In late 1944 to early 1945, America was assailed by 9000+ Japanese Fu-go constant-altitude balloon bombs flying high over the Pacific, the mulberry-papered ICBMs of the era. Though their explosions caused few deaths and little physical damage, the US Military was terrified that these balloons might instead be repurposed to carry Bacteriological Warfare payloads. Furthermore, contrary to the impression you might get from Ross Coen’s book on Fu-go balloons, a bacteriological attack is exactly what some in the Japanese military – mostly notably General Ishii Shiro, founder of the notorious Unit 731, and who seems to have had the Emperor’s ear – were pushing hard to do next.

But then WWII ended, and so the threat of trans-Pacific balloon-based anthrax attacks on North America receded too. Yet many in the US Military remained impressed with the low-cost ingenuity of the Fu-go balloons, and wondered whether balloons might be a tech trend in future warfare the US should be following.

By 1950, the US had started developing its own (anti-crop rather than incendiary) balloon bomb technology, the E77 balloon bomb. So… what exactly happened between 1945 and 1950?

The Amazing Piccards

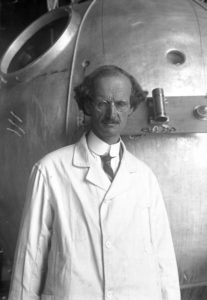

Even before WWII, balloon technology was racing forward. In 1936, Swiss-born balloon pioneer Jean Felix Piccard flew a 25-feet (7.6m) diameter cellophane balloon built by his students in Pennsylvania: others were attempting much the same thing in Germany and Belgium. In 1937, Jean Piccard also flew the first cluster balloon (made of 98 latex balloons).

And so, after the war, it was entirely natural and obvious that Piccard, now working with Otto Winzen, would in February 1946 propose to the US Navy the best of both worlds – a cluster balloon made of plastic balloons, designed for human flight. In June 1946, this proposal was approved and became Project Helios. By 1947, this morphed into Project Skyhook, which was used both for unmanned high altitude experiments and for manned lower altitude experiments.

Yet it all parallels the work done by Jean Piccard’s twin brother Auguste Piccard, who in 1930 created a spherical pressurised aluminium gondola, and in 1931 used it to become one of the first two people to reach the stratosphere. And then, in an amazingly Jules Vernean way, Auguste then used broadly the same kind of pressurised gondola to travel deep below the ocean, with the first unmanned trips happening in 1948.

And yes, you’d be right to guess that Gene Roddenberry named the Star Trek character Jean Luc Picard after one or both of these intrepid Piccard twins, Trek canon loosely implying that he was their descendant bla bla bla. But what you probably wouldn’t also know is that Hergé modelled Professor Cuthbert Calculus on the lanky Auguste Piccard, though reduced his height “otherwise I would have had to enlarge the frames of the cartoon strip“. So today you get not only a Star Trek reference but also a Tintin reference.

1946 – Project Helios

The core idea of Project Helios was to use clusters of plastic balloons for prolonged high-altitude (stratospheric) manned ballooning. The aim was to carry out experiments at 30,000m for up to 10 hours, thanks to the huge amount of weight saved by replacing (heavy) latex balloons with (light) plastic balloons.

By way of support, Jean Piccard designed his own pressurised gondola with a 52-inch diameter octagonal floor and two escape hatches: this was later built by Winzen Research, Inc. and General Mills. Unsurprisingly, Jean Piccard was rather hoping to pilot this gondola himself. Also: rather than placing the individual balloons in serial, Piccard designed a quite different kind of clustering assembly that instead placed them in parallel.

On 25 September 1947, they launched the first large balloon since the end of World War II. The first in a series of four launches, the polyethylene balloon had a capacity of 100,000 cubic feet (2,832 cubic meters), but carried only 70 pounds (32 kilograms) of equipment. The next two test launches failed. On the fourth launch, the balloon refused to descend for three days, and the high-altitude controls, radio equipment, and insulated containers malfunctioned. The delay was a goldmine for cosmic ray researchers. Two Brookhaven National Laboratory physicists, J. Hornbostel and E.O. Salant, had flown a pair of cosmic ray plates on the mission, and they were delighted with the results that the three-day delay brought. The success of their experiment led the ONR to abandon the idea of human balloon flights and focus on unmanned research.

A different account mentions briefly (p.4) that:

Project Helios […] was called off because it was impossible to meet safety standards adequately. There was not enough known at the time of the capabilities of the plastic, and it was considered foolish to risk a human life in the face of many uncertainties.

The same account notes that L.Cdr. M. Lee Lewis had been working on balloons with Jean Felix Piccard since 1946, while this account mentions the ONR’s Commander George Hoover as having been involved with the project.

1947 – Project Skyhook

Presumably building on what the US Navy had learned from Project Helios, Project Skyhook was then started up with a specific initial focus on using polyethylene balloons for unmanned balloon experiments.

It is usually claimed that the first Skyhook launch, using a single balloon built by General Mills, took place on 25th September 1947 in St Cloud, Minnesota. This carried a 29 kg payload of nuclear emulsion to higher than 30,000m, before landing in Eau Claire, Wisconsin. Yet because this is obviously the same Project Helios balloon described above, I suspect that the boundaries between Project Helios and Project Skyhook are somewhat fluid.

