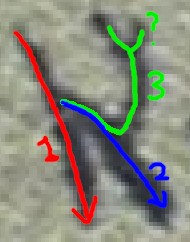

Carrying on with the Somerton Man Melbourne nitkeeper research thread, here’s a timeline I’ve reconstructed for the (in)famous baccarat school that Christos Paizes (AKA “Harry Carillo”) and Gerald Francis Regan ran on the first floor above the Old Canton Cafe at 158 Swanston Street, Melbourne. (Swanston St runs between Lonsdale St and Little Lonsdale St.)

Note that as of 21 Jun 1943, 158 Swanston St was advertising for a “Pantry Maid” (“over 45; £3 10/ p. wk., no night work“), so presumably the building was still in use as a cafe at that date.

Phase 1 – Baccarat still legal

Because Victoria’s gaming laws had been drafted by listing specific games that were deemed to be illegal (e.g. the Aussie favourite two-up), Melbourne police needed overwhelming physical proof in order to prosecute anyone playing a game not on the prohibited list.

As a result, this first phase of the timeline sees the police very much on the back foot. What’s more, none of the cunning stunts they used to try to gain evidence against the baccarat schools impressed the courts. For example:

16 July 1942: The Truth’s influential 18 Jun 1944 exposé (it was mentioned in Hansard) discussed how police attempts to prosecute Regan & Carello in their baccarat school in Flinders St in 1942 had miserably failed:

[…] a charge at the Petty Sessions of acting in the conduct of a common gaming house at 510 Flinders Street, was withdrawn. On that occasion, police watched a baccarat game through holes in the ceiling, but they obtained no evidence that percentages were deducted from the winnings — an all-important point in law.

By 1943, the police started to find ways of prosecuting individuals involved with these gaming schools. One target was the nitpickers (or “cockatoos”), whose job was to raise the alarm when a police raid was in progress, and who could be charged with ‘hindering’ or ‘obstruction’:

[Gerald Francis Regan] was convicted for obstructing the police, when they entered a gaming house.

By June 1944, the Melbourne baccarat scene was (as per The Truth’s exposé) well and truly flourishing: there seemed almost nothing that the police could do about it. For all The Truth’s thundering, you can’t help but notice that they did helpfully include the exact address to take your money to:

At Stokes’ schools, the game is big, but if it is a bit severe on the pocket, you can be accommodated at Regan and Carello’s school, on the first floor of a building at 158 Swanston St. You won’t like it much here, because you will find a definitely low type crowd, mostly Italians, Greeks and European refugees. In the crowd of 100, there will be about 20 women.

Phase 2 – Baccarat Made Illegal

Perhaps surprisingly, The Truth’s moralistic tabloid ranting against the baccarat schools (which incidentally made the gangsters running them so livid that they offered £500 for the identity of the person who had given the paper the inside story on both Stokes’ school and Paizes’ school) stirred up enough Victorian political indignation to change the law.

Hence from 1st July 1944, baccarat found itself added to the list of games that were illegal to play in Victoria: which meant that the police were able to steam in, door-bashing sledgehammer in hand, confident that the gaming law was (at last) on their side.

The moment this became law (1am on 1 Jul 1944), raid on a Swanston Street baccarat school led (in the Third City Court in August 1944) to a group of baccarat players being fined under the newly extended gaming laws:

When police broke into a baccarat school in Swanston-street with a sledge hammer early this morning, they found a “League of Nations Assembly” around the table.

Among the 40 players— 17 of them women— were Russians, Poles, Italians, Lebanese, Albanians, Syrians and Britons. Three men were fined £3 because they had prior convictions: the remainder £2.

Fety Murat, 33, of Drummond-street, Carlton, waiter, who had charge of the game, was fined £50. It was the first raid since legislation was passed to make baccarat illegal.

(Note that a different report gave the address as “303 Swanston St”, but perhaps 158 was the downstairs address, and 303 the upstairs address.)

Phase 3 – Shutting Down the School

Over the next year, the next phase of the police operation involved building up (what they hoped would be) a sufficiently strong case to convince the courts to close down the Old Canton Cafe baccarat school for good.

