Once upon a time in America, a child maths prodigy at Harvard (taught by famed logician W.V.O.Quine, no less!) volunteered as a guinea pig for Project MKULtra. This involved a long-term series of personality stress tests – specifically, experiments in torture, coercion, mind control and vivid psychological abuse. (All participants had codenames, I read that his was “LAWFUL”).

Less than a decade later, that same now-former child prodigy grew increasingly disenchanted with the industrial world; gave up his professorial post; dropped out of mainstream society, moving to a remote cabin outside Lincoln, Montana; and between 1978 and 1995 sent at least 16 mail bombs to universities and airlines. The FBI dubbed him “UNABOM” (“UNiversity & Airline BOMber”), but the media rechristened him the “Unabomber“. After getting his manifesto “Industrial Society and Its Future” published in The New York Times and The Washington Post (under threat of more bomb attacks), the Unabomber – Ted Kaczynski – was finally identified and arrested in 1996. Though he avoided the death penalty, he will remain in prison for the rest of his life.

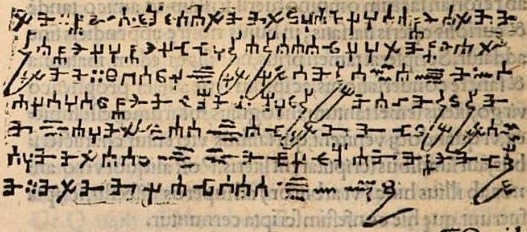

What’s relevant for us is that Kaczynski filled his notebooks with a mixture of English, Spanish and a numeric cipher (as a maths professor, naturally he would use numbers to hide his secrets). Helpfully, investigators found the key to the cipher amongst his papers (many of which were later sold at auction), though this seems to have taken the FBI a whole decade to crack (yes, even with the key).

This was a story which Bruce Schneier picked up on in 2006 and then in early 2007, when he had been shown some (but far from all) cryptanalytical notes as to how Kaczynski’s complicated cipher system worked. On his blog, Schneier posted links to three pages he believed were original (and to two other pages he thought had probably been originated by an FBI cryptanalyst), though unfortunately all of these images have since disappeared from both the web and the Wayback Machine (while Schneier himself didn’t keep copies, he told me yesterday).

The only problem is that I don’t (yet) completely believe the story as reported is entirely correct – because the cryptography as described just doesn’t seem (to me) to link up with the ciphertexts in the way that it should.

Firstly, [which I found thanks to this 2003 Zodiac Killer forum page], the original Unabomber trial news reports described how “FBI cryptographer Michael Birch” used the notes that had been found in Kaczynski’s cabin to decipher his notebooks.

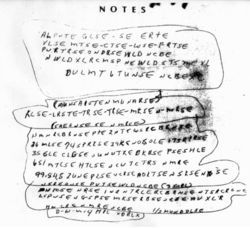

The diary, written in pencil on several hundred pages of notepaper and several inches thick, includes details of experiments with explosives. It was among 20,000 documents seized from Kaczynski’s tiny Montana shack.

The diary contents have not been made public, although Birch’s decoded version was given to the defense last year.

Sources familiar with the journal describe it as a sophisticated jumble of numbers, an intricate enigma wrapped in a riddle befitting a Harvard-trained mathematician described by one prospective juror as a “smart weirdo.”

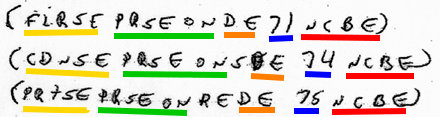

Back in 2003, Douglas Oswell posted a grainy scan of a 42×52 cipher grid sheet that the FBI had released, where the top line seems to be “4 7 7 0 1 3 81 …”. This seems to have been taken from a book called “Harvard and the Unabomber” by Alston Chase. As I understand it, Chase included a list of numeric cipher key equivalents running from 0 (“for”) up to 89 (“delete”), all of which Oswell transcribed and placed online here. However, that numeric key does not seem to match up to the data in the grids, leading people to surmise (rightly) that there was at least one more enciphering / deciphering step involved.

I also found an image of a cipher grid codesheet that had been auctioned, where the top line is “… 7 54 4 2 13 1 72 11 7 36 18 1 5 6 4 12 15 29 27 30 29 47 8 37 75 8 45 41 19 2 21 13 34 2 …”. Though this has diagonal lines marked in (more on that later) and is at least 36 columns wide, the number sequences listed seem to me to employ a subtly different enciphering scheme to the image given by Alston Chase (though I might well be wrong).

Finally, the 2007 KPIX news report to which Bruce Schneier contributed (and which you can see on YouTube) describes a multi-stage horizontal, vertical, and diagonal “unscrambling sequence” (which could only ever work on numbers laid rigidly out on a grid), followed by a “marrying” and/or “merging” stage (combining pairs or groups numbers to yield more meaningful numbers). The report showed long non-gridded lists of numeric ciphers, such as…

73,32,51,91,62,59,33,13,15,11,57,31,7,…

33,82,30,76,31,53,42,35,6,24,51,61,1,75,…

16,41,95,87,91,55,62,51.