Similarly, the first Skyhook cluster balloon launched (using three polyethylene balloons) in 1948.

Incidentally, when the fourth 1947 balloon flight failed to land as planned, this had unexpected social consequences:

On October 20, 1947, one balloon was not recovered and startled Minneapolis residents as it hung 100,000 feet over the city.

In a University of Minnesota News Service press release, Adeline B. Melcher, the college’s chief switchboard operator, stated that “the switchboard was jammed with calls for an hour from worried persons who wanted to know if there was a flying saucer in the sky or if it was the beginning of the end of the world.”

Finally, if you’re desperate for another cultural reference, I’d add that the 1956 film “Earth vs. the Flying Saucers” mentions “Project Skyhook”. Which is nice.

1947 – Project Mogul

In parallel with the US Navy’s projects (Helios and Skyhook), the US Army was developing its own balloon-based projects. Project Mogul comprised both an unclassified (ballooning) side and a classified (nuclear test detection microphone) side, which stayed secret until 1972.

There’s a list of 1947 Project Mogul test launches in Saler, Ziegler and Moore’s (2010) debunk-fest “UFO Crash at Roswell: The Genesis of a Modern Myth”, which gives an idea of how the Mogul team’s experiments evolved during that year:

- #1: 3 April 1412 EST, Bethlehem, Pa. 14 balloons in train, each 350 g. Radiosonde and sand ballast.

- #2: 18 April, time unknown, Bethlehem, Pa. 23 neoprene balloons in train. Sonobuoy, radar targets, radiosonde, and sand ballast

- #3: 8 May, time unknown, Bethlehem, Pa. 23 neoprene balloons in train. Same as Flight #2.

- #4: 4 June (~0300 MST), Alamogordo, N.Mex. 28 neoprene balloons in train. Same as Flight #2, plus liquid ballast dribbler but minus radiosonde

- #5: 5 June, 0516 MST, Alamogordo, N.Mex. 28 neoprene balloons in train. About same as Flight #2, plus liquid ballast and minus radar targets

- #6: 7 June, 0509 MST, Alamogordo, N.Mex. 28 neoprene balloons in train. Same as Flight #5, but dribbler lost at launch

- #7: 2 July, 0521 MST, Alamogordo, N.Mex. 16 neoprene balloons in Helios cluster. Microphone, radiosonde, and ballast

- #8: 3 July, 0303 MST, Alamogordo, N.Mex. Ten 7-ft-diameter GMI (General Mills, Inc.) [balloons]. Microphone, radiosonde, and ballast balloons in Helios cluster.

- #9: 3 July, 1930 MST, Alamogordo, N.Mex. 16 neoprene balloons in Helios cluster. None launched.

- #10: 5 July, 0501 MST, Alamogordo, N.Mex. 15-ft-diameter polyethylene balloon, Microphone, radiosonde, and liquid ballast.

…and so forth.

Putting aside Charles Moore’s unreliable narration regarding the 4th June 1947 #4 flight (which according to Crary’s log book, wasn’t launched at all etc), what is visible here is the Mogul project team’s move not only from Pennsylvania to New Mexico, but also from using neoprene to polyethylene, along with using Project Helios balloon clustering information (i.e. taken from the US Navy Helios project).

In 2000, Air Power History published an article by James Michael Young on “The U.S. Air Force’s Long Range Detection Program and Project Mogul“. The Mogul programme had been initiated by General Carl Spaatz, and ran test flights until Spring 1949. The NYU group’s remit (their contract was signed on 1st November 1946) was “to design, develop, and fly constant-level balloons to carry instruments to altitudes ranging from 10 to 20 kilometers, adjustable at two-kilometer intervals. The goal was to maintain an altitude within a 500 meter variance and to eventually sustain that altitude for 48 hours.” (p.27)

Note that at that time nobody in the NYU group knew anything about the classified part of the project: and it’s not at all clear to me from the article whether the Air Force’s AFOAT-1 project (started July 1948, and which ended up being the classified half of Project Mogul) was already somehow in place when Project Mogul was started in 1946.

1950 – E77 Balloon Bomb

The kick that propelled crop-based Bacteriological Warfare (BW) back on the US Military’s untasty war weapons menu was the Stevenson Committee, that in 1950 reported its findings a mere five days after the North Korean invasion. Hawkishly, the committee thought that BW should be considered not just as defensive weapons, but also for offensive weapons. (p.72)

This is the precise context when the E77 balloon bomb was commissioned: even though the technological ideas behind it were stolen from the wartime Japanese Fu-go balloon bombs, it was now intended to fight a war in Korea. Hence it now seems far from obvious to me that there was any kind of related US Military balloon bomb development going on between 1945 and 1950: or, rather, if there was any continuous development in that period, I’ve yet to see even a flicker of a sign of it.

Note: it might seem odd that even though we’ve seen US Army balloons and US Navy balloons, we have seen no US Air Force balloons. However, it’s important to point out that the US Air Force was only separated out from the US Army on 18th September 1947 (prior to that time it was the “US Army Air Force”). Which is basically why I have been jumping through hoops to say “US Military” prior to this date, *sigh*.