On 19 July 1945, Mr Justice Lowe at the Practice Court received the following:

An affidavit by Sub-Inspector Abley, officer in charge of the gaming police, stated that police officers had seen baccarat played on the premises. The police had visited the premises almost every night for approximately six months. The only means of access was a narrow stairway, having doors both at the top and bottom. There was a person always on guard at the top of the stairway to ensure that the police could not enter without warning. For four months, said the affidavit, the premises had been run ostensibly as a club. On many occasions the police entered the premises after a short delay, and saw people scattering from a table suitable for baccarat. After quoting various matters in his affidavit, Sub-Inspector Abley said he had reasonable grounds for suspecting that baccarat was carried on, and that the premises constituted a common gaming house.

According to a different report, the affidavit further asserted that…

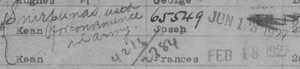

[…] the persons having the control and management were Christos Paizes (alias Harry Carillo), William John Elkins, Gerald Francis Regan and Richard Thomas (alias Abishara) and a man known as Balutz.

Christos Paizes responded with his own affidavit:

[…] Christos Paizes, of Mathoura-road; Toorak, stated that, with Gerald Francis Regan, of High-street, St. Kilda, he had been the tenant of part of the first floor of the building in Swanston-street, known as the Old Canton Cafe. Since they had occupied the premises they had never been used as a common gaming house. Until January, 1945, they conducted the premises as a cafe and lounge. Since then they had conducted the premises as a proprietary club. In the club refreshments were supplied to members, who used the premises to play various games of cards and checkers, but no unlawful games were permitted on the premises. With the exception of the addition of one door on the stairway, the premises were in the same condition as when first occupied by them.

Moreover (as you’d expect), Paizes utterly denied having a nitkeeper:

Paizes denied the various allegations made in Sub-Inspector Abley’s affidavit, and said it was not true there was anyone on guard to ensure that police officers did not enter without warning.

However, Mr Justice Lowe judged that what was being run above the Old Canton Cafe was indeed a gaming house:

An order declaring that the premises formerly known as the Old Canton Cafe, Swanston-street, Melbourne, and being that portion of the first floor of the building leased by Christos Paizes were a common gaming house, was made by Mr. Justice Lowe in the Practice Court yesterday. His Honor stated that the order would take effect as from Wednesday, August 1.

And so notice was served on the premises: which effectively marked the end of Melbourne’s Golden Age of baccarat schools. Which is not to say that baccarat suddenly stopped (because it most certainly did not): rather, it was that baccarat’s gilded era had finished, and it became just a low-life activity.

A Dissenting View

Oddly, “Gangland Melbourne” (which, though lively, often seems to me to get stuff wrong) asserts that Harry Stokes (prior to his death in 1945) had (p.81):

“teamed up with Gerald Francis (‘Frank’) Regan and Lou the Lombard running games at the Canton cafe in Swanston Street. Opposed to them were Kim Lenfield, Charlie Carlton, Hymie Bayer and Abe Trunley at the Ace of Clubs, Elizabeth Street. Ralph Pring of the VRC financed the Kim Syndicate, which also ran games at 52 Collins Street. The old-time confidence man Harry ‘Dictionary Harry’ Harrison […] had also returned to Melbourne and become involved in the baccarat schools.”

Lou the Lombard would pop up again in 1951 in “Gangland Australia” (p.131), running a baccarat game “on the corner of Elizabeth Street and Flinders Lane”. But apart from that slightly circular reference, everything else in the above account seems a bit free-floating (as you’ll find if you try searching any of the names in Trove, apart from Dictionary Harry).

So, did The Truth completely misread the baccarat school ‘scene’? Or might the Gangland Melbourne authors have been given dud information? (I suspect the latter, but I thought I ought to mention the former.)

Alternatively, if you know of a book (say, a Melbourne police memoir?) that covers this period of time a little more reliably, please say! (And yes, I’ve read Robert Walker’s serialised memoirs, but thanks for asking.)

Phase 4 – Life After Baccarat

In April 1950, we see Richard Thomas (AKA Abishara, but now manager of the Copacabana Restaurant in Collins Street), Christos Paizes (a shareholder in the Copacabana) and Feti Murat (now a “market gardener”) in a brawl with undercover policemen in Swanston Street. “Murat, who described himself as a market gardener, said he had worked for Paizes some years ago.“

As for William John Elkins, it seems he was born in 1911; in 1938, he was “charged with having had the care and management of a gaming house”; in 1941, we can see him resisting extradition from Fitzroy to Adelaide in connection with a stolen radio; he died in 1964.

So, once again it seems that the only major player we cannot trace beyond 1944 is the mysterious Balutz.

Who Were The Two Gamblers?

