I’ve been reading up on the pre-history of the telescope recently (hence my reviews of Eileen Reeves’ Galileo’s Glassworks and Albert van Helden’s The Invention of the Telescope), but have omitted to mention why I thought this might be of relevance to the Voynich Manuscript.

The answer relates to Richard SantaColoma’s article in Renaissance Magazine #53 (March 2007) with the title “The Voynich Manuscript: Drebbel’s Lost Notebook?”, which claimed to find a persuasive familial similarity between the curious jars arranged vertically in the pharma sections and Renaissance microscopes, specifically those described or designed by Cornelius Drebbel. His (updated) research also appears here.

The biggest problem with Voynich hypotheses is that, given 200+ pages of interesting stuff, it is comparatively easy to dig up historical evidence that appears to show some kind of correlation. In the case SantaColoma’s webpage, this category covers the stars, the hands, braids, caps, colours, four elements, Francis Bacon’s New Atlantis and handwriting matches suggested: none of these is causative, and the level of correlation is really quite low. All of which is still perfectly OK, as these parallels are only presented as suggestive evidence, not as any kind of direct proof.

It is also tempting to use a given hypothesis to try to support itself: in the 1920s, William Romaine Newbold famously did this with his own circular hypothesis, where he said that the only way that the manuscript’s microscopic cipher could have been written was with the aid of a microscope, ergo Roger Bacon must have invented the microscope. All false, of course. Into this second category falls the “cheese mold”, “diatoms” and “cilia” of SantaColoma’s webpage: if these are to used as definitive proof of the presence of microscopy in the VMs, the level of correlation would need to be substantially higher. But these parallels are, once again, only presented as suggestive evidence, not proof.

Strip all these away, and you’re still left with the real meat of SantaColoma’s case: a set of striking similarities between 17th century microscopes and the curious devices in the Voynich Manuscript’s pharma section. Even if (as I do) you doubt that all the colouring on the pages was original (and upon which some of SantaColoma’s argument seems to rest), it’s an interesting observation.

Having said that, no actual proof or means of proof (or disproof) is offered: it is just a set of observations, resting upon a relatively little-tested tranche of history, that of the microscope. Can we do better? I think we can.

Firstly, modern telescope historians (I’m thinking of Albert van Helden here, though he is far from alone in this respect) now seem somewhat dubious of the various Janssen family claims: and so I’m far from comfortable with placing the likely birth of the microscope with the Janssens in 1590. As Richard SantaColoma points out, Cornelius Drebbel is definitely one of the earliest documented microscope makers (from perhaps a little earlier than 1620, but probably not much before 1612, I would guess).

Secondly, it is likely that the power of the lenses available for spectacles pre-1600 was not great: Albert van Helden calculated that a telescope made to della Porta’s (admittedly cryptic) specification could only have given a magnification of around 2x, which would be no more than a telescopic toy. I would somewhat surprised if microscopes constructed from the same basic components had significantly higher magnification.

Thirdly, the claimed presence of knurled edges in the VMs’ images would only make sense if used in conjunction with a fine screwthread, to enable the vertical position of an element along the optical axis to be varied: but I’m not sure when these were invented or adapted for microscopes.

All in all, I would assert that if what is being depicted in the VMs’ pharma section is indeed microscopes from the same family as were built by Drebbel from (say) 1610 onwards, there would seem no obvious grounds for dating this to significantly earlier than 1610: even if it all came directly from Della Porta, around 1589 would seem to be the earliest tenable date.

The problem is that there is plenty of art historical data which places the VMs circa 1450-1500: and a century-long leap would seem to be hard to support without more definitive evidence.