Holloman AFB and Balloons

There are a few more crumbs to be had in the history of Holloman AFB published in 1959. This confirms that the first successful rubber cluster balloon launch from there was on the 5th June 1947 (i.e. Flight #5, not Flight #4 as incorrectly claimed by Charles Moore). This flight lasted six hours; rose to a maximum of 58,000 feet; and was successfully recovered just east of Roswell NM.

Similarly, the first polyethylene cluster balloon launch from Holloman was on the 3rd July 1947 (i.e. Flight #8). Here, the payload was about fifty pounds; the flight lasted 195 minutes, and reached 18,500 feet; but the recovery was unsuccessful.

At Holloman AFB, the Balloon Branch (the part of the air force at the base who travelled out to collect landed balloons) was formed in 1949, though it informally existed beforehand as the “Balloon Unit”. There are pictures of the Balloon Branch’s vehicles parked up near junctions, waiting to zip off and recover landed balloon payloads.

What’s Missing From This Picture, Nick?

The point of trying to put together this kind of technology timeline is almost always to see how things link together, and where any documentary gaps are. For me, the biggest gap here relates to the US Navy’s Project Helios. There was obviously interaction between the Navy’s Project Helios team and the Army’s Project Mogul team, because the latter switched from using serial linkage (“in train”) to Jean Felix Piccard’s Project Helios parallel cluster linkage on their flight #7 in July 1947.

I can’t easily believe that the Project Mogul people would have switched to using Project Helios parallel cluster linkage if it hadn’t already been properly tested. Yet we have not a single record of a Project Helios test flight.

Really, I can’t help but wonder if the difference between Project Helios and Project Skyhook is that (a) Project Helios ended up being a codeword for all the early experiments that went disastrously wrong, and which had to be quietly buried; and (b) Project Skyhook was code for all the good bits of Project Helios that were then carried forward and used for many years (with more than 1000 balloon flights, in fact).

Hence I’m more than a bit suspicious that Project Helios did in fact have some kind of (possibly fatal) accident in 1947 that had to be covered up – which might explain the somewhat awkward talk of meeting “safety standards adequately” noted above.

Hence I’m now left wondering where to look for Project Helios documentation. I tried the Jean Felix Piccard special collection at University of Minnesota, but almost all the interesting material there seems to stop around 1942. And I had a poke around in NARA, but I found nothing there remotely interesting from that time period (I emailed the archivists to ask if there was something I missed). So… where next for Project Helios archives?

For Piccard family papers (including a Project “Helios” Conference folder in “Box I: 63”, the Library of Congress has a load of material:

http://memory.loc.gov/service/mss/eadxmlmss/eadpdfmss/1998/ms998008.pdf

Charles Moore (in the Roswell Report) refers to Piccard as “Jean Get”, and says that General Mills were originally making balloons out of pliofilm, which “just went to hell when exposed to sunlight”

https://media.defense.gov/2010/Dec/01/2001329893/-1/-1/0/roswell-2.pdf

General Mills Co., White Plains NY were responsible for most of our C rats in the sixties. I appreciate now how their pliofilm balloons would’ve gone to hell when exposed to sunlight. Our guts turned to mush on a forced diet of their GI ham & lima beans, turkey loaf, ham & eggs etc., which we’d leave on the J trails to bait any Charlie hungry enough to eat the shit. Didn’t work of course, they’d ample supplies of nuoc mam and cadged Aust. Red Cross ‘Big Sister Mushies in butter sauce’ to sustain them until our inglorious RTA in ’72.

What about operation Sea Spray? Some sources (e.g. https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/serratia-marcescens-bacteria-holy-statues-bleed/ ) report that the U.S. Navy sprayed microbes over the S. Francisco Bay, using balloons. Details are scarce, though.

Some more useful links:

http://www.theaerodrome.com/forum/archive/index.php/t-53769.html

http://stratocat.com.ar/stratopedia/200.htm

“The HELIOS flight would carry onboard two passengers: a Navy pilot and a scientific observer. The Navy selected Lt. Harris F. Smith as the pilot for the first mission.”

https://www.airspacemag.com/flight-today/one-balloon-bomber-slightly-used-2162519/

Nick: Captain Malcolm Ross brings back memories of days when names like Gagarin and Glen were all the rage. Of course us old enough will recall his most memorable balloon flight with Vic Prather on 4/5/61 to test the new Goodrich Mk V neopreme suit used by Alan Shepard on his first space voyage (project Mercury ) the very next day. The navy balloonists lifted off from USS Antietam C36 in the Gulf of Mexico aboard their 100 foot diameter open air Gondola balloon and the 10 hours aloft got them to a height of 113,740 feet (still a record). Although all went as planned, the landing was compromised by ship’s extraction crew and whilst Ross was retrieved safely, poor Vic Prather drowned in his pressure suit. Not to worry though, Pres. Kennedy presented his missus with the coveted Harmon medal and a Navy DFC to compensate her loss; so there you go all’s well that ends well.