96,15,93,32,25,85,44,22,72,36,94,96,…

54,72,15,89,52,87,21,66,72,26,89,51,90,…

…and…

40,44,73,33,10,60,11,48,59,98,47,23,…

82,31,35,19,17,37,13,6,27,94,31,15,3,…

9,18,39,55,61,12,50,13,99,91,83,61,7,…

69,68,21,34,59,25,42,75,80,91,16,35,48,…

5,42,68,9,40,6,17,97,86,71,71,2,81,55,60,…

50,49,78,62,52,57,25,36,34,80,…

15,77,3,81,2,35,86,22,4,8,21,73,7,…

21,47,57,1,99,7,85,44,13,5,67,84,…

12,96,58,19,47,32,18,34,26,96,15,…

83,88,41,44,59,76,10,55,18,30,44,…

Yet only part of the back-end numeric cipher key is apparently given in the report:-

82 = SO

83 = ST

84 = TH

85 = THAT

86 = THE

87 = THERE

88 = THEN

89 = THIS

90 = TO

91 = TR

92 = UN

93 = UNDER

94 = UP

95 = WHAT

96 = WHEN

97 = WHERE

98 = WHO

99 = WH[Y?]

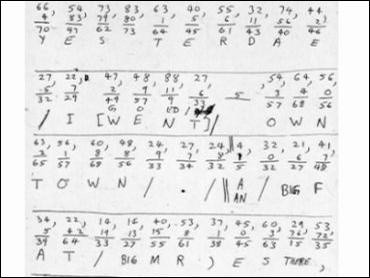

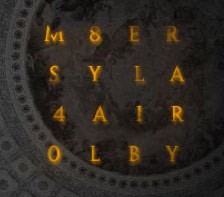

A worksheet was also released, that looks like this:-

This pre-back-end-numeric-cipher calculations seem to involve adding pairs of numbers together (where if the tens column overflows into the hundreds column, that overflow gets added back into the tens column), and then using the final output pair of digits as an index into a table of letters or tokens similar (but not identical) to the one originally given by Alston Chase, i.e.

66 + 4 = 70 –> Y [Chase gives ‘X’]

54 + 83 = 137 –> 47 –> E [same as Chase]

73 + 79 = 152 –> 62 –> S [same as Chase]

83 + 80 = 163 –> 73 –> (null) [Chase gives ‘delete’ (‘null’?)]

63 + 1 = 64 –> T [same as Chase]

etc.

So, an open-and-shut case? Well… no, not really. Here’s what I don’t understand:-

* Why did the FBI say that it could read the cipher notebooks in 1996, when it then claimed to have cracked them only in 2006?

* Why does the numeric key given in Alston Chase’s book differ so radically from the one (82-99 only) shown by KPIX?

* Did Kaczynski use multiple numeric cipher keys?

* Why did the KPIX news report show lists of comma-delimited numbers as the contents of the notebooks if the method used to unscramble the sequences only worked on rigidly laid out cipher grids?

* Why was the numeric key given in Alston Chase’s book subtly different from the one used in the worked “YESTERDAE” example?

Don’t get me wrong, I’m really not doing anything like advocating Ted Kaczynski’s innocence or somehow endorsing his anti-industrial position etc. Rather, even though I’ve looked carefully at all the cryptographic evidence I’ve been able to find, I just don’t see how it’s supposed to hang together as a consistent piece of cryptological data.

Could it have been… that the original decryption involved not simply “learning how to apply the code to the defendant’s coded writings and the admission into evidence of [Birch’s] completed translation” (as claimed), but also having to infer the 100-letter numeric cipher alphabet that was perhaps not included in the “unscrambling sequence” notes? Could it be that the FBI was overanxious to paint a pre-trial picture convincing to jurors that what they had was ‘simply’ an an unambiguous “translation” rather than a (possibly interpretative) “decryption”?

This was, after all, really not long at all after FBI whistleblower Frederic Whitehurst had famously made his numerous allegations of forensic mishandling inside the FBI’s Laboratories, causing (for example) much of the explosive analyses done on the Unabomber case to be considered too unreliable to be used in court. If the ciphered journal was to be, as lead prosecutor Robert Cleary described it, “the backbone of the government’s case”, then there surely must have been internal political pressure for it to have been presented as if it were utterly rock solid evidence,

However, from the subtle difference between the numeric cipher given by Alston Chase and the one (implicitly) presented in the worksheet, I suspect that the FBI’s cryptanalysts didn’t manage to completely lock down the numeric cipher key list in 1996. Helpfully, Kaczynski seems to have made the decryption a little easier by using many letter keys in alphabetical order (a mistake people have made with numeric ciphers for centuries), and hence the decryption as presented to the jury was very probably extremely close to what Kaczynski had written. But if it wasn’t 100%, I don’t personally think it should have been presented as a “translation”.

So, if you’re like me, you’d now like to know a little more about the key to the Unabomber’s cipher journal that was found in his cabin. But given it’s the FBI (and many of the Unabomber records are locked for the next 50+ years), perhaps we won’t. Hopefully we shall see sooner than that… fingers crossed!