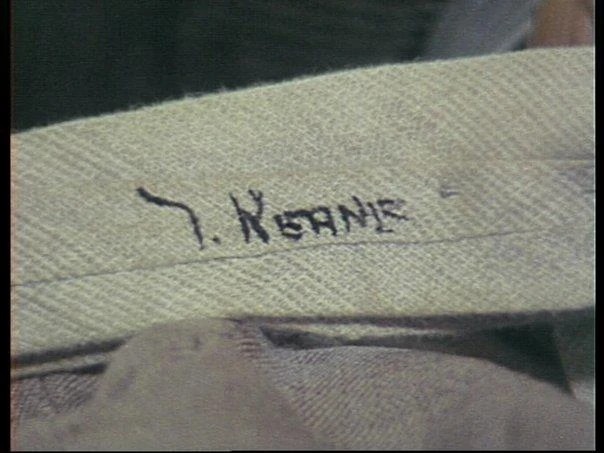

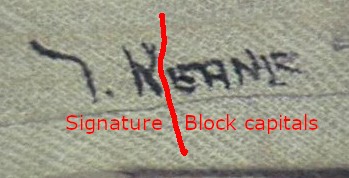

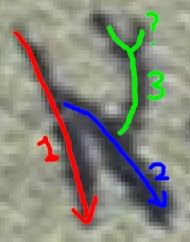

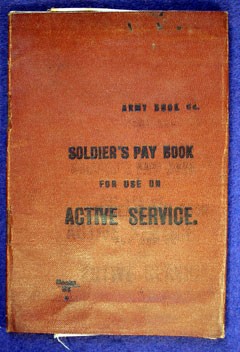

If you recall, the Somerton Man was tentatively identified in 1949 as a nitkeeper:

Two promininent Melbourne baccarat players who desire to remain anonymous, believe they knew the unknown man in the “Somerton beach body mystery.”

They saw the man’s picture in a Melbourne newspaper and said they thought they recognised him as a “nitkeeper” who worked at a Lonsdale street baccarat school about four years ago. They could not recall his name.

They said the man talked to few people. He was employed at the baccarat school for about 10 weeks, then left without saying why or where he was going.

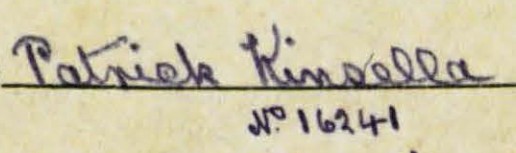

But who might these “two prominent Melbourne baccarat players” have been? Trawling through all the stories in Trove (particularly from The Truth) has thrown up various prominent baccarat player names (of course, Christos Paizes himself started as a gambler), such as:

- super-gambler (and super-litigant) Michael Pitt (who hated the press)

- James Coates (‘The Mark Foy’, murdered in 1947 so we can rule him out)

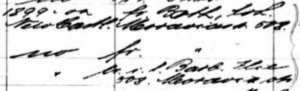

My favourite baccarat gambler news story from the period was from 18 Dec 1946, relating to a loan made on 15 Jun 1945 between two baccarat players (“Charles [Albert] Darley, outdoor salesman, of St. Kilda” [and] “Eric Allen Kermode, assistant manager of a poultry business in Camberwell“) at a baccarat school at the Canton Cafe. (The case was dismissed with costs.)

To be honest, though, unless the descendants of a 1940s baccarat player step forward to recount the hoary old Somerton Man nitkeeper camp-fire tale their (grand-)father used to tell them, this detail is probably lost to history.

Where To Look Now?

There’s no shortage of police activity documented here: six months of active surveillance on a single site would have involved amassing dossiers on every baccarat school principal, so a ton of paperwork must have been generated. But what happened to that? Can all of it simply have been lost?

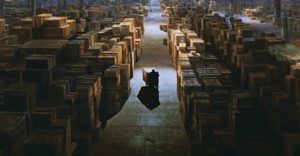

There is little doubt in my mind that Victoria Police’s Archive Services Centre – dubbed the “Bermuda Triangle of police files” – contains everything we would like to know.

[…] 135,000 boxes packed floor to ceiling in a cop version of a Costco.

More than one-third have not been catalogued, and records are rudimentary at best for many others.

“It’s a rabbit warren. Police keep almost everything and it’s an organisational nightmare down there,” a former senior police commander says.

Hence it seems to me to be a reasonably safe bet that it is in there, right next to the box containing the Ark of the Covenant. Here’s hoping!