Here’s a vogue-ish detail from the Voynich Manuscript – the (claimed) “armadillo” in the middle-left margin on page f80v. Of course, if this can be proven to be intentionally depicting an animal from the New World, then a lot of other dating evidence becomes secondary. But of course, this kind of controversy is nothing new: you only have to think of the decades-long hoo-ha over the (claimed) New World sunflowers.

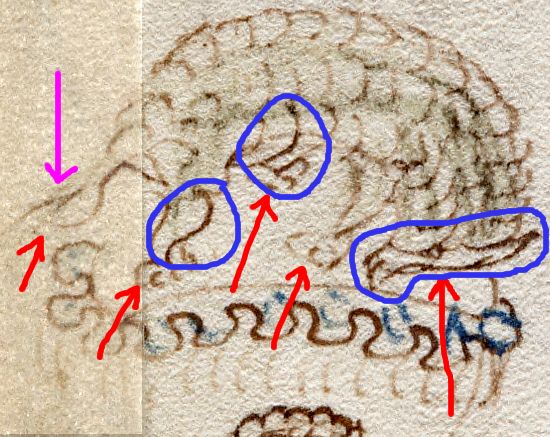

Armadillo proponents “read” this image as having a tail (on the left), three legs (with the left foreleg therefore tucked behind the head on the right), and a kind of upside-down armoured armadillo head facing backwards (with a sort of smiley cartoon mouth). Fair enough.

By way of contrast, I argue that because everything else in Quire 13 appears to be water-related (plumbing, baths, steam, rainbow, pools, etc), this is probably a depiction of a catoblepas – a fearsome creature Leonardo da Vinci (and doubtless many of his contemporaries) believed lived at the source of the Niger river, and whose bull-like head was so heavy that it permanently hung down to near the ground.

Specifically: what appears to the pro-armadillo contingent to be a tail (purple arrow), I read as a left rear leg, making all four legs visible – and what they read as an armoured armadillo head, I read as a pair of bull-like flat horns at the back of a down-turned head.

All the same, it’s not like I can’t ‘see’ the armadillo: it’s a lot like one of those optical illusions (such as the famous old lady / young girl drawing) where you can flip between two parallel readings almost at will.

But the odd thing here is that both the armadillo and the catoblepas might be equally correct. It doesn’t take a great deal of sophisticated codicology to look at the line strengths (in the areas ringed blue above) and note that a few key lines are in a darker ink, quite different from the ink used for the wolkenband-like decoration just below it. Could it simply be that some 17th century owner (for whom the catoblepas was probably never part of their conceptual landscape) thought this picture somehow resembled an armadillo, and emended it to strengthen that resemblance? I think that this is very probably precisely what happened here.

Now, this is precisely the kind of contingent, layered, conjectural historical explanation (basically, an intellectual history of art) that Richard SantaColoma has long enjoyed lambasting. Specifically, he sees any explanation that appeals to layered codicology as fully worthy of his scorn – as though it’s merely constructed as an apologium to keep the faith with the existing ‘mainstream’ dating evidence.

But actually, layered codicology hypotheses are among the most brutally (and easily) testable of historical ideas – unless two layers of ink added many decades apart just happened to use exactly the same raw materials (and in the same proportions), we will ultimately be able to differentiate them… or not.

However, unless people explicitly propose such layering hypotheses, nobody would think to do such tests – they’d perhaps spend all their codicological efforts on f116v (a valid investment, to be sure, but it’s only one of many possible areas of the Voynich Manuscript that should be tested for revealing information).

Indeed, the whole point of such historical hypotheses is not to prove historical narratives in and of themselves, but rather to lay the underlying ideas open to physical mechanisms of disproof. Bluntly put, any given hypothesis is usually of little or no value if it cannot be specifically disproved (because direct causative proof is as rare as hen’s teeth in history).

In the absence of any suitable tests on f80v, however, both viewpoints (and indeed all other fairly sensible viewpoints) remain in a suspended state of vague possibility, hypothetical kites floated carelessly into an unthreatening breeze.

Hmmm… how I long for such tests!