens” pair, if you will).

Much of the scientific support for Hockney’s claim was provided by depth-of-field and relative size calculations by Charles Falco. Hence it has become known as the “Hockney-Falco thesis”. Really, it is a bold, almost aggressively naive technological-centred re-spin of art history, which sees photography merely as the modern version of a roughly 600-year-old tradition of optically-assisted realistic representation. By all rights, the entire hypothesis should be horribly wrong, with (I would guess) the majority of art historians on the planet looking for a way to help it sink into the sand upon which it appears to be be built. However, it has (quite surprisingly) proved remarkably resilient.

Actually, many of the criticisms are well-founded: but most seem to be missing the point. Hockney isn’t an art historian (not even close), but a practitioner: praxis is his matrix. Here, he is in the business of imaginative, empathetic knowledge production – which is a necessary part of the whole knowledge-generation cycle. Hockney repeatedly falls into many of David Fischer’s “Historians’ Fallacies” when trying to post-rationalize a narrative onto his observation: but given that historians often follow these same antipatterns, it is hardly surprising that an accidental historian such as Hockney fails to avoid them too.

Admirably, Hockney tried to respond to many of his critics by bringing together an intriguing selection of from primary sources on optics and the camera obscura (not dissimilar to the second half of Albert van Helden’s splendid “The Invention of the Telescope”). And so the “new and expanded” 2006 edition of his (2001) “Secret Knowledge: Rediscovering the lost techniques of the Old Masters” has appended English translations of many relevant historical texts (Bacon, Alhazan, Witelo, Manetti, Leonardo, Cardano, Barbaro, Della Porta, etc), as well as correspondence from 1999-2001 between Hockney and various people (mainly the very excellent Leonardo expert Martin Kemp, who squeeze in several satisfyingly good whinges about academe along the way).

OK: enough folksy summarizing, already. So, what do I think about all this?

For a start, this obviously cuts a path right through a lot of my ongoing research interests – Quattrocento secret knowledge & books of secrets, the mirror+lens combinations, early camera obscuras, Renaissance proto-telescopes, the emergence of modern optics 1590-1612. So I ought to have an opinion, right?

In a way, the unbelievable technical prowess of the Old Masters – their sheer blessèd giftedness – has been so much of a given for so long that to have David Hockney waltz in & undermine that is quite shocking. And all credit to Martin Kemp for grasping so early on that this points to such a potentially significant sea-change in the tides of academic art history.

I’m hugely sympathetic to Hockney: I did a bit of painting (though many years ago), and I have a professional interest in camera optics & the subtle problems of image perception – so I can see very clearly the artefacts in the paintings upon which he and Charles Falco are focusing. In a very important way, that’s the easy bit.

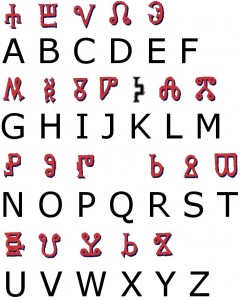

Yet one of the problems I have with the correspondence reproduced at the back of the book is that it gives the overwhelming impression that Hockney is all too ready to leap to the conclusion that the Church would deem this kind of image capturing a new kind of heresy: that that which is not understood must be occult. This exact same non-argument template (along the lines of ‘if the evidence isn’t there, it must have been suppressed for being heretical’) gets trotted out ad nauseam for many other hard-to-explain historical mysteries (perhaps most notably for the Voynich Manuscript): and, quite frankly, turns me right off every time I see it.

But the reason for this is obvious: the quality of the non-pictorial evidence Hockney cites to support his case is generally rather poor. He simply doesn’t have a smoking gun – nor even a non-smoking gun, really. He’s reduced to speculating about the nature of the mirrors Caravaggio owned when he died: and, frankly, that’s not really sufficient. When he can’t even point to a single substantive mention in a single pre-1500 letter or document, it’s easy to see why the whole hypothesis remains speculative (historically speaking).

I suspect one good question that should be asked is instead about the quality of the translations we are all relying upon to form our critical judgments on this. When tackling an early modern passage, translators must first conceive what kind of thing is being talked about when trying to give the text a shape comprehensible to our modern mindsets. And when something as basic as using curved mirrors as a painting aid has only just entered our collective awareness, I think it is likely that almost all translators of primary sources would have fudged over difficult or obscure passages. And so the ‘absence of evidence’ may ultimately have arisen from a missing conceptual framework in translators’ minds.

For what it is worth, my best guess is that there will turn out to be some primary evidence to support Hockney’s ideas, but that it won’t be a new passage: rather, it will turn out to be a known passage that was subtly mistranslated. But which should we be reassessing?

I’ve checked Thorndike (as you would) and Sabine Melchior-Bonnet (of which Hockney seems blissfully unaware) for ideas: the latter discusses Parmigianino’s “Self-Portrait in a Convex Mirror” (1524) on p.227, which should contain sufficient information for an optical historian to reconstruct the size and focal length of the mirror used. She gives many other leads: for example, Fioravanti discusses mirrors in his “Miroir des arts et des sciences”, and there is yet more discussion in Salomon de Caus (1576-1626)’s book “Perspective avec la raison des ombres et des miroirs”. Yet ultimately, if there is a smoking gun, it probably sits waiting to be found in 15th century letters and books of secrets.

Regardless of how much moral support it gains, Hockney’s hypothesis continues to stand parallel to the art history mainstream: it awaits a truly daring art historian to look again at the sources, and to tease out the subtle behind-the-scenes narrative. This kind of reconstructionist approach (not unlike Rolf Willach’s take on telescope history) yields one kind of evidence – but only one, and so this is not the whole story. Life is never quite that simple…