As always, there are plenty of Plan B hypotheses, each of which has its own unresolved issues:-

(a) they are microscropes/telescopes, but from an unknown 16th century inventor/tradition

(b) they are microscropes/telescopes, but from an unknown 15th century inventor/tradition

(c) they’re not microscopes/telescopes, they just happen to look a bit like them

(d) they’re not microscopes/telescopes, but were later emended/coloured to look like them

(e) it’s all a Dee/Kelley hoax (John Dee was Thomas Digges’ guardian from the age of 13)

Despite everything I’ve read about the early history of the telescope and microscope, I really don’t think that we currently can resolve this whole issue (and certainly not with the degree of certainty that Richard SantaColoma suggests). The jury remains out.

But I can offer some observations based on what is in the Voynich Manuscript itself, and this might cast some light on the matter for those who are interested.

(1) The two pharma quires seem to be out of order: if you treat the ornate jars as part of a visual sequence, it seems probable that Q19 (Quire 19) originally came immediately before Q17 in the original binding.

(2) The same distinctive square “filler” motif appears in the astronomical section (f67r1, f67r2, f67v1), the zodiac section (Pisces, light Aries), the nine rosette page (central rosette), and in a band across the fifth ornate jar in Q19. This points not only to their sharing the same scribe, but also to a single (possibly even improvised) construction/design process: that is, the whole pharma section is not simply a tacked-on addition, it is an integral part of the manuscript.

(3) Some paint on the pharma jars appear original: but most seems to be a later addition. For example: on f99v, I could quite accept that the palette of (now-faded) paints used to colour in the plants and roots was original (and I would predict that a spectroscopic or Raman analysis would indicate that this was probably comprised solely of plant-based organic paints), which would be consistent with the faded original paint on the roots of f2v. However, I would think that the bolder (and, frankly, a little uglier) paints used on the same page were not original.

Put all these tiny fragments together, and I think this throws doubt on one key part of SantaColoma’s visual argument. He claims that the parallel hatching inside the ornate jar at the top of f88r (the very first jar in Q17) is a direct indication that it is a lens we are looking at, fixed within a vertical optical structure. However, if you place Q19 before Q17 (as I believe the original order to have been), then a different story emerges. The ten jars immediately before f88v (ie at the end of Q19) all have vertical parallel hatching inside their tops, none of which looks at all like the subtle lens-like shading to which SantaColoma is referring. For reference, I’ve reproduced the tops of the last four jars below, with the final two heavily image-enhanced to remove the heavy (I think later) overpainting that has obscured much of the finer detail.

This is the “mouth” of the top jar on f102r: the vertical parallel hatching seems to depict the back wall of a jar, ending in a pool of faintly-coloured yellow liquid (probably the original paint).

This is the “mouth” of the top jar on f102r: the vertical parallel hatching seems to depict the back wall of a jar, ending in a pool of faintly-coloured yellow liquid (probably the original paint).

This is the mouth of the bottom jar on f102r, which appears to have vertical parallel hatching right down, as though the jar is empty near the top (or perhaps its contents are clear).

This is the mouth of the bottom jar on f102r, which appears to have vertical parallel hatching right down, as though the jar is empty near the top (or perhaps its contents are clear).

This is the top jar on 102v, enhanced to remove the paint. I think some vertical hatching is still visible there: it would take a closer examination to determine what was originally drawn there.

This is the bottom jar on f102v, again heavily enhanced to remove paint. Vertical hatching of some sort is visible.

This is the bottom jar on f102v, again heavily enhanced to remove paint. Vertical hatching of some sort is visible.

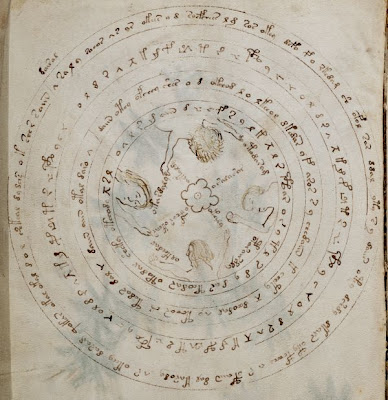

Voynich Manuscript, page f57v (the ‘magic circle’ page)

Voynich Manuscript, page f57v (the ‘magic circle’ page)